Walking at extreme elevations can lead to fatal altitude sickness, but what happens to people who venture deep into the Earth? Miners and bridge engineers have historically been exposed to atmospheric pressures twice that at the surface, and the toll it took on their bodies was also sometimes fatal. It got us wondering, what does it feel like to venture deep into the Earth? And what’s the opposite of altitude sickness?

The largest-known deposit of rare-earth metals in Europe was discovered by a mining company in Sweden, close to its Kiruna iron ore mine, which is the largest of its kind. Writing for NPR, International Affairs Correspondent Jackie Northam explained what it feels like to make the 30-minute car journey into the iron ore mine’s base.

“Your skin becomes noticeably drier, your ears pop and it’s hard to shake a feeling of isolation as the truck twists and turns on the darkened road, guided only by reflectors on the tunnel’s reinforced gray, stone walls. When you finally reach the bottom, more than 4,000 feet [1,219 meters] beneath Earth’s surface, you discover a complex of brightly lit offices, a cafeteria and even a car wash.”

The symptoms might sound familiar to anyone who’s ever been on a plane, except that one mode of transportation is taking you very high into the sky, while the other is plummeting into the ground. In a 2008 paper, scientists describe how the deepest levels below the Earth’s surface where humans have set food are the depths of the deepest mines.

The deepest of them is the Mponeng Gold Mine, formerly known as the Western Deep gold mine, which is in Johannesburg, South Africa. According to the Guinness World Records, “By 2012, the operating depth had already reached 3.9 km [2.4 miles] below the surface, and later expansions have resulted in digging below the 4 km [2.5 mile] mark.”

At this depth, miners are battling with blistering temperatures that rapidly increase with depth. The rock walls reach 60°C (140°F), and humidity can exceed 95 percent, but mitigators like ice slurry and ventilation are used to lower this to a tolerable level. But what about the pressure?

Many deaths occurred during the construction of the Brooklyn Bridge in New York, US, but among them was “caisson disease”, now known as the bends. You may be thinking, “Isn’t that a diving illness?”, but actually the first cases were diagnosed in miners and bridge builders.

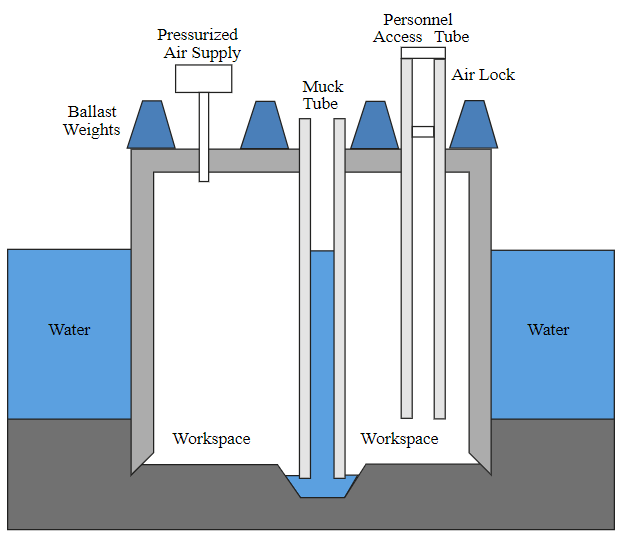

Humans building bridges have to work in pressurized air so that sediments can be dug out without water rushing in.

The deaths in Brooklyn were seen among the “sandhogs” who worked at double the pressure seen at the surface because compressed air was used to prevent river water from entering the construction site, explains History.com. As sandhogs dug deeper, they experienced worsening symptoms including muscular paralysis, slurred speech, joint pain, and stomach cramps.

The debilitating symptoms were first known as caisson disease because the people getting it were digging inside chambers of the same name that were plunged deep into the East River. They were a crucial part of the bridge’s construction as sediment was dug out of the caissons until the empty shaft was eventually filled with concrete, but it turned out they weren’t a safe place to work when three construction workers died of the bends in quick succession.

The bends, or barotrauma, is caused by moving from a place of high pressure to a place of low pressure in a short space of time. For this reason, it’s also known as decompression sickness, and today it most commonly affects divers, aviators, astronauts, and people working in compressed air (such as those involved in the horrifying Byford Dolphin Accident).

Moving from an area of high pressure, like the deepest depths of a mine, to an area of low pressure, like the surface, can produce nitrogen gas bubbles in the body. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, where this becomes a problem is when that pressure change is made too quickly, releasing the gas into the body. “This can be very painful and sometimes fatal,” they say.

Common symptoms of the bends include joint pain, bone destruction, pink marbling of the skin, stroke, paralysis, shortness of breath, and arterial gas embolism, which is when gas bubbles block the flow of blood. The good news is that if the condition is diagnosed soon enough, it can be treated using a decompression chamber. This effectively recreates the slow movement from one pressure state to another, unlike the sudden change that brought on the bends to begin with.

It seems that barotrauma is more considerable a threat to people working in compressed air than miners, as the review “Barometric Hazards Within The Context Of Deep-Level Mining,” concluded that “Present knowledge indicates that pressure-related effects on mineworkers’ health would be moderate and limited to individuals with predisposing medical conditions, of which chronic cases could be identified through risk-based medical examinations and then managed, while acute conditions could either be prevented through prophylaxis or treated symptomatically.”

So, while you may feel a little odd descending into Sweden’s Kiruna iron ore mine, your chances of significant injury are pretty slim. Then again, there’s always mine spiders to worry about.

Source Link: Does Going Deep Into The Earth Make You Unwell Like Altitude Sickness?