Finance can be a tool in the climate crisis, but how and where we spend the money will decide how powerful it is. Carbon credits and earth technologies that have existed for billions of years could see historically undervalued parts of the planet make well-deserved money while simultaneously securing a future for humans across the globe, if only we would let them.

It all sounds a bit too good to be true, doesn’t it? The truth is that not all carbon credits are made equal, but establishing a prosperous and equitable alternative market could turn preventing our own extinction into an opportunity to sponsor the people across the globe who are working for the planet, not against it.

But first of all, a recap.

What are carbon credits?

In 1997 most countries in the world signed up to the Kyoto Protocol, part of which involved what’s called the emission trading scheme. This meant that countries with high emissions could offset their footprint by giving money to countries with lower emissions, in the form of buying units of carbon.

Carbon credits, as those units are known, mean that big corporations can improve their environmental image by giving money to the countries that are keeping their emissions low, even if those same companies are continuing to carry out Earth-warming practices. This is how flight companies are able to make promises of carbon-neutral journeys: not because they’ve invented an emissions-free version of flying, but because they’ve bought back enough credits to balance out the harm, so to speak.

It was a fine idea in theory, but in practice the carbon credits scheme has been abused.

What are phantom credits?

Phantom credits have snuck into the trade to catastrophic effect, with the potential to actually worsen global heating rather than offsetting it, as carbon credits have been made out to do. They’re essentially poor-quality carbon credits that don’t fulfil promises made to emissions and the environment, and they can come about in many ways. Largely, it boils down to lack of quality control among carbon credits, and a lack of transparency as to where the money goes.

The threat phantom credits pose to the market was demonstrated in recent research into Verra Carbon Standard that found most of the “carbon credits” traded were in fact these phantom credits that do nothing for the planet. The results followed a nine-month investigation from UK newspaper The Guardian, in alliance with German weekly Die Zeit and SourceMaterial, a non-profit journalistic organization.

It concluded that 90 percent of the carbon credits claimed by Verra are phantom credits, and that the 94.9 million metric tonnes of CO2 equivalent claimed actually only represents 5.5 million. Verra have disputed the findings, but investigations by The Guardian indicated they were overstating the threat to forest projects by 400 percent, and that human rights issues were a serious concern in at least one of the offsetting projects.

Not all carbon credits are created equal

These concerns were raised by Timothy Kamuzu Phiri, Executive Director of Mizu Eco-Care in Zambia, at the Born Free Foundation’s Beyond Trophy Hunting talk in December 2022. During the talk, he explained why the quality of carbon credits is instrumental not only to the systems’ success in achieving climate goals, but also in achieving transparency about who benefits from carbon credits and whether that financial reward is relative to their contribution.

“Are all carbon credits equal? The answer is no, and I’ll give an example of that,” he said. “If you look at carbon credit mechanisms like the [Northern Rangelands Trust] that’s taking place in Kenya, you will notice that the land on which this project is taking place is actually owned by local communities. That’s a good carbon credit mechanism.”

“Then you have carbon credit mechanisms that take place on private land, that means you have to drive out communities from that land. […] That’s not a good mechanism. Then you have management teams that run that particular project not being transparent with the funds being raised, they’ll tell you $5 million was given to the community from this mechanism, but you do not have any idea what the total amount generated was.”

“If the total amount generated was $50 million then $5 million doesn’t look like a lot of money. The local communities will be poor so when they see the 5 million, they will be celebrating, but the mechanism is unjust.”

Are carbon credits our only option?

No, quite simply, and neither is trading with private landowners. “Indigenous communities have coexisted with wildlife for time immemorial,” Grassroots conservationist and programme coordinator for the Ujamaa Community Resource Team (UCRT), Dismas Partalala Ole Meitaya, told IFLScience. “Since their livelihoods depend on healthy environments, protecting their land and natural resources is in their best interest.”

Community owned, run and led carbon credit and Earth tech options (more on these later) can not only bring revenue into historically impoverished areas, but also put that investment into the hands of the people who know best how to preserve the native wildlife and maintain their environment.

Some carbon credits are built on human suffering, as privately owned land forces out Indigenous communities. After displacing these people, the money given to these sites by corporations can then be reinvested into the very companies that got us into this mess in the first place, creating a feedback loop of profits from “carbon offsets” rewarding the companies with the highest emissions. Here, carbon credits can become a force for ill.

“Carbon credits offer the opportunity for trade-offs,” continued Phiri. “So, the organizations that provide the financing for the carbon credits get an opportunity to pay this money but keep on polluting. When they keep on polluting, they are continuing to do what brought us into this crisis anyway.”

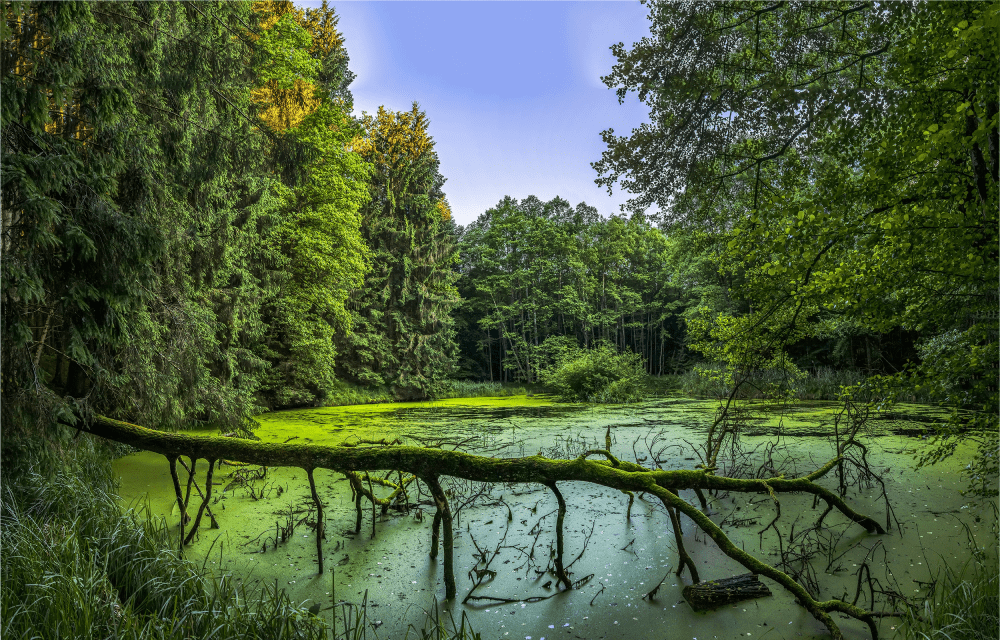

Draining swamps and peatlands for development could actually be reducing their value if Earth tech was valued in the same way as carbon credits. Image credit: apolinariy / Shutterstock.com

Can “Earth tech” see us finance our way out of the climate crisis?

Giving finance a seat at the table might leave a bad taste in the mouth of some conservationists who believe that simply wanting to do good should be enough to motivate our species not to set the world on fire. They’re right, but the reality is that money talks, and by introducing a diversified set of assets and quantifying their value both as environmental stabilizers and a way of offsetting brand emissions, we can create natural capital that will bring money to the people doing the necessary work to save our planet.

At Beyond Trophy Hunting, economist Dr Ralph Chami explained exactly how this could work with Nature Resilience Certificates, which would see buyers purchase “ecosystem services credits” using blockchain for transparency and traceability to see that all money goes to the right recipients: the Indigenous caretakers of natural capital, be that wildlife, biodiversity or ecosystems. The best thing about Earth tech is that it’s already here, and has been tried and tested for billions of years, we just need to work out how to value and trade it like any other commodity.

Imagine you’re a landowner in possession of a swamp, and you’re faced with two choices; one, you could dredge the swamp and clear the land to build a luxury hotel; two, you keep the swamp and make money off the natural capital by allowing polluters to offset their emissions by investing in your carbon sink.

A luxury hotel might on the surface seem more appealing, but in a world where climate stabilizing technologies are becoming increasingly valuable, landowners may face better prospects by preserving wild spaces rather than bulldozing them.

An elephant should be on $70,000 a year

The same applies to wild animals. One of the most popular reasons given for the preservation of trophy hunting is that it brings money to Indigenous communities. This argument has been contested, but say we assume it’s true: is the value of an elephant being shot once greater than the carbon sequestration it achieves across its lifetime? Conveniently enough, new research has just investigated the latter.

It observed that elephants are choosy when it comes to foraging, selecting the smaller plants and trees to rip to shreds for food. Curiously, these modestly-sized species are also the low carbon density trees, meaning they grow quickly and compete for resources, but actually do little in the way of storing carbon. High carbon density trees are bigger, grow slower, and sequester more carbon from the environment by taking CO2 and transforming it into biomass through photosynthesis.

By selectively munching on the smaller plants and trees that do little for the planet while competing with more environmentally beneficial species, elephants effectively thin the forest, promoting the species that are good for the climate while eating the ones that aren’t.

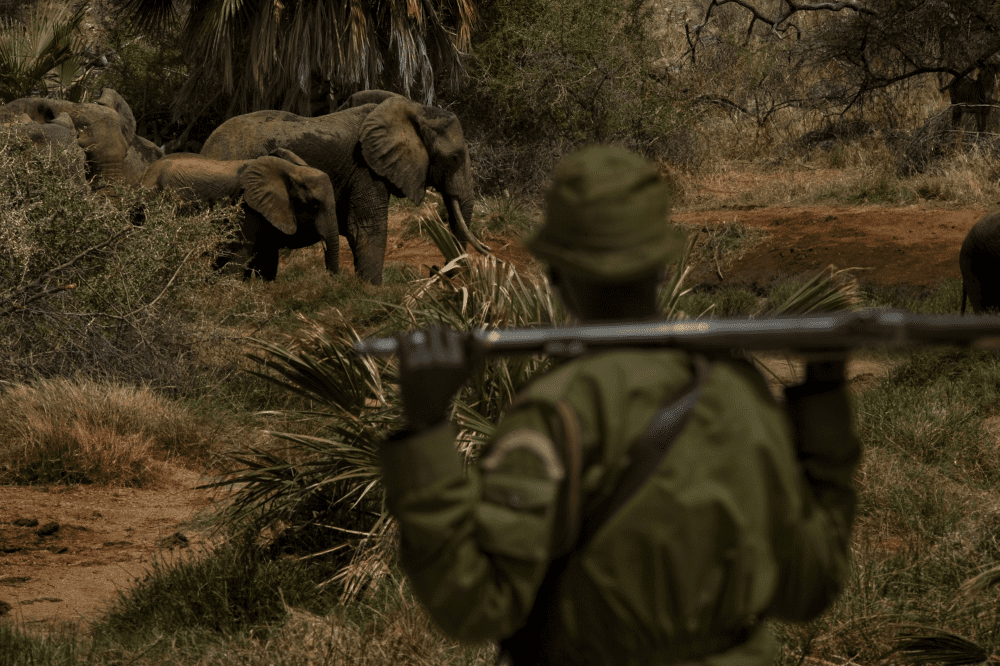

Nature has given us some amazing climate stabilizing technologies, but they need protection. Image credit: Ondrej Prosicky / Shutterstock.com

Elephants are also the gardeners of the forest, walking around eating fruits that turn into seeds and fertilizer in their digestive systems. This nutritious blend is carried around the forest in their stomachs so that it can later be dispersed as dung that’s travelled far from the parent trees. That dung then morphs into some of the biggest tree species in the forest, further contributing to the value of forest habitats as carbon stores.

Chami’s research into the environmental influence of elephants revealed that were a female elephant to ask for a salary, she could reasonably expect to be valued at around $70,000 a year. This is because a single forest elephant is worth around $1.75 million across its lifetime when it comes to carbon offsets, capable of sequestering around 9,500 tonnes of CO2 per kilometer-squared annually, which is good news for everyone.

So what can we do about it?

Carbon credits are arguably the most talked-about offsetting trade, but there’s scope for a wider range of ecological services to be brought to the table if we can find a way to work fairly and transparently with the countries and communities that share the Earth with us. There can be a future for the carbon credit too, but perhaps with a view to focusing on quality over quantity.

“I know [carbon credits are] the most popular mechanism taking place right now, if you look all the agreements that were being made at COP27: the majority of the handshakes involved carbon credit financing,” concluded Phiri. “Why is there so much financing going towards carbon credits, and very little financing going towards loss and damage, adaptation, mitigation, and aren’t those important?”

“Should the emphasis be on “net zero carbon emission solutions”? Or should the emphasis be on zero carbon emission solutions? My proposal is, 60 percent of the funding should go to zero carbon emission solutions and 40 percent of the funding should go to net zero carbon solutions, because net zero means 100 tonnes of carbon into the atmosphere, a hundred tonnes out. Zero carbon emissions means you’re just taking 100 tonnes of carbon [out of the atmosphere], which is a huge plus for climate action.”

If the climate crisis is allowed to continue the world may well go on without us, but if we want to be a part of its future we have to take what we’re good at – turning things into business – and make it work for the many, not the few.

If we act now, and not at a glacial pace, we can bring conservation to the right tables to make this happen. In getting the money to the right people the right way, and considering flora, fauna, humanity and the planet as equal stakeholders, it’s possible to achieve a win-win-win-win situation.

Now that’s a lot of winning.

Source Link: Could Ecosystem Services Outperform Carbon Credits In The Climate Fight?