Sabertooth cats might be best known from their apparently social behaviors in movies (looking at you Diego), but evidence from the fossil record suggests that they were known to hunt cooperatively. A new skull fossil of a primitive sabertooth from the Linxia Basin, China, shows cranial adaptations to social behavior, and an injured forepaw reveals direct evidence of partner care.

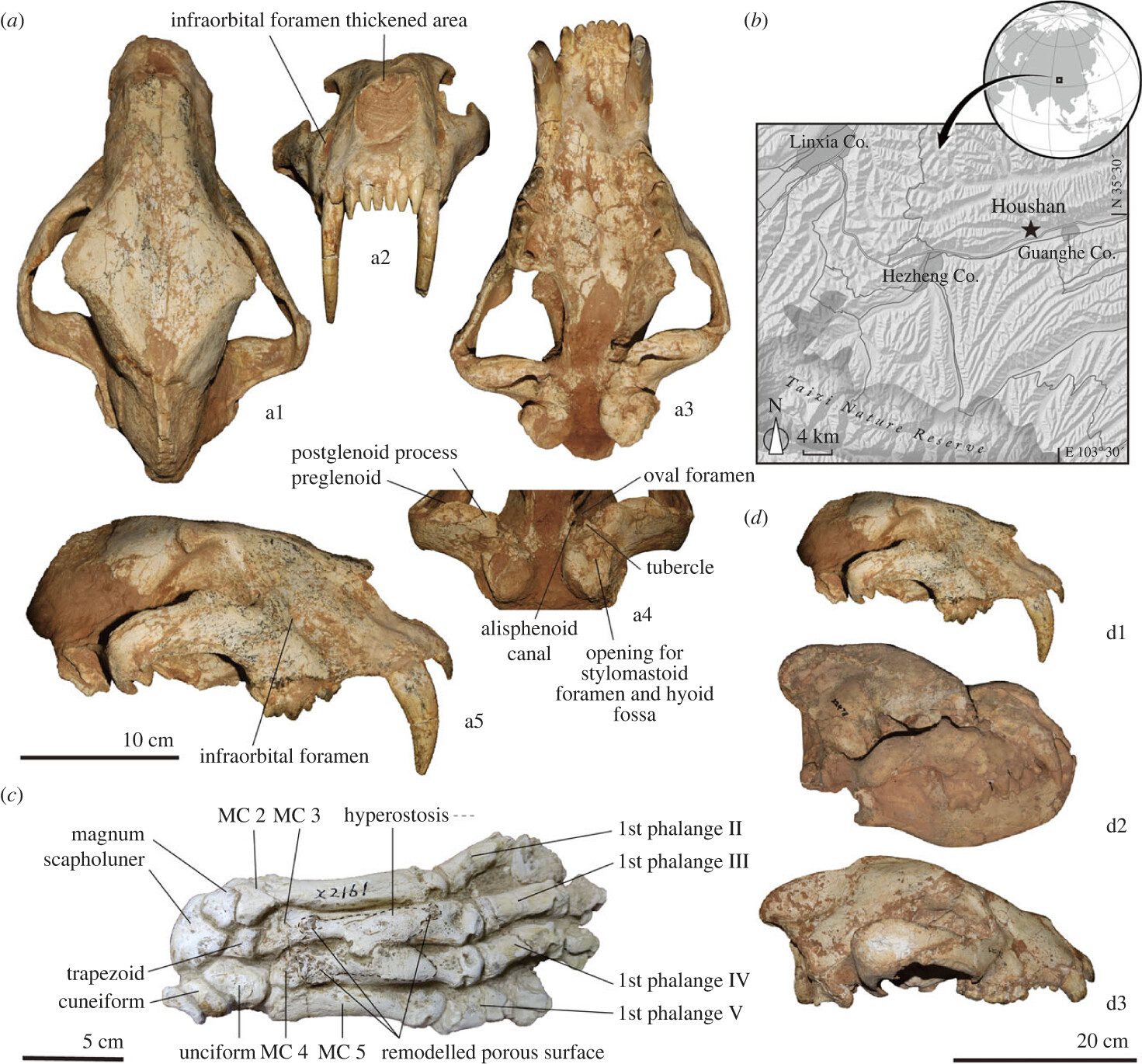

The new skull fossil was found on the northeast border of the Tibetan Plateau. Previously, researchers listed the cranium as belonging to Machairodus palanderi and Amphimachairodus sp., but the skull specimen was never formally scientifically described. The team think that the new cranium shows the typical features of the Amphimachairodus genus, and therefore represents the most primitive member of the genus (A. hezhengensis sp. nov).

The team suggest that the lineage of A. hezhengensis sp. Nov and other Machairodontini originated in Asia, and that the dispersal of this tribe increased quite substantially after the appearance of A. hezhengensis. These sabertooths had adaptations to living in open environments that allowed them to thrive in the dry arid landscape that began spreading across the world. The team suggest that the diversification of this lineage reached its peak in the Miocene, but then rapidly reduced following a large environmental change in the crossover between the Miocene and Pliocene eras.

Modern day species of big cats such as snow leopards (Panthera uncia) and cheetahs (Acinonyx jubatus) are adapted to living in open areas because they possess very wide foreheads that allow for a larger sinus, helping with respiration and acting as a buffer against cold air, and for heat dissipation when running at high speeds. The skull fossil of the sabertooth was also found to have a similar wide forehead, making it equally likely to have been an adaptation for living in an open environment.

Further adaptations to do with the placement of the eyes within the skull show similarities to social species of big cats like lions (Panthera leo). Orbits in the middle of the cranium, like those of lions and the new sabertooth skull, suggest an adaptation for hunting, giving a wider field of view. This is also a trait more associated with social behavior, allowing individuals a better visual field to spot companions and therefore be more successful during cooperative hunting.

The forepaw that was also found in the Linxia Basin is similar in appearance to the forepaw of a small lion or a tiger. The paw fossil shows an injury and subsequent healing, which would have restricted the individual’s ability to run at great speed and capture prey as effectively. The team think that the healing process is so advanced within the fractures of the paw that the sabertooth was able to survive for a long time after the injury occurred.

This evidence of the healed fractures, coupled with the cranial morphology, the benefits of hunting cooperatively in open space, plus the pressure to defend prey from large kleptoparasites, all point to the existence of partner care and social behavior within this species.

The study is published in Proceedings Of The Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

Source Link: Despite Being Perfectly Adapted Hunting Machines, Sabertooth Cats Took Care Of Each Other