In basic terms, the Sun doesn’t make sense. Its photosphere, the outer shell from where light is radiated, has a temperature of about 5,600 °C (10,000 °F). Above it, there is the solar corona, which is in the millions of degrees. How the solar corona is heated to such incredible temperatures remains a mystery. A new paper has found a possible source – and it’s from the coldest parts of the photosphere: the sunspots.

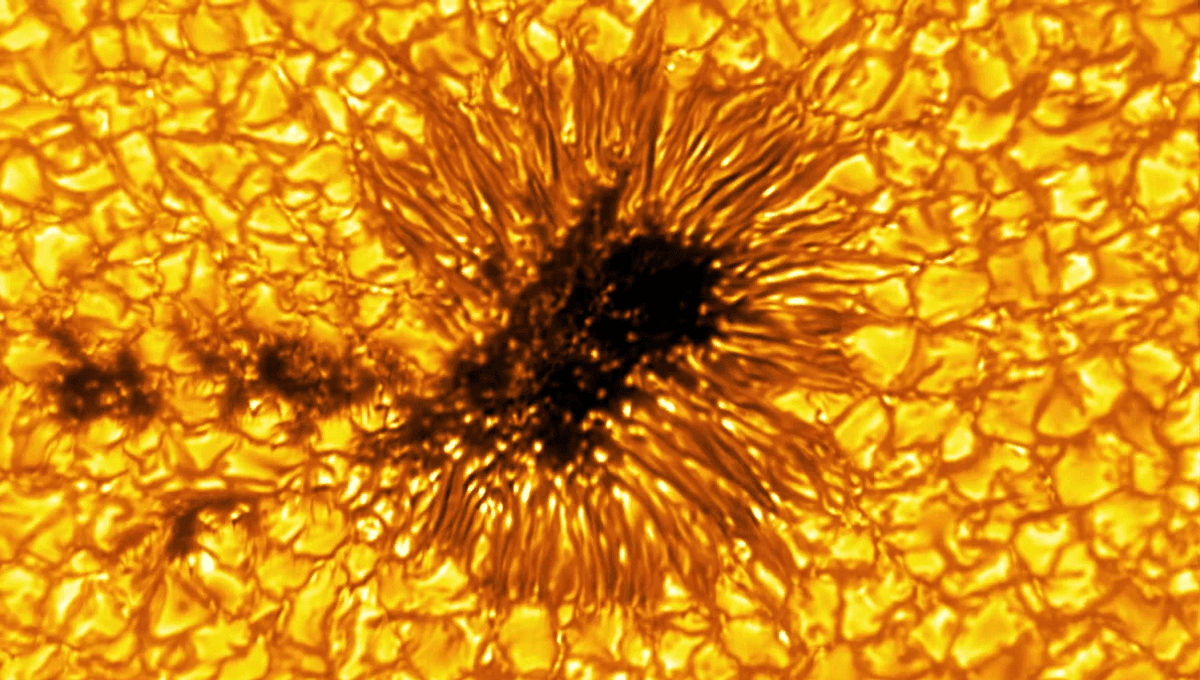

These regions are cooler than the average photosphere and are caused by the magnetic field of the Sun protruding from the interior. They are dark because they are cooler than their surroundings. They are also the site of major magnetic events such as solar flares and coronal mass ejections.

The team used the 1.6-meter (5.2-foot) Goode Solar Telescope (GST) at Big Bear Solar Observatory (BBSO) to study features called plasma fibrils. The fibrils are located in the darkest part of the sunspot, the umbra, and have magnetic fields more than 6,000 times stronger than Earth’s own. And they appear to deliver enough magnetic energy to explain the heating in the corona.

“Fibrils appear as cone-shaped structures with a typical height of 500-1,000 kilometers [310-620 miles] and a width of about 100 km [62 miles],” Vasyl Yurchyshyn, professor of heliophysics and BBSO senior scientist said in a statement. “Their lifetime ranges from two to three minutes and they tend to reappear at the same location within the darkest parts of the umbra, where magnetic fields are strongest.”

“These dark dynamic fibrils had been observed in the sunspot umbra for a long time, but for the first time, our team was able to detect their lateral oscillations that are manifestations of fast waves,” Wenda Cao, BBSO director and physics professor who is co-author of the study, added. “These persistent and ubiquitous transverse waves in strongly magnetized fibrils bring energy upwards through vertically elongated magnetic conduits and contribute to the heating of the upper atmosphere of the Sun.”

The fibrils’ role is intriguing but the team admits that even if this process can explain the heating over sunspots, it is not an all-encompassing process to explain the heating of the whole corona. The puzzle continues.

“The coronal heating problem is one of the biggest mysteries in solar physics research. It has existed for nearly a century,” Cao continued. “With this study we have fresh answers to this problem, which may be key to untangling many confusing questions in energy transportation and dissipation in the solar atmosphere, as well as the nature of space weather.”

The study is published in Nature Astronomy.

Source Link: Coldest Spots On The Sun Might Be Heating The Million-Degree Corona