What’s 3 meters (10 feet) long, has huge teeth, big eyes, and hunted prey in ancient Scottish swaps over 300 million years ago? The answer: an extremely ferocious-looking crocodile-like carnivore called Crassigyrinus scoticus. Now, a team of scientists have managed to digitally reconstruct this beastie’s skull, which not only yields new insights into what it looked like but also how it may have lived.

Crassigyrinus, which means “thick tadpole”, is known as an early tetrapod (from the Greek Tetrapoda “four legs”) and was a large aquatic predator that lived in the coal swamps of Scotland and parts of North America during the lower- to mid-Carboniferous era. It is closely related to some of the first species to make the transition from water to land, although Crassigyrinus did not make it onto land itself.

Although scientists have been studying the remains of the aquatic animal for nearly a century, they have had difficulty understanding the 330-million-year-old species as all the known fossils have been severely crushed. This is because Crassigyrinus tended to be preserved in fine-grained rock which, as more layers of material piled up, subsequently squashed the remains.

So, what scientists have had to deal with, to date, is a lot of broken and misshapen bones and flattened fragments. Many of these pieces are also disordered and laid on top of one another other. This has made it extremely difficult for researchers to reconstruct what it may have actually looked like.

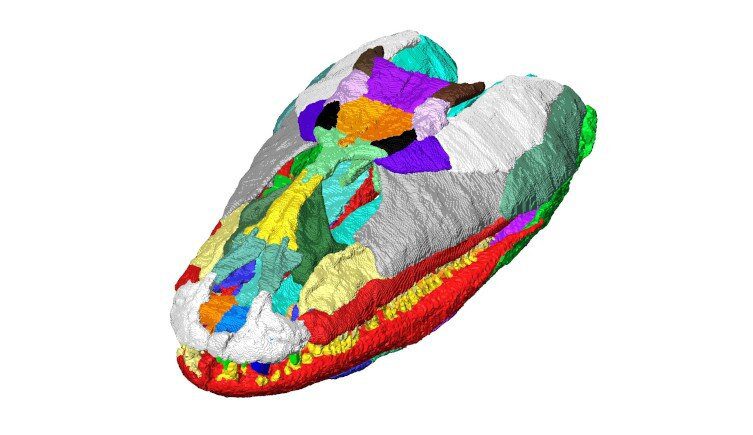

However, advances in computer tomography (CT) scanning and 3D visualization have allowed a team of researchers to put the fragments together again for the first time. They used pieces from four specimens where all of the bones from the skull were present.

“Once we had identified all of the bones, it was a bit like a 3D-jigsaw puzzle,” Dr Laura Porro of University College London, the lead author of the new study, said in a statement. “I normally start with the remains of the braincase, because that’s going to be the core of the skull, and then assemble the palate around it.”

“This animal”, Porro added “has previously been reconstructed with a very tall skull, similar to a Moray eel, based on the type specimen in Edinburgh which has been flattened from side-to-side.”

“However, when I tried to mimic that shape with the digital surface from CT scans, it just didn’t work. There was no chance that an animal with such wide a palate and such a narrow skull roof could have had a head like that.”

Instead, Porro found the animal had a skull similar to modern crocodiles, as well as large teeth and powerful jaws, all the better to eat anything that crossed its path. This information, paired with recent research into Crassigyrinus’ body, shows that the animal was quite flat-bodied with short limbs. This shines an important light on how the carnivore would have lived and helps explain how it would have been a fearsome predator.

“In life”, Porro explained, “Crassigyrinus would have been around 2 to 3 meters [6.5 to 10 feet] long, which was quite big for the time,” Laura says. “It would probably have behaved in a way similar to modern crocodiles, lurking below the surface of the water and using its powerful bite to grab prey.”

Interestingly, Crassigyrinus also had a range of specialized senses to help it track its prey. These included its large eyes that allowed it to see in the prevailing gloom of the coal swamps, but also lateral lines that detected vibrations in the water. There is also a strange gap at the front of its skull which may have given it other senses too.

“A lot of early tetrapods have midline gaps at the front of their snout, but the gap in Crassigyrinus is much larger and features smoothly sculpted edges,” Porro explained. “The nostrils were elsewhere, so there has been a lot of speculation what this opening might have been.”

One possibility is that Crassigyrinus, like some existing fish, may have had a rostral organ to detect electric fields. It could also be an early example of a Jacobson’s organ, which allows species like modern snakes and amphibians to detect different chemicals. Though this is all speculation, as whatever was in this gap has not been preserved.

With the new reconstructions, the researchers are experimenting with a series of biomechanical simulations to see what it was capable of doing.

The paper has been dedicated to co-author Professor Jenny Clack, a “pioneering paleontologist who revolutionized our understanding of early tetrapod evolution”, and who passed away in 2020.

The study is published in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Source Link: Crushed Fossil Pieces Used To Reconstruct Killer “Tadpole From Hell”