A cache of 57 coded letters, sent over four centuries ago by none other than Mary, Queen of Scots while she was imprisoned in England by Elizabeth I, has been discovered and decrypted by a team of international scholars.

Thought until now to be lost or destroyed, the letters turned up in precisely the kind of place you might expect: the online archives for enciphered documents at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BnF).

As part of the multidisciplinary DECRYPT Project – which aims to map, digitize, transcribe, and decipher historical ciphers – it was a natural place for the team behind the find to start their search.

What was less convenient, however, was the fact that they had been crucially mislabeled: the BnF catalog had listed the letters as dating from the first half of the 16th century, and being related to Italian matters.

In fact, the letters were written between 1578 and 1584 in French, and are unrelated to Italy. The team’s analysis of the letters quickly revealed mentions of the writer being in captivity, as well as the name “Walsingham” – Queen Elizabeth’s chief spymaster, whose investigations would eventually lead to Mary’s execution on February 8, 1587.

“Upon deciphering the letters, I was very, very puzzled and it kind of felt surreal,” said computer scientist and cryptographer George Lasry in a statement on the discovery. “We have broken secret codes from kings and queens previously, and they’re very interesting but with Mary Queen of Scots it was remarkable as we had so many unpublished letters deciphered and because she is so famous.”

That fame – or perhaps infamy – came thanks to the religiously-charged time in which Mary lived. England was only ten years into embracing Protestantism when she was born in 1542. By 1558, when Elizabeth I ascended the throne, the country had already ping-ponged between Anglicanism and Catholicism no fewer than three times as various monarchs took the rein. Each had been vicious in their proselytizing: the Catholic Queen “Bloody” Mary, for example, the eldest child of Henry VIII, and Queen Elizabeth’s half-sister, had been responsible for the burning alive of nearly 300 Protestants – including pregnant women – in the five years of her rule.

Queen Elizabeth I was less aggressive in this respect than her predecessors – she famously declared that she “[had] no desire to make windows into men’s souls,” repealing the heresy laws and lessening the punishments for those who refused to conform to the Church of England. However, many Catholics in the country still believed that a Protestant monarch could not be legitimate, and they were willing to fight for a Catholic to replace her – and, in 1569, that’s exactly what they did.

The Rising of the North was an unsuccessful rebellion, but it was enough to shake Elizabeth and her advisors. It had been an attempt by Northern Catholics to depose the English Queen and replace her with the person they saw as the legitimate Catholic ruler: Henry VII’s granddaughter, and Elizabeth’s cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots.

By this point, Mary had already spent two years in captivity: she had been imprisoned by rebelling Scottish nobles after a scandal surrounding her marriage to the man thought to have murdered her first husband. She had managed to escape to England, hoping that Elizabeth would help her reclaim her throne, but the English queen was hesitant – she, too, imprisoned Mary (albeit in a huge castle with a full revenue of servants and finery) while she ordered a full inquiry into the murder and uprising that had led to Mary’s unseating.

But with the Rising of the North, Elizabeth realized that Mary was a real threat. Walsingham was assigned to watch her carefully, placing spies among her domestic staff and intercepting her many letters to the outside world, while she remained in captivity in England.

It’s those letters, written in code to avoid detection by Elizabeth and Walsingham’s spies, that the new discovery adds to. “Together, the letters constitute a voluminous body of new primary material on Mary Stuart – about 50,000 words in total, shedding new light on some of her years of captivity in England,” Lasry noted.

Those insights range from the mundane – like complaints about her poor health and captivity conditions – to the lofty, such as her opinions on international relationships and musings on her negotiations for her release. Most of the letters are addressed to Michel de Castelnau de Mauvissière, the French ambassador to England at the time, and a supporter of Mary.

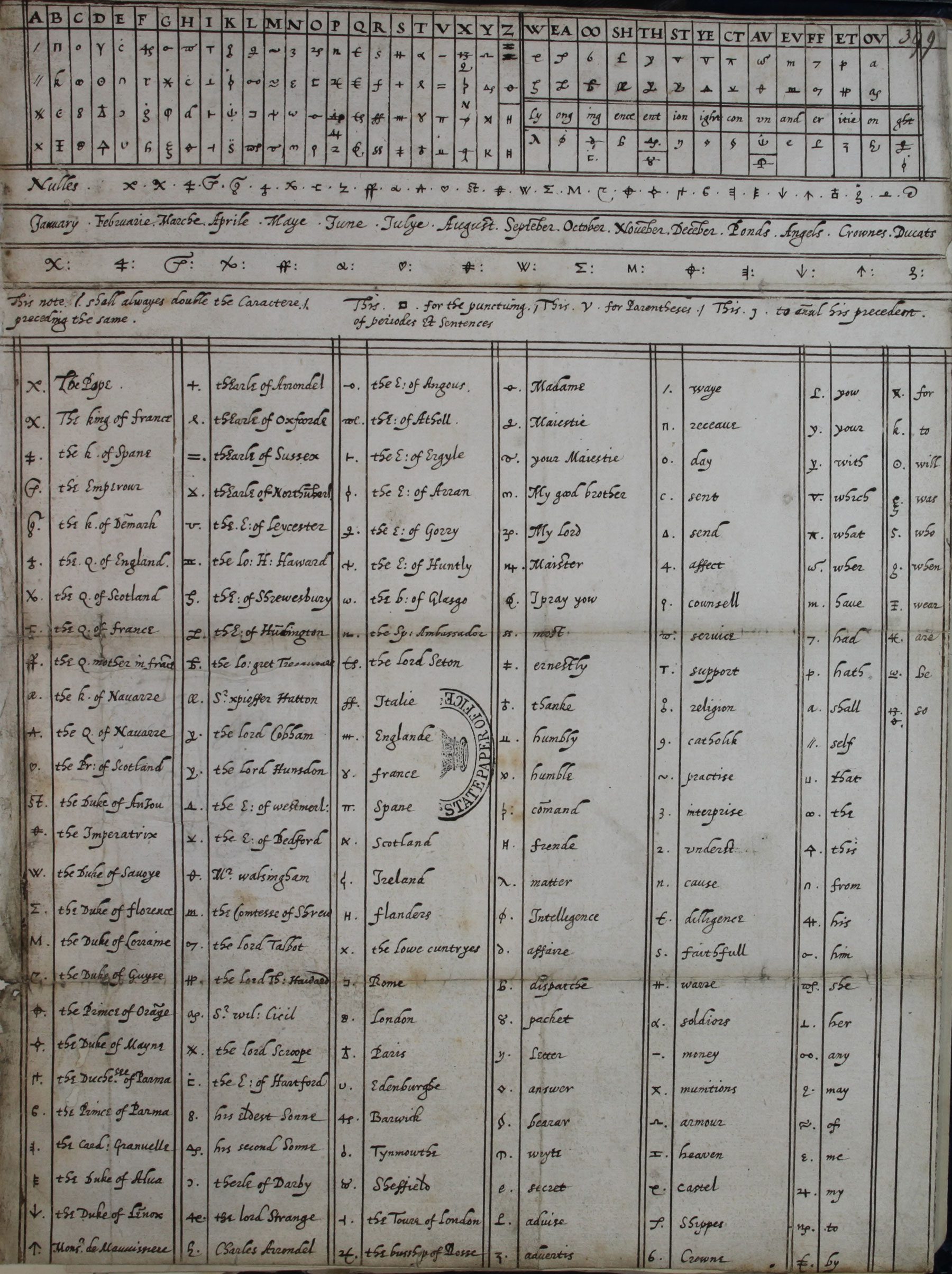

The cipher and code tables of Mary, Queen of Scots, from the collections of The National Archives (United Kingdom). Image credit: Public Domain, via The National Archives (United Kingdom)

“Mary… left an extensive corpus of letters held in various archives,” Lasry said. “There was prior evidence, however, that other letters from Mary Stuart were missing from those collections, such as those referenced in other sources but not found elsewhere.”

“The letters we have deciphered… are most likely part of this lost secret correspondence,” he added.

Eventually, though, Mary’s prodigious pen-palling would be what led to her downfall. Many unsuccessful plots to depose Elizabeth and replace her with Mary were uncovered during the 19 years that the Scottish queen was kept imprisoned, but one in particular – the Babington Plot – caught Mary red-handed, plotting to assassinate the Queen.

Despite writing her letters to her co-conspirators in code, Walsingham’s spies had by this point cracked her encryption system. Less than seven months after Mary wrote the letter signing off on the assassination of Elizabeth I, she was facing her execution for high treason at Fotheringhay Castle, in Northamptonshire.

Thanks to the controversy and drama surrounding her life, Mary has become something of a tragic romantic heroine in the eyes of many – and with the new trove of letters, the researchers hope to reveal more of Mary’s troubled, if gilded, life.

“In our paper, we only provide an initial interpretation and summaries of the letters. A deeper analysis by historians could result in a better understanding of Mary’s years in captivity,” Lasry suggested. “It would also be great, potentially, to work with historians to produce an edited book of her letters deciphered, annotated, and translated.”

“This is a truly exciting discovery,” he said.

The findings are presented in the journal Cryptologia.

Source Link: Codebreakers Crack Secrets Of Mary Queen Of Scots' Lost Letters