It’s literally the oldest trick in the book, although it’s one you’ve probably never seen before. And while no beautiful assistants are sawn in half, this ancient illusion – performed for the Egyptian Pharaoh Khufu – is death-defying in the truest sense of the word.

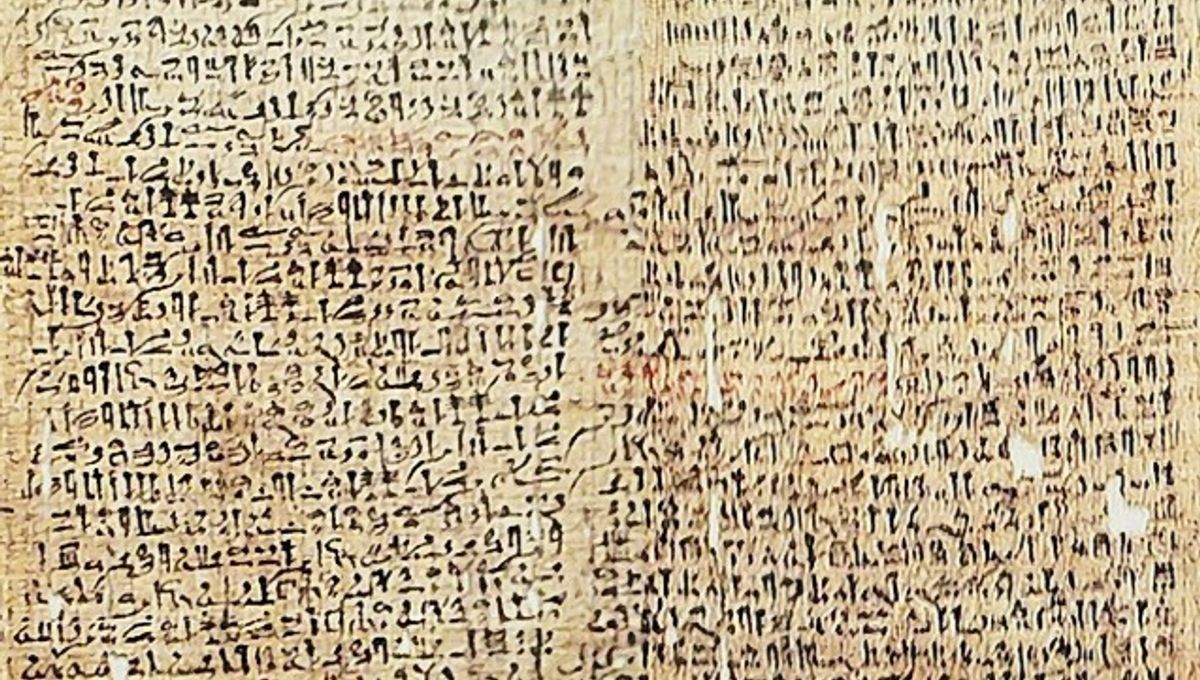

Long before the rabbit-in-the-hat trick was even conceived, an unknown Egyptian scribe penned what is now known as the Westcar Papyrus. Thought to have been written during the Second Intermediate Period – which lasted from 1782 to 1550 BCE – the scroll recounts a series of tales that take place about a millennium earlier, when Khufu ruled over the Old Kingdom and built the Great Pyramid at Giza.

Consisting of five short stories, the Westcar Papyrus records a number of encounters between the Pharaoh and several of his heirs. In the fourth of these, Khufu’s son Hardedef introduces the king to a magician named Djedi, who is said to be 110 years old and claims to drink 100 jars of beer a day.

Yet Djedi’s heavyweight drinking is far from his most impressive attribute, and the sorcerer is in fact famed for his supposed ability to reattach a severed head, bringing the decapitated back to life. Eager to witness the trick, Khufu sends for a prisoner to “volunteer”, although Djedi refuses to perform the miracle on a human being, instead demonstrating his abilities on a goose.

According to the papyrus, the bird’s head was removed, at which point “Djedi said his magic spell, and the goose stood up waddling” as its head reunited with its body. At Khufu’s request, the trick was then repeated on another goose, then on a different water bird, and finally on a bull.

Each time, the decapitated animal rose and retrieved its head, which was then magically reattached.

Wonderful as this may seem, however, the text is entirely fictional, and no such wizardry was ever performed. In fact, it’s unlikely that Djedi ever even existed, and while magic tricks are likely to have been around for thousands of years, there’s no solid evidence that any were mastered or performed by the Ancient Egyptians.

The closest hint of any sleight-of-hand by banks of the Nile comes from the tomb of a royal official named Baqet III, who lived during the 21st century BCE. Among the illustrations on the tomb is a picture of two men handling a series of bowls, which some people claim is the earliest depiction of the famous cup-and-ball trick, whereby a magician causes a ball to disappear, multiply, or teleport between cups.

However, this interpretation is highly debatable, and many scholars believe the illustration actually portrays the two men playing a game or engaging in some other unknown – yet definitely not magical – activity.

In fact, the earliest solid evidence for this particular trick appears in Roman times, when the philosopher Seneca the Younger wrote about “the juggler’s cup and dice” in his Moral Letters to Lucilius in 65 CE. Not wanting to deceive or hoax anyone, then, we should probably say that these Roman tricksters were the first magicians, although the decapitated goose trick still holds the record for the earliest mention of a conjuring magic trick.

Like magic? Join us for the CURIOUS Live Christmas Special as we speak to magician and psychologist Dr Gustav Kuhn about The Science Of Magic. From the psychology of a good trick to how magic can be used as a tool to tackle cybercriminals and understand the placebo effect, there are all kinds of ways magic and science intersect, and Kuhn will be joining us for the watch party at 3 PM GMT/10 AM ET to answer your questions. Click here for more information.

Source Link: Does This Ancient Egyptian Scroll Recount The World’s Oldest Magic Trick?