It’s been almost 40 years since the Chernobyl nuclear disaster saw the evacuation of around 120,000 people from their homes in northern Ukraine and Belarus. While the irradiated surrounding area is still home to very few people, some species of animal have beaten the odds to survive in this most unlikely of places.

Exposure to radiation can damage the DNA of living organisms and cause undesirable mutations. Barn swallows have previously been found to have two to 10-fold higher mutation rates in Chernobyl than in Italy or elsewhere in Ukraine. Meanwhile, voles living in the Exclusion Zone were found to be more likely to develop cataracts, a 2016 study concluded.

But it’s not all doom and gloom. Plenty of species are surviving, even thriving, in the shadow of the worst nuclear disaster in history.

Chernobyl dogs

Following the disaster, and subsequent evacuation, on April 26, 1986, many pet dogs were left to fend for themselves in the land surrounding the former power plant. Despite now being without owners and facing the threat of radiation, a sturdy population was established, which still exists today.

By the most recent estimates, as many as 800 semi-feral dogs are currently living around Chernobyl, including in some of the most contaminated areas. While the dogs largely fend for themselves, workers and researchers are known to feed the animals, and vets occasionally visit to provide vaccines and medical treatment.

The dogs have not been unaffected by the exposure to the radiation they’ve faced in their hostile home: a recent study found it may have made them genetically distinct from other dogs elsewhere in the world. So changed is their DNA profile that it is possible to tell who these dogs are just by looking at it, which the researchers believe is a reflection of the environmental contamination they’ve been exposed to for generations.

It is not yet known what impact this might have on the dogs’ health, appearance, and behavior, but their resilience in surviving almost four decades in such an unexpected place can’t be knocked.

Chernobyl frogs

Dogs aren’t the only species to have been changed by the harsh environment of Chernobyl. Some animals have developed adaptations to help them survive the radiation, including the Eastern tree frog.

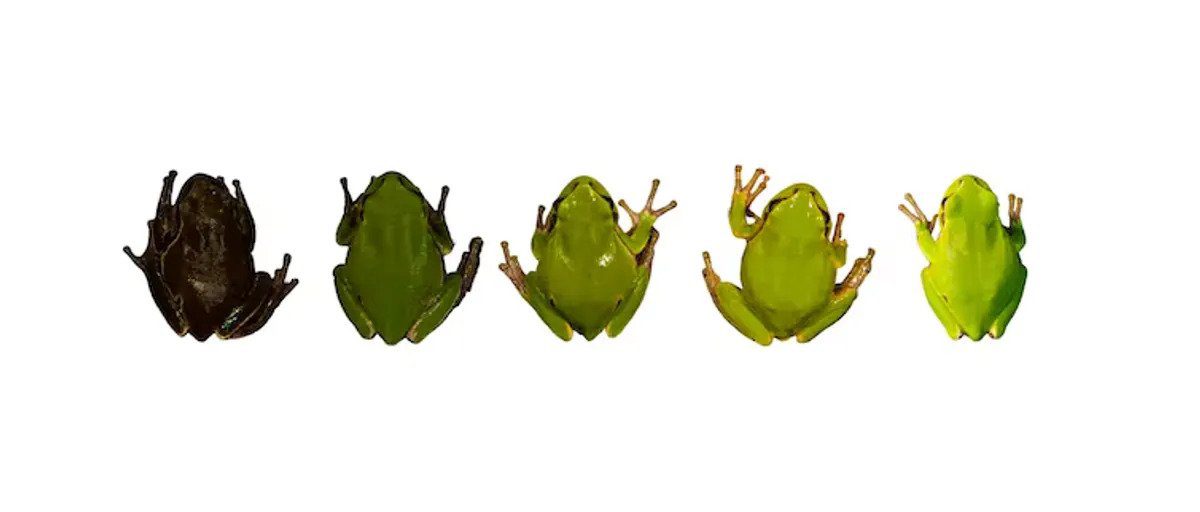

The species is normally a vivid green color, but Chernobyl tree frogs look a little different. Those found in the Exclusion Zone are generally a much darker color – sometimes pitch black.

This stark difference is the result of rapid evolution in response to radiation, the researchers responsible for the discovery believe.

Frogs with a darker color have more melanin, which is known to reduce the effects of ultraviolet, as well as ionizing, radiation. Therefore, darkly colored individuals are less likely to suffer cell damage as a result of radiation exposure and so would have been evolutionarily favored in the aftermath of the accident.

A haven away from humans

For lots of species living in and around Chernobyl, their populations are thriving, in number at least, since the disaster. In fact, Chernobyl is now one of the largest nature reserves in Europe, as well as, possibly, “Europe’s largest experiment in rewilding”.

Today, the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone spans 2,600 square kilometers (1,000 square miles) and is almost void of human life. While the potentially hazardous effects of radiation exposure can’t be denied, some experts argue they pose less of a threat than the potentially hazardous effects of humans.

“Humans have been removed from the system and this greatly overshadows any of those potential radiation effects,” biologist Jim Beasley, who has studied wolves in the Exclusion Zone, told National Geographic back in 2016.

Without humans in the picture, Chernobyl has become a surprising safe haven for all sorts of animals, from deer to wild boar. Wolves, particularly, are thriving: their population density is around seven times higher in the Exclusion Zone than in surrounding reserves.

Wolves seem to be thriving in Chernobyl. Image credit: wildlife_outdoor/Shutterstock.com

One study used camera trap footage to identify 15 different vertebrates, including mice, raccoon dogs, American mink, and Eurasian otters, inside the Exclusion Zone. Tawny owls, jays, magpies, and white-tailed eagles have also been found.

As have beavers, according to National Geographic. “The beaver population is growing,” Marina Shkvyria, of Ukraine’s National Academy of Sciences, said, adding that this will eventually return the land to bog.

“The beaver in Ukraine is exactly like the elephant in Africa: it completely changes the look of the landscape.”

Chernobyl’s Przewalski’s horses

Even endangered wild horses have made their home in the Exclusion Zone, using the abandoned structures as shelters.

Around 30 Przewalski’s horses were introduced into the Exclusion Zone in 1998 in an attempt to rescue the species from extinction. Their population is now believed to be about 150 inside the Exclusion Zone, with another 60 horses over the border in Belarus.

The severe environment of Chernobyl has provided something of a sanctuary for “the last truly wild horse”, as well as reams of other animals that have navigated life here in the wake of nuclear disaster.

Source Link: Curious Creatures Of Chernobyl: The Animals Living In The Shadow Of Nuclear Disaster