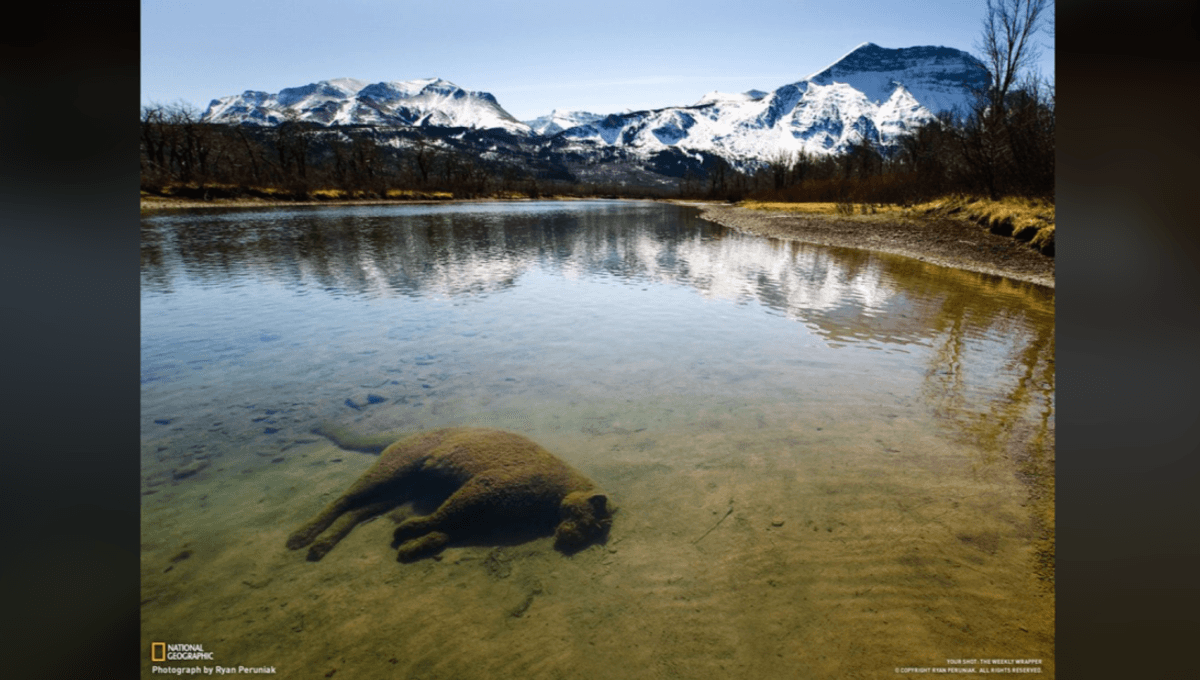

A beautiful photograph of a cougar that met its end at the bottom of a lake shows the remarkably intact animal covered in a fluffy layer of algae and sediment. Look online and you’ll find many people debating the origins of the photograph, in some cases stating it shows the early stages of fossilization, while others have – wrongly – argued it’s really a kangaroo.

ADVERTISEMENT

What’s really going on? We spoke to Park Ranger and photographer Ryan Peruniak, who actually took the photo, to find out.

The cougar was in such a peaceful pose on the riverbed, just like you might find your house cat sleeping in the sun

Ryan Peruniak

“I was walking along the riverbank one spring after the ice had melted off and saw the cougar lying on the bottom, covered in a layer of algae and sediment,” he told IFLScience. “It was such a unique scene that I had to get a photo of it. The cougar was in such a peaceful pose on the riverbed, just like you might find your house cat sleeping in the sun.”

Securing the shot took dedication as Peruniak had had to wade into the icy water up to his waist to capture the cougar with the mountains in the background. Just a brief glimpse into the kinds of places wildlife photographers find themselves when trying to secure the perfect shot, and an insight into what probably led to this cougar’s demise.

ADVERTISEMENT

“The cougar most likely fell through the ice when it was crossing the river earlier in the winter,” said Peruniak. “I am a Park Ranger in Waterton Lakes National Park, and this is the third cougar I’ve found dead in a lake or river.”

“Cougars can swim, and have sharp claws, so one would think they’d be able to rescue themselves if they fall through the ice, but that does not seem to always be the case.”

Is the cougar becoming a fossil?

One Facebook post suggests that if left to its own devices, the sediment-coated cougar will begin a sequence of natural processes that could eventually lead to fossilization. It’s a nice idea, but one that reality didn’t allow for in this particular circumstance.

Unfortunately, people like to collect the skulls and claws of animals like cougars

Ryan Peruniak

“Unfortunately, people like to collect the skulls and claws of animals like cougars, and this particular cougar was in a location where it was likely to be found by someone else, so we removed it from the river and disposed of the carcass in a less obvious location,” Peruniak explained.

But what if, say, it had been possible to leave the cougar where it lay? Could humans in a few thousand years have enjoyed a remarkably intact cougar fossil? It’s an interesting question, and one that we can explore theoretically.

What makes a fossil?

For something to be considered a fossil, the British Geological Survey states it needs to be at least 10,000 years old, but the actual process of fossilization can begin much faster than that. In fact, in an experiment that looked at frog remains, it was observed that fossilization was occurring in certain organs within just two years.

The fossilization process is a very rare process

Dr Susannah Maidment

One thing that significantly influenced the speed at which this process began for the amphibians was the presence of microbial mats. These biofilms created a kind of sarcophagus that both preserved the frogs’ soft tissues and sped up the rate of fossilization. However, an icy lake is likely to slow down microbial activity, making this kind of preservation less likely – although not impossible.

The decomposition ecosystem

We know the lake was at one time frozen, and will freeze again, which could provide the crucial barrier needed to get really detailed fossils with soft tissues intact. As Dr Susannah Maidment of the Natural History Museum, London, told IFLScience, fossilization itself is rare and it really all comes down to fighting off the many agents of decomposition to be found in the environment.

“For the vast majority of animals that have ever lived, even their hard parts don’t remain. The fossilization process is a very rare process,” Dr Maidment, a senior researcher in the division of Vertebrates, Anthropology, and Palaeobiology, told IFLScience. “Sometimes we have things like skin and other soft tissues like feathers preserved and usually that requires a quite unique set of burial conditions, often very rapid burial.”

ADVERTISEMENT

“If you imagine that your dinosaur dies on a flood plain, something like the Serengeti, and it sort of keels over and dies, then all these other animals are going to be coming along and tearing it apart. You’ve got your vultures picking away at it, and lions taking bits, then bacteria breaking it down, and it’s all going to get dragged all over the floodplain.”

“What we need, really, is to take that dead carcass and the moment it dies, is to put it somewhere where that scavenging process and that rotting process can’t occur. A really good way is to bury it really, really rapidly. So, sometimes these animals fall into lakes or are overcome by sand dunes, and that’s what we need for soft parts to be preserved.”

Our unlucky cougar seems to be about 10,000 years short of true fossil status, then, but Peruniak has enjoyed the rounds of debate stirred up by his photograph all the same.

“It’s an honour to have one of my images garner such repeated attention,” he said. “The strongest images are thought provoking, and this one seems to really resonate with a lot of people in a way I couldn’t have imagined when I was taking the photo.”

ADVERTISEMENT

The photo is a poignant reminder of the sophisticated mechanisms that exist in nature to decompose the dead so that we’re not wading in carcasses, and what can happen when a barrier like an icy lake prevents them from getting to work. The same decomposition ecosystem that comes for animal remains is seen in corpses, and there scientists have noticed a curious connection that unites human remains buried in different locations.

Source Link: Does This Photo Show A Cougar Submerged In Sediment Beginning Its Fossilization Journey?