For the first time, scientists have been able to detect chronic pain as it happens, using electrodes implanted in the brains of four human volunteers. The detected brain signals could accurately predict an individual patient’s pain levels, and could one day lead to a solution to chronic pain where other treatments have been unsuccessful.

Chronic pain is a major public health concern. It affects around one in five people in the United States, making it more common than diabetes; but still, clinicians have no way of objectively measuring or quantifying it, making treatment even more of a challenge.

In a new study, four patients with refractory chronic pain – those whose pain could not be relieved using other medications or therapies – underwent surgery to implant electrodes into their brains. The patients all had nerve pain limited to one side of their bodies. One had phantom limb pain, and the other three all had pain brought on by a stroke.

The electrodes were similar to those used for deep brain stimulation (DBS), a treatment that’s already approved for use in some cases of Parkinson’s disease and other disorders. They were rigged up to record brain activity in two key regions associated with chronic pain: the anterior cingulate cortex and the orbitofrontal cortex.

The orbitofrontal cortex is of particular interest to researchers because it is a less well-studied area of the brain. Studies using brain stimulation to combat chronic pain go back decades, but limited progress has been made, prompting the study authors to look for a new approach this time.

Once the electrodes were implanted, the patients were able to go about their daily lives as normal. This is a big advantage compared to previous pain studies that have had to be done in a lab environment, as it allows the authors to build up a truer picture of the unique individual patterns of pain these patients experience.

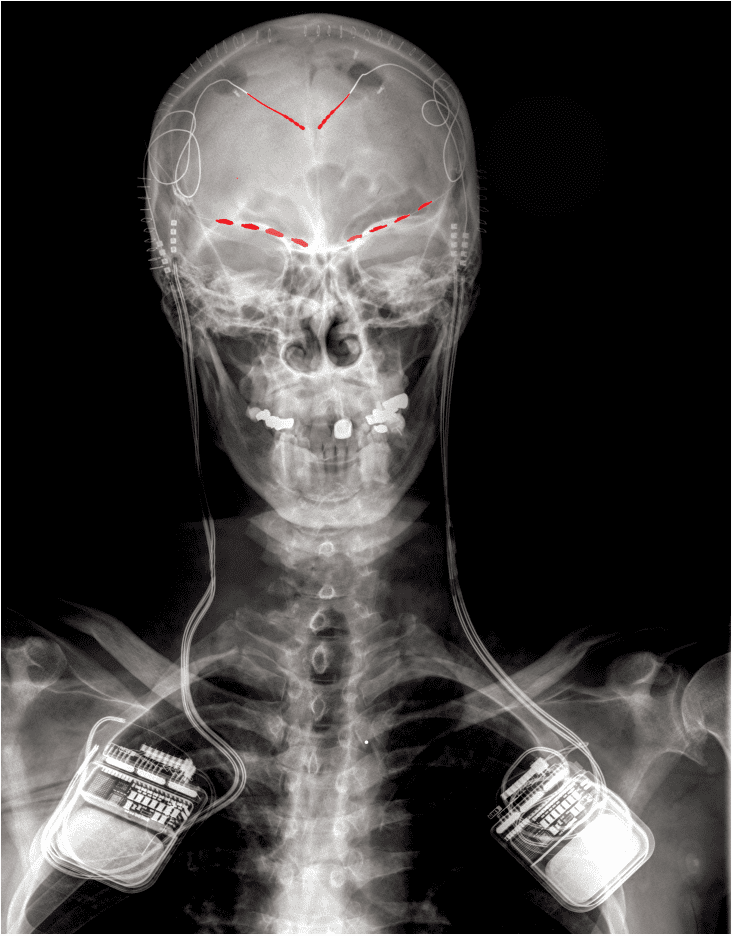

This X-ray, taken of one of the study participants, shows where the electrodes (in red) were implanted in the brain, as well as a recording/stimulating implant on each side.

Image credit: Prasad Shirvalkar

For three to six months, the patients were asked to complete regular questionnaires rating their pain, and at the same time to use a remote to instruct their electrode to take a snapshot of brainwave data. Using machine learning models trained on each person’s data, the authors were able to start accurately predicting the patient’s pain severity scores by looking at their brain activity.

They found that each patient almost had their own pain “fingerprint”, observable patterns and fluctuations in the data. However, despite the uniqueness of their experiences, the patients did also have some features in common: all of them showed activity patterns in the orbitofrontal cortex associated with their pain.

Additionally, the team observed that chronic pain differed from acute pain, which was linked more closely to the anterior cingulate cortex.

The study represents a landmark in that it is the first time that direct, in-human detection of brain activity associated with chronic pain has been achieved. While this work begins with only a small number of patients, these are patients whose pain has been particularly difficult to treat.

The electrodes aren’t only able to record data. In DBS, similar electrodes are used to deliver electrical stimulation to target brain regions to treat specific symptoms. The eventual aim of this study was not only to detect pain, but also to hopefully find a way to use the electrodes to provide some relief for these patients.

A clinical trial to investigate this has begun but is still in its very early stages. Speaking at a recent press briefing, first author Prasad Shirvalkar of the University of California San Francisco explained that, if everything works out, the team would like to explore more noninvasive methods – implanting electrodes into the brain is not without risk, and it’s important to remember that this is very much considered a last resort for these patients.

Ideally, it will eventually be possible to deliver personalized brain stimulation only when it is needed, to minimize potential side effects. The only way to do that is to gain a better understanding of the brain activity patterns that herald the onset of pain in a particular patient, and how these relate to the patient’s experience – and that is precisely what this study has started to do.

The study is published in Nature Neuroscience.

Source Link: Chronic Pain Detected Directly From The Human Brain For The First Time