To many, the Voynich Manuscript represents a 600-year-old mystery. The medieval text is filled with bizarre illustrations and is written in a hitherto indecipherable language. But for all its enigmatic features, two scholars believe they have solved at least one: the manuscript, they argue, is at least partially about sex.

A weird manuscript

The manuscript was named after Wilfrid Voynich, an antique bookseller who bought the text in 1912. Ever since then, there have been various attempts to decipher its meaning, with some suggestions being more plausible than others. Some believe it is a hoax, some argue that it is an alchemical text, while others have argued that its seemingly unusual language was written by aliens (of course).

The parchment was subjected to radiocarbon dating in 2009, which dated it – with 95 percent probability – to the years between 1404 and 1438. This means that that animals whose skins were used to make the pages lived and died around this time.

However, who made the manuscript remains unknown, nor do we know how many hands it passed through before the first identifiable owner. This was Jakub Hořčický z Tepence, the personal physician to Rudolf II, the Holy Roman Emperor. We know this because his name appears on the manuscript but was only identified through ultraviolet light in recent years. This means the manuscript passed between unknown people for over a century.

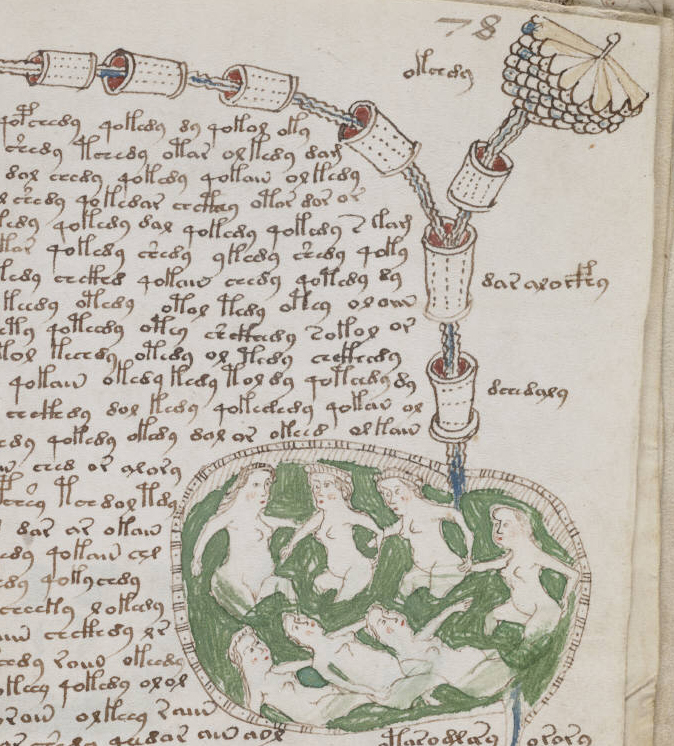

An example of the unusual imagery contained within the Voynich manuscript. This illustration is included in a balneological section of the text.

We do have a better idea of where it was created though. The details on certain illustrations, especially architectural features of castles, suggest it was made in southern Germany or in northern Italy.

It’s about women’s secrets

For some time, scholars have wondered whether the Voynich manuscript may have something to do with women and may have been written by women for women. However, new research by Keagan Brewer and Michelle L. Lewis suggests it does indeed relate to women, but actually contains enciphered information related to sexual matters.

They reached this conclusion by examining the work of the Bavarian physician Johann Hartlieb, who lived around the same time that the manuscript was created.

Hartlieb, they explain, wrote about plants, women, magic astronomy, and baths, but also recommended the use of cyphers to obscure “sensitive information”. In particular, he recommended their use when discussing medical recipes and procedures related to contraception, abortion, and sterility. The main concern for Hartlieb, the authors argue, was that the free circulation of this information would lead to extramarital sex, which would incur God’s wrath.

As such, we may not have Hartlieb’s original cypher, but an examination of his work and his unencrypted writing can yield a lot of information about contemporary attitudes and what may be concealed within the Voynich manuscript.

“While the motivations of the Voynich manuscript’s anonymous authors remain a matter for speculation and inference,” the authors write, “examination of the works of physicians from adjacent regions definitively reveals contemporary attitudes towards issues hinted at by the Voynich illustrations.”

From his work, we can see that Hartlieb resisted or was hesitant to write about topics related to female sexual matters. This included subjects like post-partum vaginal ointments, women’s sexual pleasure, speculation over unusual births (women giving birth to animals), dietary advice to alter the libido, and any information about dangerous compounds that may cause hallucinations and serve as a contraceptive or abortive.

Today, we may see this level of secrecy and esotericism as suspect, but it is perfectly in-keeping with the prevailing attitudes of his day. In fact, Hartlieb was not the only one to conceal such information behind cyphers, especially anything of a gynecological and sexological nature.

Knowledge was not for everyone and especially not for women, and yet women were becoming more literate during this period.

The Voynich manuscript’s secrets unveiled

Using this lens, Brewer and Lewis examined the Voynich manuscript’s largest illustrations – the Rosettes – and suggested they are a cryptic representation of the contemporary understanding of sex and conception.

“The Rosettes, the largest and most intricate illustration on the Voynich manuscript, has rightly received close attention,” they write, “but its layers of visual symbolism have caused it to be misunderstood until now.”

“The elaborate – and deliberate – symbolisms in the Rosettes constitute a form of visual encipherment that has excluded or confused the uninitiated for many centuries.”

During the late-medieval period, the uterus was thought to have seven chambers as well as two openings to the vagina. The authors contend that the nine circles of the Rosettes represent these chambers and entrances.

A castle that appears within the Rosette illustration may related to a German term that could also refer to female genitalia.

According to Abu Bakr Al-Rāzī, one of the most influential figures in the history of medieval medicine as well as Islamic tradition, virgins had five small veins in their vaginas. The authors believe these five veins are visible on the top left circle of the Rosettes and running towards the centre.

Another coded idea appears in the form of two horn-like protrusions on the top right and bottom right of the circles. These horns, they maintain, match contemporary beliefs that the uterus had two horns on its sides.

It is also possible that the castle that appears on the illustration may be a form of word play, where the German word schloss could refer to a “castle” or “lock”, but also female genitalia and “female pelvis”.

If they are right, then this adds a great deal to our understanding of this mysterious manuscript and shows that, in order to decipher it, we need to pay closer attention to the wider context of late medieval thinking.

As the writers conclude: “Overall, we infer that the creators of the manuscript, like Hartlieb, felt a mixture of passionate fascination and abject horror at the taboo subject matters collectively referred to as women’s secrets.”

“What we hope to have demonstrated in this paper is that amid the abundance of gynaecological and sexological writing drawn up in late-medieval Europe, there were large numbers of medical writers and readers who considered ‘women’s secrets’, or diverse aspects thereof, worthy of obscuration, sometimes in addition to other subjects such as alchemy, magic, and demons.”

The study is published in the journal Social History of Medicine.

Source Link: Could One Of The Mysteries Of The Voynich Manuscript Relate To Female Sex?