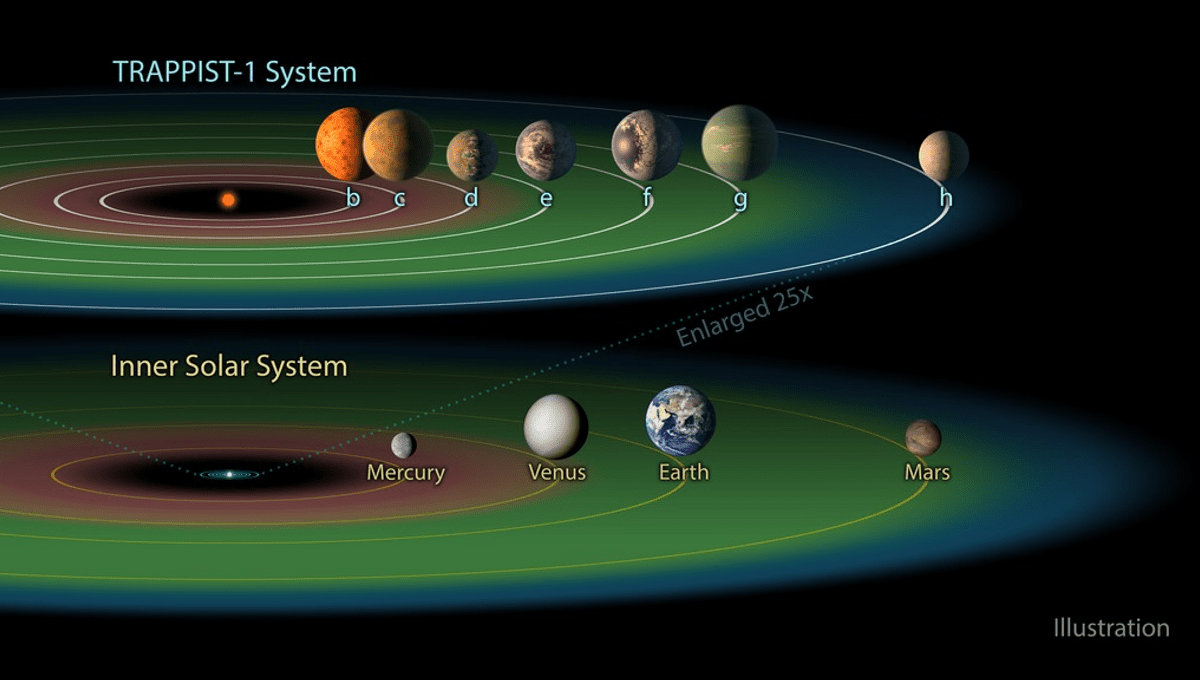

Were it not for the stellar flares, the TRAPPIST-1 star system would look like the perfect place to hunt for life. With three rocky planets in the “habitable zone” where temperatures are right for liquid water, TRAPPIST-1’s worlds have fascinated astrobiologists since their discovery. At just 39 light years from Earth, it is also close enough that telescopes may soon be able to view these planets directly.

There’s just one drawback, however. Like most red dwarfs, TRAPPIST-1 is given to stellar flares proportionally much larger than those on the Sun. TRAPPIST-1 is so faint its habitable zone is very close to the star, leading to fears the flares could sterilize the planets.

A paper in Astrophysical Journal Letters turns this on its head, pointing out that these flares could affect close-in planets’ interiors. If this maintains geological processes that replenish the planets’ atmospheres, it might increase their chances of hosting life. The authors acknowledge more work needs to be done to calculate how the effects balance out but argue we shouldn’t be so quick to write off flarey stars’ systems.

“Plasma bursts and enhanced UV associated with CMEs [coronal mass ejections] and flares can lead to ionization of exospheres and facilitate atmospheric erosion,” the paper notes. This has been extensively studied, and debate rages as to whether such effects would rule out the prospects for life around frequently flaring stars, such as Proxima Centauri.

This is one of the biggest questions we need to answer to predict the state of life in the galaxy. Most currently known candidate planets for hosting life orbit stars like TRAPPIST-1. If these are all airless worlds life will not only be much rarer but separated by such large distances the prospects for meeting are greatly reduced.

However, the authors note, no one has previously considered the electric currents flares like this could induce within planets. Rocky planets like Earth have insulating outer layers, but their interiors are conductive. “Therefore, the magnetic energy carried by an ICME [interplanetary CME] induces currents in the interior,” the authors write.

By modeling the amount of heat released as these currents dissipate, the authors conclude electricity would flow inside planets with plausible compositions whenever the radiation from a flare passes by.

Moreover, while some studies have concluded strong magnetic fields can protect planetary atmospheres from flares (although this is debated), the paper concludes intrinsic magnetic fields make for more internal heating. The combination of strong fields and regular powerful flares could raise inner planets’ mantle temperatures by 1,000 Kelvin.

This greatly increases the chances that TRAPPIST-1’s planets remain internally molten, despite their great age, the authors conclude. Indeed, the approximately 20 TerraWatts released would be similar to the heat produced by radionuclides within the Earth that keeps it hot. This depends, however, on them possessing fields similar in strength to the Earth’s; we currently don’t know if they have magnetic fields at all.

An additional heat source like this could sustain plate tectonics and volcanic eruptions, releasing gases like carbon dioxide. It will take a lot more research to determine whether replenishing the atmosphere in this way would be sufficient to compensate for the loss by flare erosion, and if so under what circumstances.

Planets heated in this way could have intriguing differences from Earth. The paper notes most of the electromagnetic heat would dissipate in the uppermost part of each planet, and no one knows how this would change planetary dynamics compared to radioactive decay occurring nearer the core.

Nevertheless, as in a 60’s revival, it seems flares may be coming back in style.

The Paper is open access at The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

[H/T: Universe Today]

Source Link: Curiously, TRAPPIST-1’s Flares Might Make Its Planets More Suitable For Life