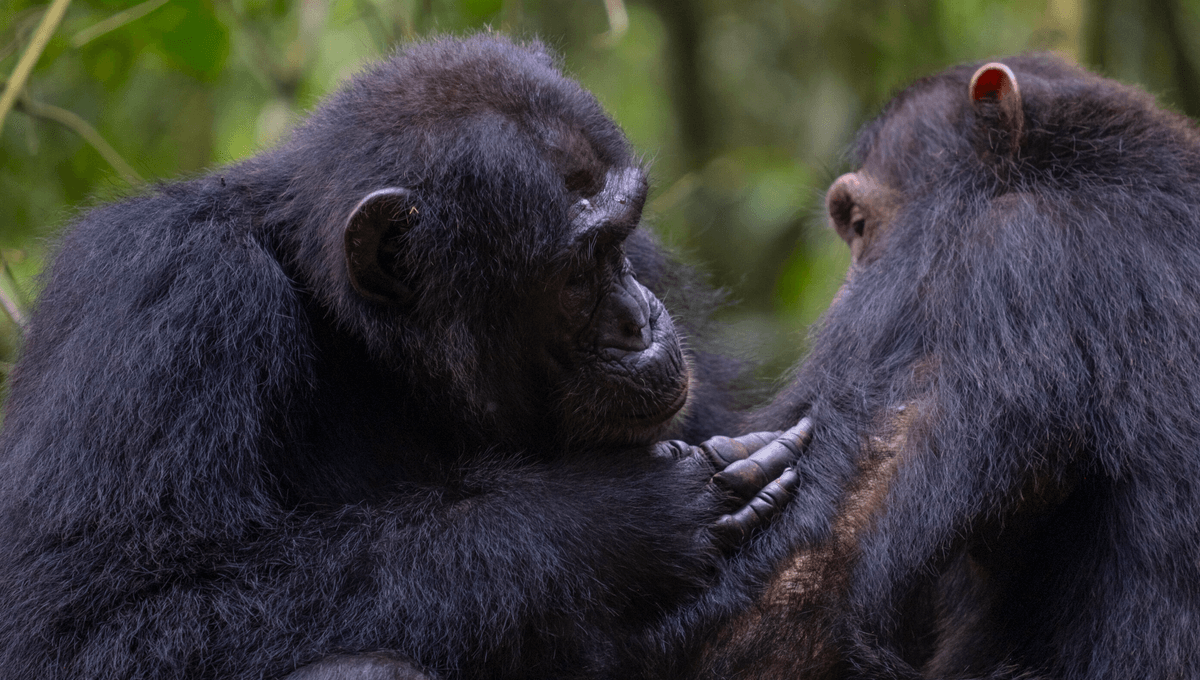

A troop of chimpanzees have been observed treating each other’s wounds and injuries, demonstrating both an understanding of the healing power of certain plants and care for others, irrespective of genetic relationship.

Chimpanzees heal a lot faster than humans, but they still sometimes need help. Last year, it was observed that our closest living relatives are aware of the medicinal properties of some antibacterial and anti-inflammatory plants and will seek them out when suffering from appropriate illnesses. Great apes are also known to self-medicate, from gorillas to orangutans. This is known as zoopharmacognosy (you can read more about animals’ use of medicine in Issue 24 of our e-magazine, CURIOUS).

However, new evidence shows that finding a cure is not always left to the sick animal. At least among the chimps living in the Budongo Forest, Uganda, a form of universal healthcare applies where one chimpanzee will treat another when the need arises. The study also reports chimpanzees sometimes use leaves to clean themselves after sex.

Around 40 percent of members of the Sonso community of chimpanzees have been observed suffering injuries from hunters’ snares. That’s in addition to the harm that can come from fights, accidents or transmissible disease.

Scientists studying the Sonso community, and their neighbors the Waibira chimpanzees, made detailed observations of any plants seen being applied externally, and then investigated them for medicinal properties.

Over the space of four months, 12 injuries were observed in Sonso, all from fights. Life was better for the Walbira, where only five injuries were observed, four from fights and one from a snare.

The team report 41 cases of medical application, some from the four-month observation period, but others from 30 years of archival records of the two populations. Of these, 34 were by the sick chimp themselves. Some of the behaviors observed are common among other animals, such as licking the wound. The chimpanzees also made use of the antimicrobial molecules in saliva by licking a finger and pressing it to the wound.

However, there were also cases of harnessing the rainforest pharmacopeia, pressing leaves with antibiotic or antifungal properties to wounds and chewing plants before applying them. There were also nine cases of chimpanzees wiping their genitals with leaves, almost always after sex. One chimpanzee also apparently invented toilet paper, using leaves for the purpose.

“All chimpanzees mentioned in our tables showed recovery from wounds, though, of course, we don’t know what the outcome would have been had they not done anything about their injuries,” said Dr Elodie Freymann of the University of Oxford in a statement. “We also documented hygiene behaviors, including the cleaning of genitals with leaves after mating and wiping the anus with leaves after defecation—practices that may help prevent infections.”

The seven cases of care for others involved two where chimpanzees attempted to assist in removing a snare, four treatments of wounds and one where a female cleaned a male’s penis with leaves after they’d had sex. Notably, no pattern in age, sex, or genetic relationship could be seen for either carer or recipient.

“These behaviors add to the evidence from other sites that chimpanzees appear to recognize need or suffering in others and take deliberate action to alleviate it, even when there’s no direct genetic advantage,” Freymann said. You could even call it empathy, which is clearly not a chimpanzee weakness.

Pro-social care has been reported often among chimpanzees in captivity, including teeth cleaning and help in removing an infected tooth.

Cases like this have been reported in the wild beyond Budongo, including the remarkable case of flying insects being applied to wounds, but not often.

That rarity may reflect observing failures, but Freymann and co-authors also speculate that the pressure Budongo chimpanzees face from snares could be driving greater mutual support than in most wild populations. The fact that care was seen more often among the Sonso, who experience more hunting pressure than the Waibira, could be evidence for this. However, Freymann is cautious, noting the Sonso are easier to observe because they are more habituated to human presence, so we may just be spotting a larger proportion of cases.

Freymann and co-authors note there are reports of other mammals, and even carpenter ants, caring for the wounds of other members of their species, but these are usually between close kin. Many more observations will be needed to detect patterns. Nevertheless, “Our research helps illuminate the evolutionary roots of human medicine and health care systems,” Freymann said.

The study is open access in Frontiers in Ecology of Social Behavior.

Source Link: Chimps Use Healing Plants To Treat Each Other’s Wounds And Clean Up After Sex