As sea ice melts, it creates feedback that warms the Earth. New research shows that feedback is happening faster than previously estimated. As a result, there has been a 13-15 percent reduction in the cooling effect of global sea ice since the early 1980s, more than the loss of ice itself.

Ice plays an essential role in keeping the world cool, because it is so bright. Open water and bare rock absorb a lot of the solar radiation falling on them, but ice and snow reflect most of it. Even though some of the reflected photons are captured in the atmosphere, many escape to space.

Climate scientists have known for over a century that the loss of ice could create a vicious circle that would cause the planet to heat up, and for decades have been aware that this is happening. To assess the size of this change, however, we need to do more than measure the total extent of ice and see how it has changed. A more sophisticated analysis reveals changes at both poles over the last four decades have had more impact than a simple analysis might predict.

“When we use climate simulations to quantify how melting sea ice affects climate, we typically simulate a full century before we have an answer,” said Professor Mark Flanner of the University of Michigan in a statement. “We’re now reaching the point where we have a long enough record of satellite data to estimate the sea ice climate feedback with measurements.”

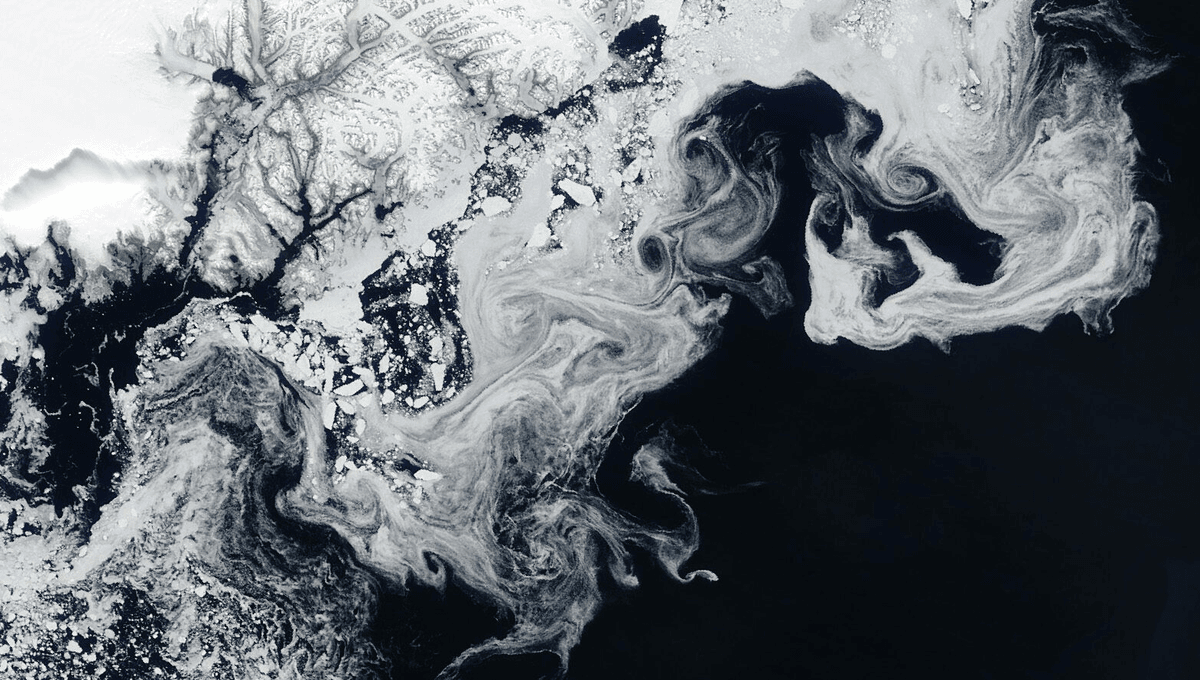

Flanner and colleagues note that as ice starts to warm up, ponds form on its surface. Individually, these are small enough that they’re still included as part of the ice coverage in satellite images. However, they are not as reflective as the ice itself, undermining contributions to keeping the temperature stable. Since the ponds form at times when the ice is in almost continuous daylight, the effect can be quite substantial, summed over enough of them.

More complicated consequences include changes to cloud cover caused by what is occurring at the ocean surface. Even the grain size of snow resting on the ice can alter reflectivity.

Hints that Arctic sea ice might be shrinking were observed before we had the capacity to conduct large-scale observations. Since 1979, satellites have given us that power. Although observations bounce around from year to year, on a longer timespan these have shown a steady decline in sea ice in the Northern Hemisphere. At the peak of summer, this decline now exceeds 40 percent, but it’s smaller at other times of the year.

Nevertheless, Fuller and colleagues calculate the Arctic sea ice cooling effect is down by 21-27 percent since 1980. More disturbing still, most of this decline occurred since 2016.

In contrast, until 2016, Antarctic sea ice was fairly stable, a point climate change deniers were fond of raising. Since then, however, it has shown similarly dramatic declines to the north, leading to easily the lowest ice levels in history last year. This trend is so recent it has not previously been incorporated into assessments of the consequences of warming, but Fuller and colleagues calculate Antarctic ice cooling has fallen by 12 percent in seven years.

“The changes to Antarctic sea ice since 2016 boost the warming feedback from sea ice loss by 40 percent. By not accounting for this change in the radiative effect of sea ice in Antarctica, we could be missing a considerable part of the total global energy absorption,” said University of Michigan doctoral student Alisher Duspayev. Duspayev is first author of a reassessment of the warming consequences of the observed ice loss, using satellite measurements of reflected radiation.

In addition to publishing a paper on the current state of warming feedback, Duspayev, Flanner and colleagues are establishing a website that will track the situation using frequently updated satellite data.

The study is published open access in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Source Link: Earth's Poles’ Cooling Power Is Declining Even Faster Than Their Ice Coverage