Stunning works of art on cave walls at places like Lascaux and Chauvet are among humanity’s treasures, offering insight both into the ecology of a lost world and the talents and psychology of our ancestors. Although most famous for realistic depictions of animals, European Upper Paleolithic art also includes abstract symbols, of which at least 32 have been identified.

In a new study, independent researcher Bacon Bennett and co-authors focus on the three most common of these non-figurative symbols. They claim these vertical lines, dots, and

“We demonstrate that when found in close association with images of animals the line <|> and dot <•> constitute numbers denoting months,” the authors write.

More ambitiously, the paper claims; “We also demonstrate that the

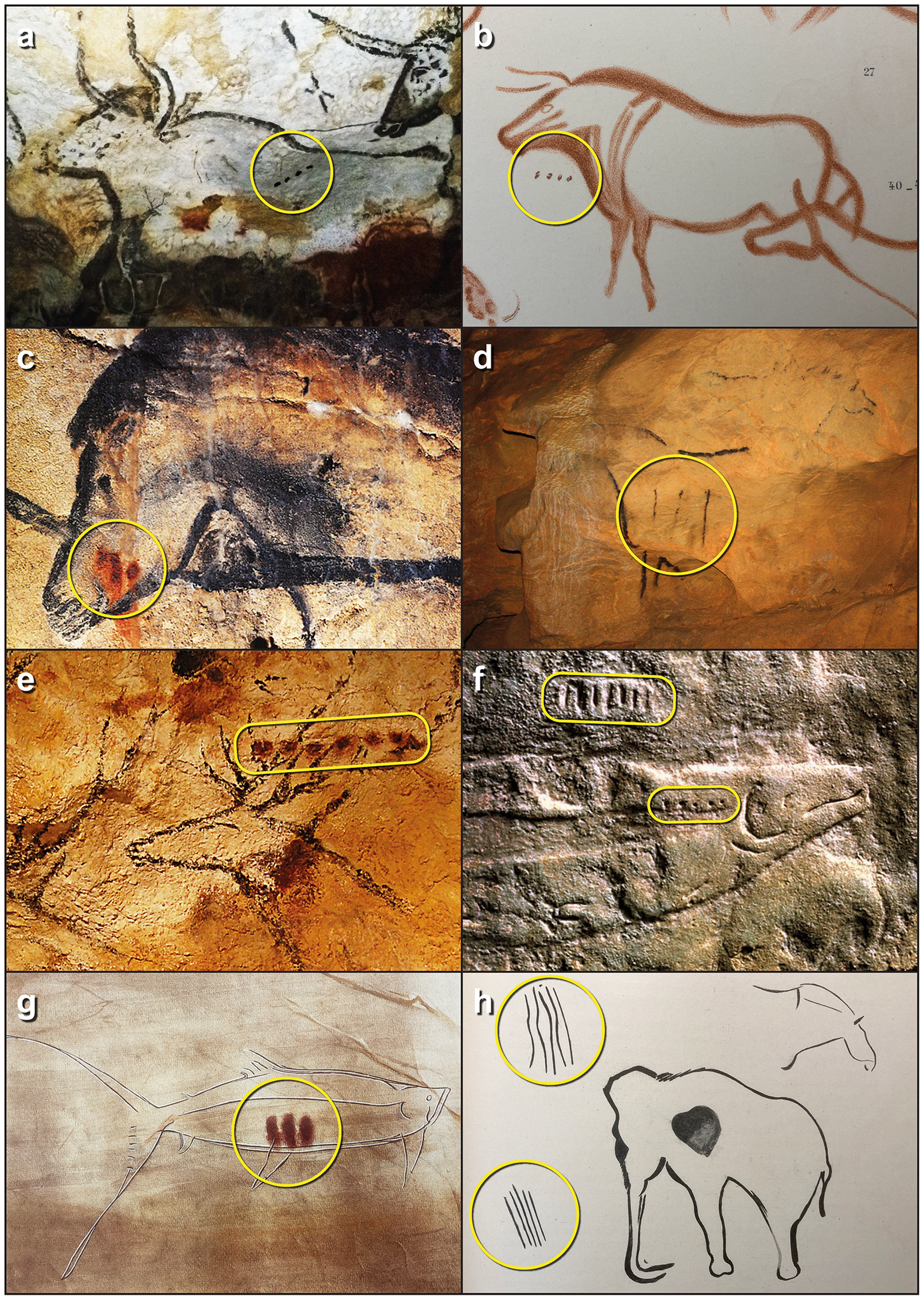

Dots and dashes accompanying animals from Western and Central European cave art with dots and lines circled (a-b) Aurochs(c-d) Horse (e) Red Deer (f) Salmon (g) Salmon (h) Mammoth. Image Credit: Bacon et al./Cambridge Archaeological Journal

The markings could provide an indication of the optimum timing for hunting specific species.

If true, the claims would represent the biggest advance in understanding cave art since its modern rediscovery, as well as transforming our understanding of the origins of writing. Such extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof, which it’s far from clear the authors have.

The paper notes the three symbols discussed became more common towards the end of the Palaeolithic, 20-12,000 years ago, over a wide geographic area, which might indicate they were conveying increasingly useful information.

The paper proposes the symbols’ original use may have been in indicating numbers for animals portrayed next to them on the wall. However, they could have subsequently evolved to convey more complex messages, such as timing.

There are too few marks in any single painting for them to say anything useful if they represent days. On the other hand, if a sequence represents the number of months, they could indicate the time required between some initiating event and optimum hunting times.

The animals portrayed are almost always prey species, which would have been most vulnerable around the time their young were born. Knowing when to anticipate this would have been vital information for hunting people, particularly in the depths of the Ice Age when other foods were scarce.

As the authors note, the counting of months would need to be “anchored to a well-defined start date,” which they propose was the unfreezing of rivers in late spring. Although the timing of this event would have varied across Europe, for people largely restricted to a particular location, the important thing would have been how long after the local thaw individual species gave birth.

The authors test their hypothesis by constructing a database of 256 sequences of dots, lines, and

Some of the species depicted, such as mammoths and woolly rhinos, are extinct, and their birth cycles unknown. However, the authors claim that for survivors, the sequences without

However, Dr Melanie Chang of Portland State University told Live Science; the authors; “Hypotheses are not well-supported by their results, and they also do not address alternative interpretations of the marks they analyzed.” Chang proposed two alternative explanations for the

The first three authors of the paper are not associated with scientific institutions. This may increase the difficulties they face in convincing their professional counterparts they have cracked a 20,000-year-old code, whether or not they can provide plausible explanations for less common symbols in the future. On the other hand, co-author Professor Paul Pettitt of Durham University told The Guardian he was; “Glad he took it seriously,” when Bacon contacted him.

The paper is open access at the Cambridge Archaeological Journal

Source Link: Cave Art Symbols May Be Earliest Written Proto-Language, But Claim Faces Skepticism