Citizen scientists have detected “comet-like activity” around 2009 DQ118, an object supposed to be an asteroid. It’s a further example that classifications of objects in our Solar System are more about our convenience than eternal truths about being either one thing or another.

The Active Asteroids project had volunteers search through archival data of 2009 DQ118 to see if it had displayed any “comet-like activity”. They found more than 20 images from March 2016 where a team from the project write that it showed “clear signs of a comet-like tail”. Follow-up observations with the Magellan Baade Telescope (at 6.5 meters (21.3 feet) wide the same size as JWST’s main mirror) revealed the activity re-occurring during a close approach to the Sun this year.

True cometary behavior is caused by ices turning directly to gas (subliming) as their temperatures rise past melting point. There are a variety of explanations for active asteroids that can appear comet-like. A collision between two asteroids can throw off dust that forms a comet-like cloud. Other asteroids spin so fast they overcome their own gravity, throwing material off their surface. Phaethon is thought to get hot enough it fractures on approaching the Sun, releasing material.

Yet none of these explanations appears consistent with the observations of 2009 DQ118. The first two should not peak only when an object is closest to the Sun, while the other requires an approach much closer than 2009 DQ118’s. Might this actually be a comet disguised as an asteroid? Or could there be some unknown process that turns asteroids active? The Active Asteroids team recommend further investigation.

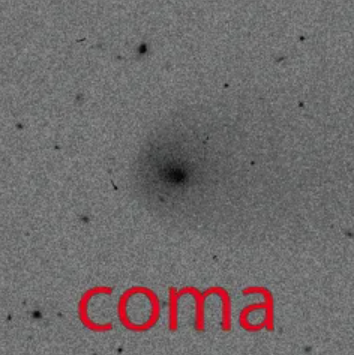

We think of a coma like this as a feature of a comet, but active asteroids can look just the same.

The Hildas are a group of asteroids and comets that exist between the main asteroid belt and the Trojans that share an orbit with Jupiter. They have a 3:2 orbital resonance with Jupiter – that is they complete three orbits in the time Jupiter makes two. Jupiter’s mighty gravity locks in place an asteroid that enters such an orbit, so we know of 5,000 and there are no doubt many more.

2009 DQ118, however, is not a Hilda, but a quasi-Hilda. Not pirated copies of the popular TV series, these are objects temporarily influenced into a Hilda-type orbit, but can also be shaken loose, similar to Earth’s quasi-moons. Ancient Greek tales of Jupiter’s behavior had a certain truth to them – it was unwise to cross the king of the Gods. Many quasi-Hilda comets that briefly break free of their resonance end up splattering into Jupiter, probably including the most famous comet to die by Jupiter impact, Shoemaker-Levy 9.

Telling a comet from an asteroid at this distance can be tricky, however, and the status of many quasi-Hildas is uncertain. A generalization close enough even NASA uses it in outreach is that asteroids are rock and comets are mostly ice. However, it’s possible to be a mix of both, and we often categorize objects before we know their composition, using their orbits. On approaching the Sun, ices turn to gas, producing “cometary activity”, including the familiar tail opposite the Sun, but out near Jupiter, most ices stay frozen.

Even tails, the feature considered most distinctive of comets can sometimes be seen trailing asteroids.

This is another example of the increasingly common phenomenon of non-professional scientists helping find something computers still can’t, and paid scientists lack the time to detect.

If it looks like a comet (at least on approaching the Sun), does that make 2009 DQ118 a comet? Well no, not according to astronomers’ definitions. Less than 50 active asteroids are known, making each one valuable in helping understand why the boundary between asteroid and comet can be as fuzzy as comets appear.

Why active asteroids exist, but represent such a tiny portion of Hildas, is also an unexplained problem, and the quasi-Hildas may hold the key. Quasi-Hildas have orbits that are just outside the 3:2 ratio with Jupiter. Their orbits can be Hilda-like for thousands of years, before escaping the resonance. Only about 5 percent of quasi-Hildas have so far been found to display comet-like activity, but that’s still much higher than among the true Hildas or other asteroids. Moreover, many of these discoveries are recent, suggesting there could be a lot more active asteroids lurking among the quasi-Hildas, still to be found.

Some asteroids are mostly iron, so it makes sense active asteroids would pump it.

The existence of these active asteroids from whatever class indicates the Solar System has reserves of volatile ices whose distribution and origins are not well known. One day, they could even be a valuable resource for space exploration missions.

Active Asteroids is designed to help uncover more of these objects. It is hoped that patterns in what is found could explain where such objects come from.

The study is published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Source Link: Citizen Scientists Find An Object Blurring The Line Between Comet And Asteroid