In the 19th Century palaeontologists collected many bones and teeth they couldn’t identify. Some of these came from rich Ethiopian deposits laid down up to 4.5 million years ago. Now, after 150-180 years in storage, some of these fossils have been identified as coming from giant otters that weighed more than 200 kilograms (440 pounds) and co-existed in the area with our ancestors.

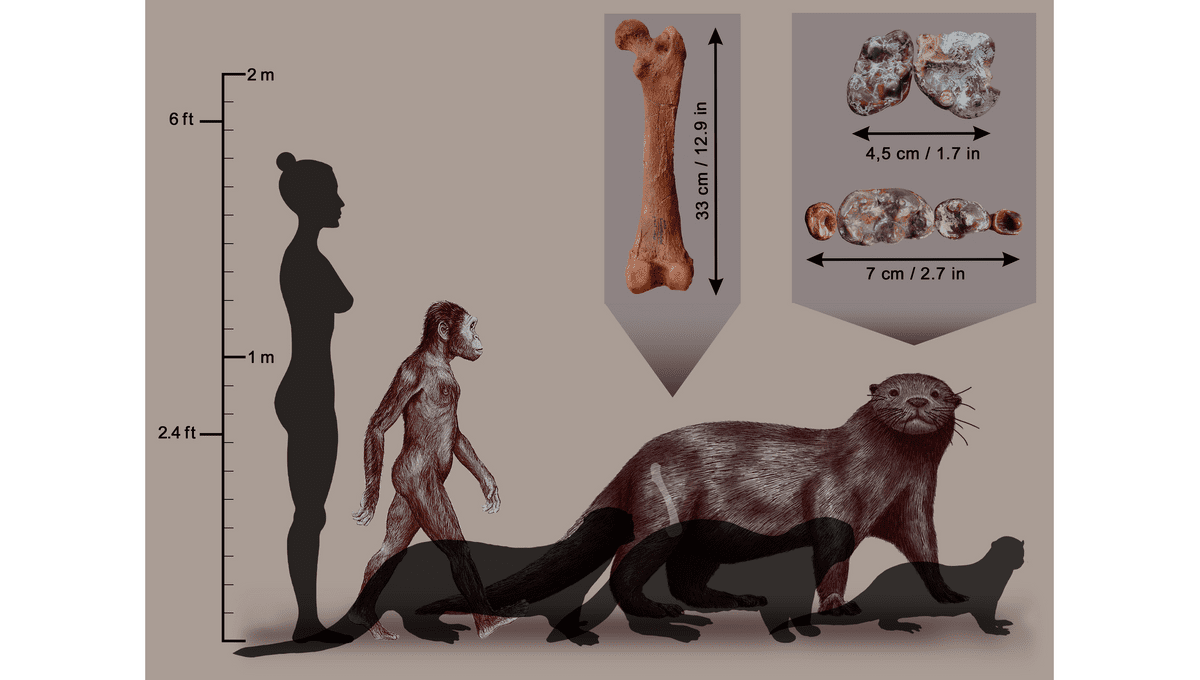

The new species took so long to identify because we are a very long way from having a complete skeleton. A paper in the French journal Comptes Rendus Palevol puts together two partial jawbones, a few teeth, and a leg bone to describe a new species the authors named Enhydriodon omoensis, while allocating other scattered otter bones found at the same location to the Torolutra genus.

Giant otters are a long-established feature of the Pliocene and late Miocene Eras. Enhydriodon dikikae, a resident of Africa’s Afar region, was already described as lion-sized when it was scientifically described in 2011, but E. omoensis is larger still.

The most familiar of the 13 surviving otters might be Eurasian otters, but the subfamily covers a surprising range of sizes. Eurasian otters typically weigh up to 17 kilograms (37.5 pounds) but the Asia small-clawed otter weighs just 2-6 kilograms (4.4 – 13.2 pounds), while the North Pacific sea otter can reach a hefty 45 kilograms (99.2 pounds).

The extinct Enhydriodon genus has been found in many locations across eastern Africa and sometimes beyond, with at least six species living in the eastern rift system. E. omoensis was found in the Lower Omo Valley, Ethiopia north of Lake Turkana where the oldest stone tools were made 3.3 million years ago.

Australopithecine fossils have been found in the same Omo formation, and subsequently early humans lived in the area as well; Homo Sapiens may even have evolved there. E. omoensis would have been a competitor with Australopithecines for food, and perhaps the first humans if it survived a little longer, even if it didn’t eat them directly.

Moreover, this wasn’t one scary beast our ancestors could avoid by staying out of the water.

“The peculiar thing, in addition to its massive size, is that [isotopes] in its teeth suggest it was not aquatic, like all modern otters,” said Dr Kevin Uno of Columbia University in a statement. “We found it had a diet of terrestrial animals.”

The conclusion draws on the fact that plants store different ratios of carbon isotopes depending on their growing conditions and photosynthetic pathways. Herbivores incorporate the ratios of the plants they feed on, which in turn go into the making of carnivores, including their bones and teeth.

Uno and co-authors are confident other bones found in the same formation belong to the Torolutra genus, which resembled the modern river otters and lived mostly on fish. They also describe a bone fragment they believe came from a large Enhydriodon, but can’t identify the species.

Source Link: Ethiopia Once Had Otters The Size Of Lions