Australia’s dingo-proof fence has created a sharp ecological boundary, with some animals flourishing on one side and struggling on the other. Eventually we might expect this to lead to species evolving on separate paths, but new evidence suggests that what was expected to be a slow process might be happening in a matter of decades.

The dingo-proof fence winds its way across more than 5,000 kilometers (3,107 miles) of Australia, forming the world’s longest environmental barrier. Although there are dingoes on both sides, they are far more common to the northwest, providing an outstanding opportunity to observe trophic cascades in action. Many native animals flourish on the one side while facing local extinction just meters away, depending on whether there are sufficient dingoes present to keep invasive foxes, cats, and rabbits under control.

Abundance is one thing, but when a team of researchers investigated differences between red kangaroos living on either side of the fence they found much slower growth among those protected from dingoes. In a new study, they raise the possibility that within just a few decades the kangaroos have evolved not to hurry their growth to get big enough to escape their main predator.

“We did not expect to see that, on average, young animals inside the fence were lighter and smaller than those outside the fence,” Dr Vera Weisbecker of Flinders University said in a statement. Yet that is what the authors found, and to a striking degree.

Red Kangaroos (Osphranter rufus) are the largest surviving Australian terrestrial native species. Little threatens the adults aside from humans and drought, with the possible exception of battles with a fellow member of their own species. However, the young and smaller adult females, are a favorite prey for dingoes.

Consequently, for thousands of years, kangaroos have had the incentive to grow large enough to be safe from dingoes very fast. South-east of the fence, however, all that is required is to be too big for a fox to tackle, after which growth can safely slow down.

Weisbecker told IFLScience that “There are reasons not to grow quickly, for example you can develop better immune systems if you redirect energy there.” Weisbecker added that one possible explanation for what the team found is that the kangaroos have some way of sensing danger and grow more slowly in its absence. That would be a remarkable discovery, but perhaps not totally surprising for a species able to put gestation on pause so its young are born in time to coincide with abundant food.

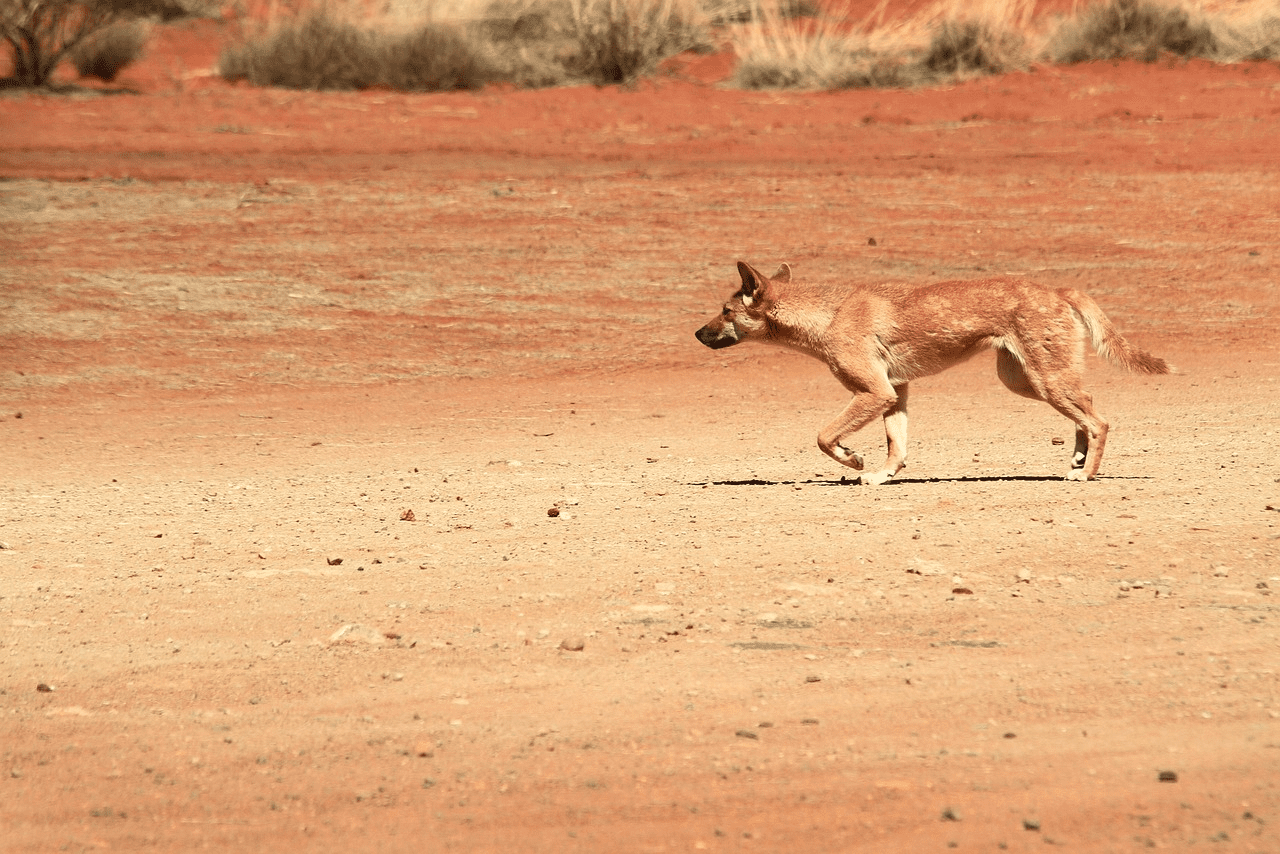

If a pack of these were coming for me, I’d try to grow up fast as well.

Image Credit: Jacqueline Wales, CABAH

Alternatively, the removal of dingoes’ selection pressure on slow growers may have favored those kangaroos genetically programmed for more leisurely growth. That would be an outcome entirely in keeping with Darwin’s work if it took place over centuries. However, while parts of the fence date back more than a hundred years, the area where Weisbecker and co-authors worked has only been effectively divided since the 1970s. Previously, the fence there was in such poor condition that plenty of dingoes got through.

Whether the kangaroos have evolved substantially different growth rates in around 17 generations is “The million dollar question,” Wesibecker told IFLScience. If so, they could be on the path to becoming separate species that have difficulty interbreeding.

Fascinating as this would be to observe, scientists may not get the chance. Growing evidence of the benefits dingoes bring to native animals threatened by foxes is building pressure to remove the fence. However, while it stays, the authors encourage other researchers to use it to explore if similar changes have emerged in other species.

The work was not designed to explore changes in growth rates, as no one expected this to have happened so fast. Instead, the authors were interested in exploring whether differing levels of competition and food abundance had led to noticeable changes in the kangaroos’ skull shapes on either side of the fence. On that score, they could find no difference.

The study is published open access in the Journal of Mammalogy.

Source Link: Dingo-Proof Fence Could Be Driving Astonishingly Fast Kangaroo Evolution