With pages that wouldn’t look out of place in a J. R. R. Tolkien novel, the Voynich manuscript is a roughly 500-year-old book filled with puzzling illustrations and writing in a seemingly indecipherable language.

Named after Wilfrid Voynich, an antique bookseller who purchased the manuscript in 1912, the meaning behind the approximately 240 pages remains a mystery to this day, despite many claiming to have unlocked its secrets.

Deciphering the manuscript

Speculation about the book’s origins is vast and varied, with some believing it to be a hoax, that it’s a guide to alchemy, or even that it was written by an alien stranded on Earth. As of yet, none of these claims have been proven, but the efforts to decode the book’s alien language continue.

As the script doesn’t appear to follow any existing language pattern, some have assumed that each character is a symbol as opposed to a letter. The potentially coded language alludes to a theory that the content of the book was intended to remain a secret.

An effort to decode the text using AI in 2018 resulted in the conclusion that the words were likely Hebrew, and that the words were alphagrams: anagrams with the letters arranged alphabetically. Relying on Google translate to understand the Hebrew language, the researchers failed to gather any meaning from the mostly nonsensical sentences, instead just identifying singular words that related to the images seen on the page.

Another theory is presented in a 2019 study that proposes the document was written by and for women, and that this would explain the failure of previous attempts to understand the text. Study author Dr Gerard Cheshire claims that the language isn’t coded at all and is instead written in a proto-Romance dialect, from which many modern European languages originated.

This conclusion, however, came under criticism from other Voynich scholars, who claimed Cheshire fit his findings to his theory by assuming proto-Romance language based on identifying singular words rather than full sentences.

Inside the manuscript

The roughly A5-size book is bound in what’s been described as a renaissance version of a paperback, with some believing its blank cover to be a way of concealing its cryptic content. In one of history’s more gruesome (but not entirely uncommon) practices, the manuscript’s pages are made of the skin of at least 14 full cows.

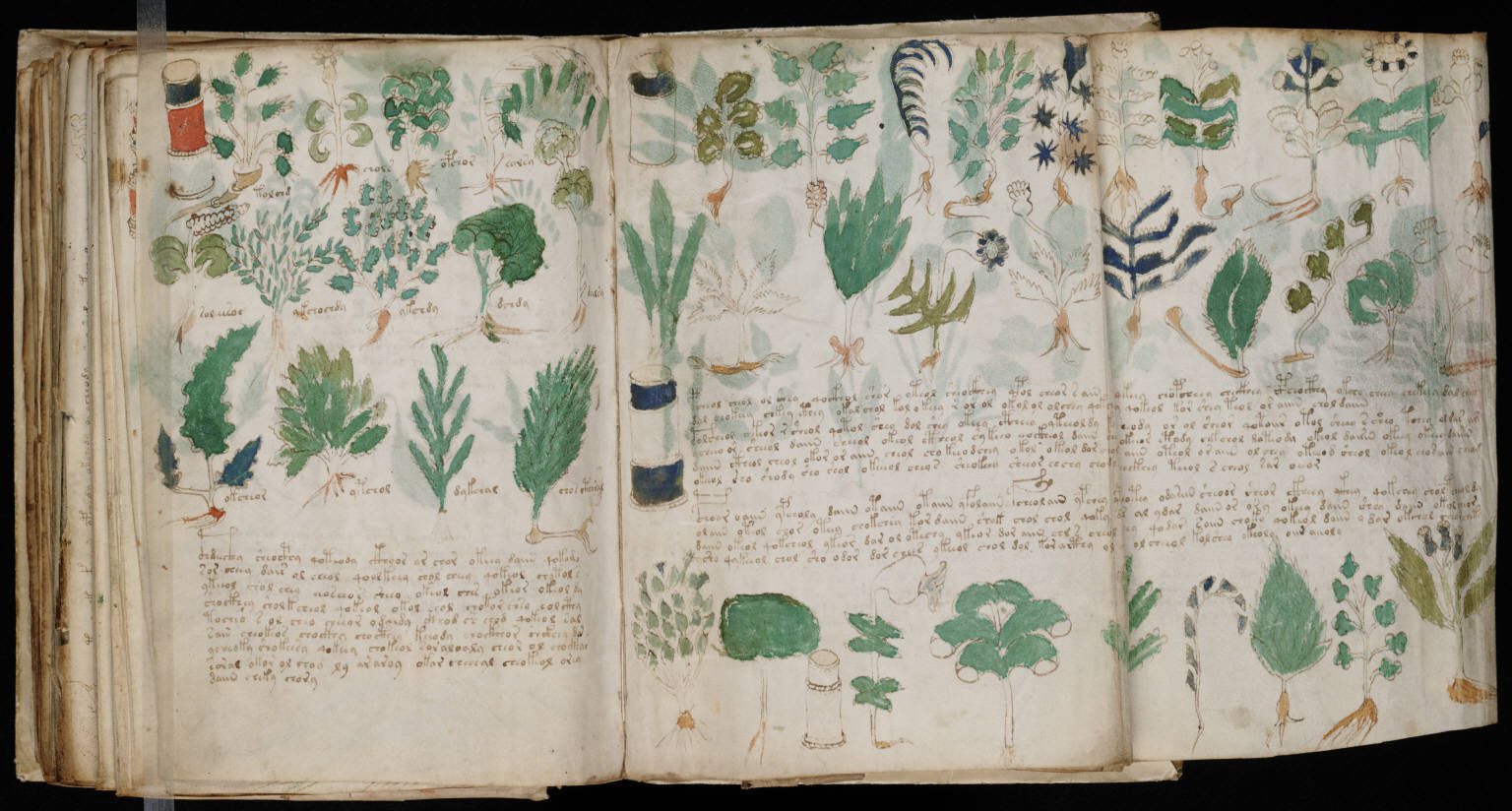

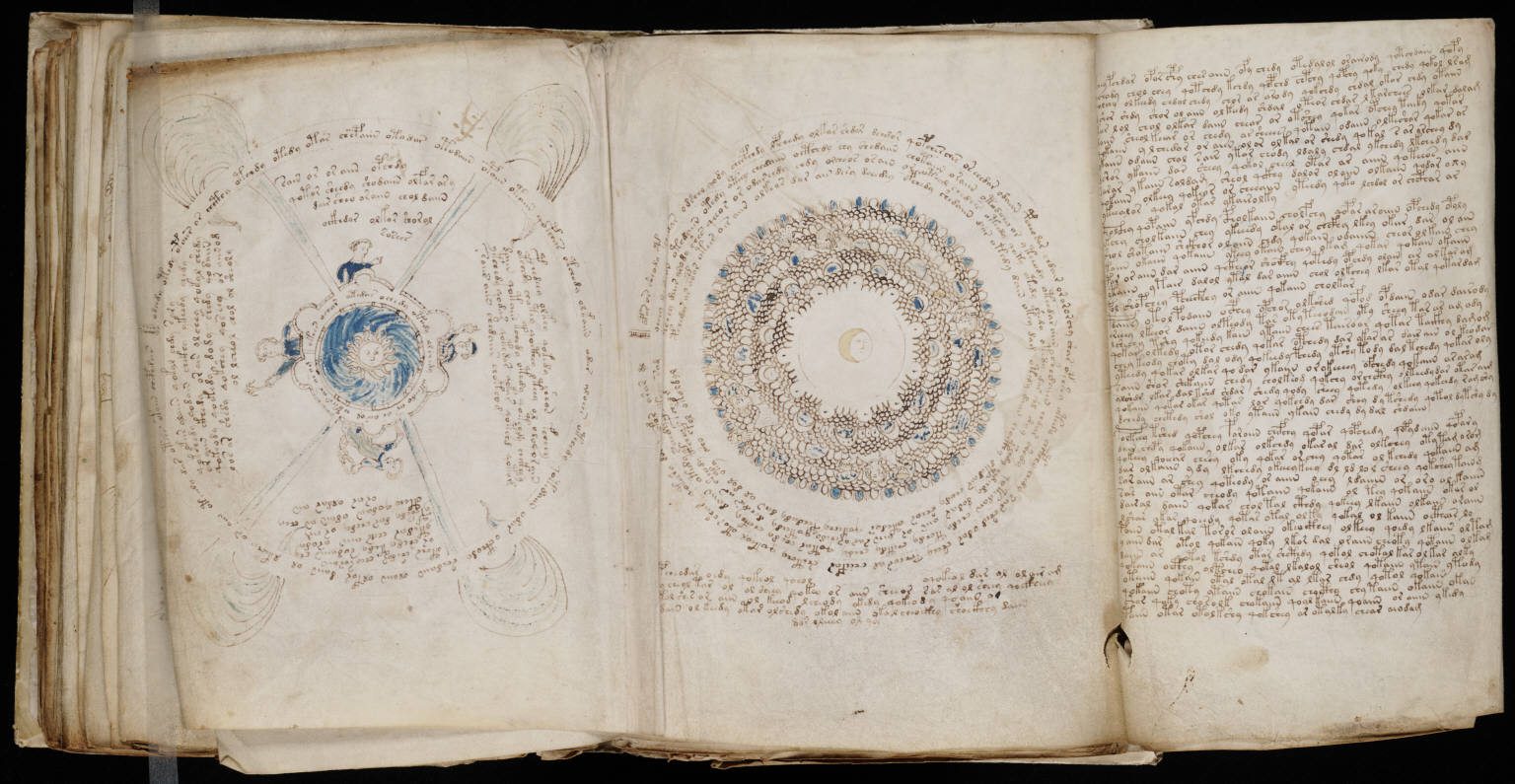

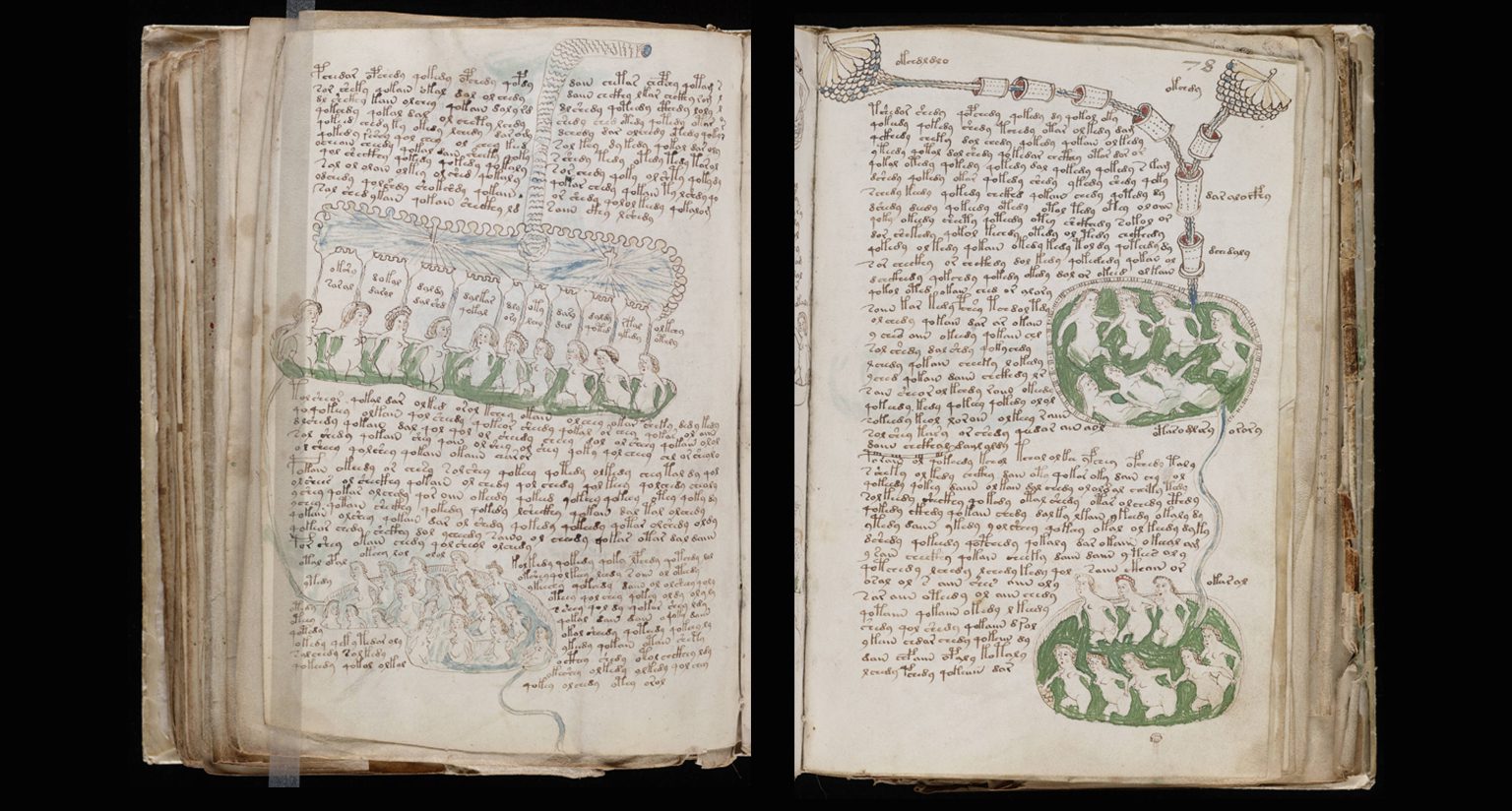

While the language presented in the book has yet to be decoded, the many colorful illustrations seem to separate the manuscript into six distinct sections: botany, astronomy and astrology, biology, cosmology, pharmaceutical, and full pages of text that are thought to be recipes.

Image credit: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University / Wikicommons

The botany section, the largest “chapter” in the book, features 113 detailed drawings of seemingly unrecognizable plant species, while the astronomy and astrology pages show planet arrangements and pictures appearing to depict the different zodiac signs.

Image credit: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University / Wikicommons

Also pictured are illustrations of women bathing in colorful liquids, sometimes appearing intertwined and connected by pipes. This biology section of the book sparked a brief conclusion in 2017 that the manuscript was discussing women’s health, but this theory was quickly debunked.

Image credit: Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Yale University / Wikkicommons

The manuscript’s history

The elaborate history behind the book begins sometime in 15th-century Europe. Believed to have first been owned by Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II of Germany during his reign between 1576 and 1611, the manuscript was said by some reports to have been bought from John Dee for 600 ducats.

Dee, a mathematician and astronomer, supposedly owned the manuscript as a part of a collection of work by 13th-century English philosopher Roger Bacon.

According to sources, the book was believed by some – including Rudolf II – to have been written by Bacon, but radiocarbon dating refuted this claim by placing the production of the book roughly 300 years after Bacon’s death in 1292.

Next, the book was seemingly given by Rudolf II to the emperor’s personal doctor, Jacobus Horcicky de Tepenecz. This assumption comes as the book was studied under ultraviolet light; a message can be seen on a page of the manuscript that reads “Jacobi de Tepenecz.”

The next known exchange comes in 1666 when, just a year before his death, bohemian doctor Johannes Marcus Marci of Cronland passed the book to German Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher.

In the Jesuit College near Rome is where Wilfrid Voynich found the book 246 years later. After Voynich’s death in 1930, the manuscript was purchased from his estate by book dealer Hans P. Kraus, who donated it to Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University in 1969.

Since its arrival at the Yale library, the manuscript has left only once for an exhibit at the Folger Shakespeare Library.

While the original book remains under lock and key, the library does have a true-to-life printed replica on display and open to the public. Printed versions of the manuscript are also available to purchase online if you fancy having a go at deciphering its mysterious ramblings.

Source Link: Everything We Know About The Mysterious Voynich Manuscript