Is it possible to clone a dinosaur? Or could we bring back dinosaurs some other way? We ask because it’s the 30th anniversary of Jurassic Park, and we’ve got dinosaurs on the brain.

In the lead-up, we decided to dive into the world of animal cloning and dinosaur husbandry by speaking to researcher Dr Susie Maidment of London’s Natural History Museum and Ben Lamm, founder and CEO at Colossal Biosciences, who are trying to “de-extinct” the dodo and woolly mammoth among other creatures. Recorded as part of The Big Questions, IFLScience’s podcast, we cover how far cloning technology has come, some flaws in the logic of Jurassic Park, and why dino dentistry is going to have to become a thing if we bring back the dinosaurs.

What do we know so far about the possibility of bringing dinosaurs back?

Dr Susie Maidement: Well, people have had some ideas about how we might be able to bring dinosaurs back. The first one in Jurassic Park was the idea that we could maybe extract some blood from a mosquito and then take the DNA from that to fill in the gaps in “dino DNA”, and then clone a dinosaur. Well, we still can’t do that 30 years on from the film, and that’s because we haven’t found any DNA from dinosaurs.

In fact, the oldest DNA in the fossil record is probably only around a million years old, maybe a bit more. The dinosaurs died out 66 million years ago, so definitely we don’t have any DNA for dinosaurs at this point. We do, however, now have some blood, so we have some red blood cells that are preserved from dinosaurs and some other soft tissue features. So maybe in the future we might be able to get some DNA.

There are a couple of other different techniques that are going on though. One of those is reverse engineering, which is this idea that you could take birds, which are the direct descendants of the dinosaurs, fiddle around with their genetics, and produce something like a dinosaur.

When you’re talking about the precious dino DNA there, in Jurassic Park they use a mosquito trapped in amber. Could that be a source?

SM: When we look at insects in amber, what we tend to find is the outside of the insect, the chitinous husk – or the crunchy bit, if you like – of the insect, but the inside stuff isn’t preserved. So, there isn’t any blood found within those. But there has been a beautiful specimen of a mosquito found preserved in lake sediment. So, these are very finely laminated, finely layered sediments, and this specimen had a dark stain around its abdomen.

When they tested that, they actually found the breakdown products of haemoglobin. So, it was blood in a mosquito’s abdomen, however, that specimen was only 60 million years old, so not old enough to be around at the same time as the dinosaurs.

A massive gap, then, between where we’re at now and where we need to get to. In the movie, when they extract the DNA from the amber specimen, they get this genome but it’s not quite complete, so their idea is “Well, we’ll just get a bit of a frog, and we’ll plug in the gaps.” Could that work?

SM: There are some fairly major flaws with this whole concept. Firstly, in order to know where the gaps in the DNA are, you need to have the whole genome to start off with, otherwise you don’t know which bits are missing.

The second problem is that frogs are the least likely organism you would choose. The organism that you would choose would be birds, because birds are the direct descendants of dinosaurs. When Jurassic Park came out, I don’t think that was 100 percent accepted. There were some ideas that it might be the case, but it wasn’t as widely accepted as it is now.

Now that’s just fact, but they still wouldn’t have used frog. Humans are more closely related to dinosaurs than frogs are. So it was totally a bizarre choice, but it was needed for the narrative of the film. They needed the dinosaurs to be able to change sex randomly and then produce offspring and this is something that some frogs can do.

[Interestingly, since our interview with Maidment research has come out saying that the discovery of parthenogenesis in a crocodile makes it “very likely” that pterosaurs and dinosaurs were also capable of reproducing without sexual reproduction. So, it could be that Jurassic Park would’ve been a total disaster even without that pesky amphibian DNA genome plug.]

Elsewhere in the field of animal cloning, co-founder and CEO of Colossal Biosciences Ben Lamm has been working towards the “de-extinction” of several extinct species. We asked him what exactly that means.

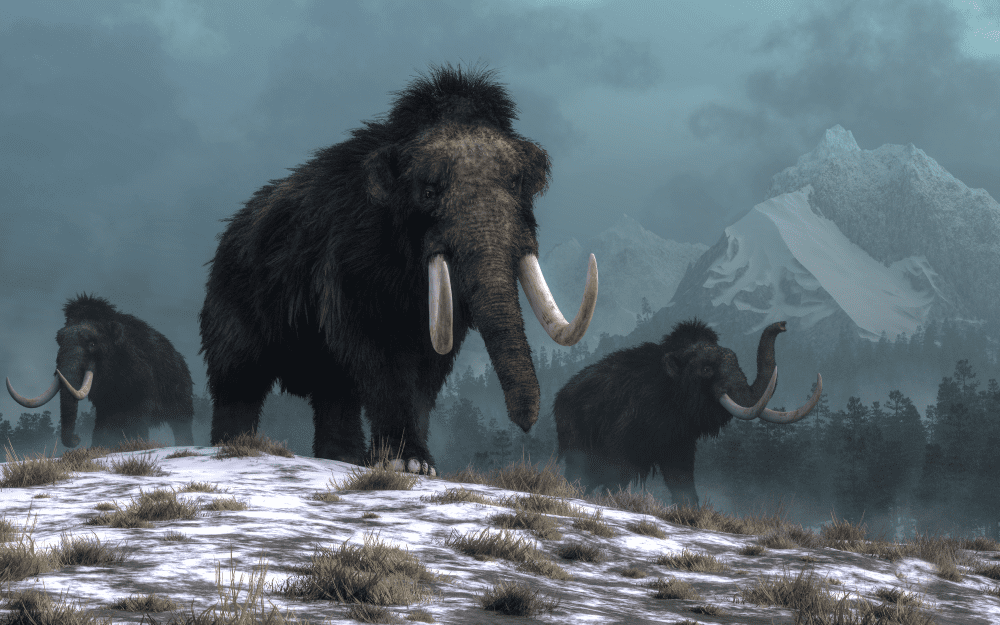

Ben Lamm: Colossal Bioscience is, to our knowledge at least, the world’s first de-extinction and species preservation company. What that means to us is looking at and understanding which genes are associated with the core phenotypes, or physical attributes, that existed in an extinct animal.

For example, for the woolly mammoth, it’s the dome cranium, the curved tusk, and whatever is making it cold-tolerant, as well as a lot of things under the hood. Things like how nerve endings respond to freezing temperatures, how the body produces haemoglobin, and the shaggy wool coat.

What we’re asking is how can we at Colossal understand the core genes that made elephants cold tolerant. Those genes are now extinct, so how do we de-extinct those genes and put them into the architecture, if you will, of an existing living animal? At the moment, that’s the Asian Elephant which is 99.6 percent the same genetically as a woolly mammoth. If we can de-extinct those genes, then you have the mammoth 2.0.

What other species have Colossal got their sights set on for de-extinction?

BL: We’re working on the woolly mammoth, the thylacine, also known as the Tasmanian tiger, and then the iconic dodo from Mauritius.

When you’re working with these different species, what’s the bare minimum you need in terms of biological material to work with?

BL: First you need to look at, what is the closest phylogenetic relative? What is the animal that is still existing on the planet that’s the closest on the family tree? For example, for the woolly mammoth, that’s the Asian Elephant. As I mentioned, it’s 99.6 percent the same, genetically. Most people don’t realize this, but an Asian Elephant is closer genetically on the family tree to the woolly mammoth than it even is an African elephant. You need to find the closes phylogenetic relative because you’ve got to find and build a reference genome, and you need tissue samples to do that.

Then, you’ve got to get tissue samples containing the ancient DNA of those extinct species. Ancient DNA is different from existing living DNA, because it’s massively fragmented. It’s not all exogenous, meaning that there are other microbes and living things that have contaminated it over time. So you get snippets of ancient DNA and then you basically piece them together. With the mammoth, we actually used 54 different mammoth genomes to build our reference genome.

Establishing a mammoth reference genome has been something of a puzzle for scientists at Colossal Biosciences.

Image credit: Daniel Eskridge / Shutterstock.com

Then lastly, you need a surrogate that will be able to house the genetically modified embryo once you get there.

Getting that ancient DNA from tissue samples, does that get harder and harder the further back in evolutionary time that you’re working with?

BL: Yeah. It’s also conditions. So, there are animals that are extinct more recently than mammoths that went extinct in very hot and wet places. That’s not a great place for DNA. Cold, dry places are great. Things like caves or the Arctic, in the case of the permafrost.

The thylacine went extinct in 1936, and people preserved some pups in ethanol for scientific study, so from that we were able to sequence a nearly complete genome. So, it really depends. Sometimes you get lucky, but generally speaking, the further back you go and the hotter, wetter places you are, it gets harder.

Just before we move on to dinosaurs, you mentioned there about species that have gone extinct in more modern times. That’s a really interesting point because your company, beyond the de-extinction of long-lost species, also intends to support conservation projects, right?

BL: All of the technologies that we develop on the path to de-extinction, some of them have applications to human healthcare which we are monetizing. We did that last year, we spun out our first computational biology platform, but all the technologies that could add to assisted reproductive technologies or conservation groups for zoos or animal groups worldwide, we are subsidizing and giving to the world for free.

Those are tools like better semantics on nuclear transfer techniques and better computational biology for research. All the data we built on Asian and African elephants we publish to science so that people can use those. A lot of these technologies can not only be used to bring back mammoths, but can also help critically endangered species.

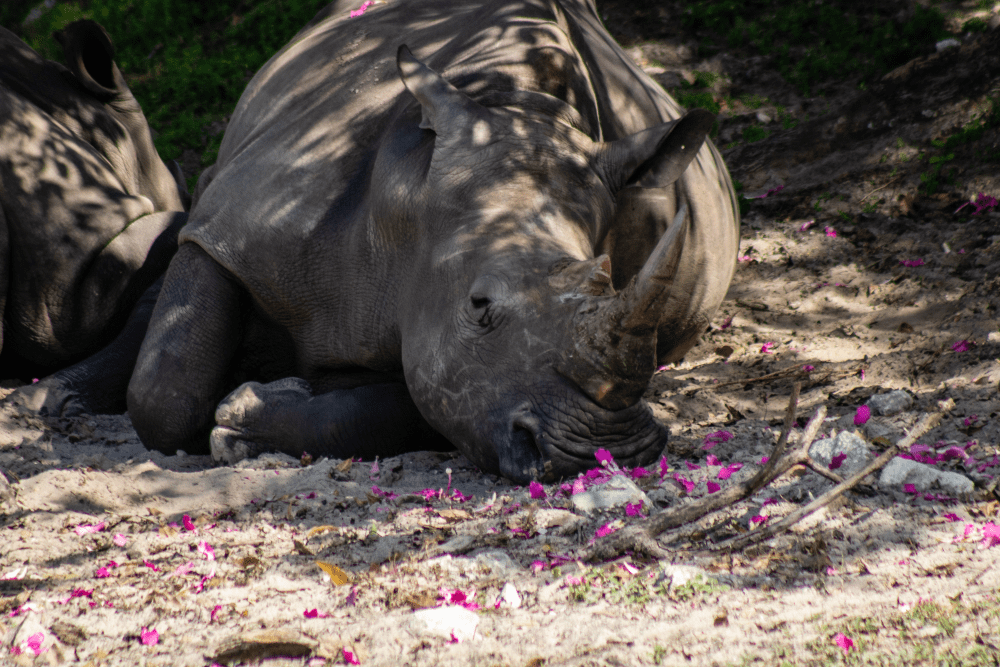

We’re also working towards technologies like artificial wombs – which are a way off, it’s much more likely you will see extinct animals from us before we see artificial wombs – but once we get there, think about what that could mean for species like the Northern white rhino, where there are only two females left.

If we could clone them or create genetically modified versions of them, inserting DNA from other lineages that don’t exist anymore, and you insert that biodiversity, then you can grow them in a lab and work with great re-wilding partners to put them back in the wild. That’s pretty awesome.

Trying to de-extinct the mammoth could help animals like the Northern white rhino.

Image credit: Suzanna Ruby / Shutterstock.com

We think it could be transformative for conservation. So, this de-extinction tool kit that we’re building over time with our species, we want to make available and free for every conservation group out there.

So what if we really let our imaginations run wild, and we did bring back dinosaurs? What happens next? As Dr Maidment explained, animal welfare doesn’t get any easier when you’re dealing with long-extinct species.

SM: There are all sorts of problems here. First of all, the dinosaurs lived for 170 million years on Earth. That’s a really long time. T. rex is actually closer to us in time than it was to Stegosaurus. Many dinosaurs were already fossils by the time other ones lived, so you’re bringing all these different animals together and putting them alongside each other, already that’s weird.

But also, what about the things that they eat? Grass hadn’t evolved when the dinosaurs were around, so the herbivores weren’t eating grass, and grass is quite difficult to eat. It has lots of bits of almost glass-like material in it, which causes your teeth to wear down really, really fast. Horses have evolved these very high crown teeth which wear down over time, but dinosaurs didn’t have that. They replaced their teeth continuously throughout their lives.

If they were eating grass, could they have digested it? Could their teeth replacement rate keep up with being worn away? Would some of these plants today be poisonous for these dinosaurs that lived in a world where flowering plants hadn’t even evolved yet?

I think there is a bit of concern over what they would eat and how they would get on with each other. But of course, what rights would they have today? Would they be treated like living animals? Or because we’ve invented them and reconstructed them, would they have a different status? There are a bunch of ethical concerns around it as well.

Opening up a new era of dino dentistry could be exciting, but it’s probably a difficult sell for modern zoos. However, as Ben told me, we probably don’t need to worry about seeing a living, breathing T. rex any time soon.

BL: We are asked the dinosaur question all the time. People love mammoths, people love dodos, and obviously thylacines too, but people really want dinosaurs. We get probably two or three emails a day about dinosaurs.

I don’t want to break hearts, but it is not possible to de-extinct a dinosaur.

Every so often, you will see some press or paper that’s like, “Oh we got some dino DNA”. Like Ken Lacovara who is arguably the number one palaeontologist in the world that discovered Dreadnoughtus. He’s amazing, he’s one of our scientific advisors, he’s probably been the closest because he’s actually developed a process to de-mineralize dinosaur bones and get basic fragments of amino acids but, you know, we’ve just had amino acids for our mammoth project but we’re not working on it because it’s not possible.

So, it’s not currently scientifically possible to bring back a dinosaur. I do think that the tools over the next 20 years could get us to the point where you could engineer species with dinosaur-like traits. However, unlike our work with the mammoth, we can’t really look at the genome and identify those core genes and de-extinct them, so I don’t think it’s possible to bring back a dinosaur or de-extinct one.

I do think that over time you could probably engineer dinosaur-like things, but I think then you’ve really got to ask yourself why? Why are you doing it? What’s the purpose? How does this help the world? How does this help our ecosystems? How does this help humanity? I think you’ve got to be really thoughtful about it.

Lamm likes T. rex, but isn’t convinced we need to add human-eating predators to our doomsday Bingo cards right now.

Image credit: FABRIZIO CONTE / Shutterstock.com

Bringing back the dinosaurs makes for a great movie, but it’s not necessarily useful science. However, if we were to throw caution and scientific limitations to the wind and just have fun with it, what dinosaur would you most like to see alive?

BL: I would lean towards the T. rex. Once again, I’m not encouraging anyone to work on the T. rex because I think that would be big and scary and terrifying for the world. We already have enough existential problems right now, we don’t need to add T. rexes to our current list of problems. We need to focus on politics and climate change, let’s focus on the existing problems before we introduce new ones.

Over at the Natural History Museum, it seems like the scientific, logistical, and safety concerns around bringing dinosaurs back from the dead have put Dr Maidment off entirely.

SM: Well firstly, did you watch the film? It didn’t end well. So, I’m going to say that maybe it’s not the best idea. I think if I had to choose one, it’s really tricky, because I would say Stegosaurus because it’s what I work on. It’s a dinosaur that I know really well, but then I’d be out of a job, so you know, I don’t know that I’d choose any to be honest with you.

An unexpected answer, but we like it.

Finally, and it’s a question that’s burned in our brains for the past three decades: could a Velociraptor really open a door?

SM: The meat-eating dinosaurs had their hands facing each other, so their palms came together. If you imagine the hand position of clapping and typing, they were clappers. So, their palms couldn’t face the floor.

For most meat-eating dinosaurs, they couldn’t have rotated their wrist round to open a door, their wrists don’t work like ours. Things like Velociraptors had the ability to almost fold their arms backwards like a wing, because this is where wings evolved from in dinosaurs very similar to them. So, they had this bone in their wrist that would have allowed their wrist to fold back, but I’m still not totally convinced that it could have operated a door handle. So, I think we’re safe.

All you need to beat a Velociraptor is to build a door – you heard it here first, folks.

We’ve teased the movie a bit, but the reality is it’s a film that has shaped the lives of many people at IFLScience – our space correspondent Dr Alfredo Carpineti even hosted a 30th-anniversary dinner complete with token jelly wobble. What did Jurassic Park mean to you?

SM: I was 12 when Jurassic Park came out. I went to see it with my first boyfriend. We held hands in the queue, it was a very special moment. I think for me, because I was a young teenager, it made liking dinosaurs and thinking dinosaurs were interesting and cool a little bit more socially acceptable, which as a girl in the early ’90s wasn’t always necessarily the case.

I think it made the discipline a bit more socially acceptable and I think also, it made dinosaurs really stars in peoples’ minds. It brought them to the forefront, and I think that did a lot for palaeontology as a whole because it increased funding to the discipline, and really shone a light on dinosaur research, which helps all of us in the end.

Absolutely. So, as far as the science goes it seems like cloning dinosaurs is probably not that likely but then, what is it they say?

This interview was part of IFLScience, The Big Questions. Subscribe to our newsletter so you don’t miss out on the biggest stories each week.

Source Link: Can We Bring Back Dinosaurs, And Is Anyone Trying To?