For the first time, the distinctive double peaks in emission lines detected from the heart of a galaxy have given us a chance to explore the edges of the bright disk surrounding the central black hole. This has not only confirmed many things we suspected about the region around supermassive black holes, but also allowed measurements of the disk and the hole itself.

Supermassive black holes and the material spiraling into them, known as accretion disks, shape their galaxies – but most of what we know about them relies on modeling, rather than direct observations. There’s too much obstruction between Earth and the center of our galaxy to see the disk there clearly, despite the dramatic advances made by the Event Horizon Telescope. Meanwhile, other galaxies are so far away we can’t resolve their disks sufficiently to determine their boundaries, let alone what is happening at the outer edges.

At least, that was what astronomers thought, until observations of the galaxy III Zw 002 turned up considerably more than expected. The spectrum observed coming from this galaxy a billion light years from us has allowed Brazilian astronomers to measure the size of the accretion disk around a supermassive black hole for the first time. They’ve also managed to determine its orientation to Earth and a little about how elements are distributed.

As with stars, Active Galactic Nuclei (AGNs), the bright regions around black holes, produce light across the electromagnetic spectrum from their heat, and have greater intensity at specific wavelengths, known as emission lines. Emission lines are the result of electrons, previously energized into an excited state, dropping back to a lower energy level.

When released, each emission line is specific to a particular wavelength of light, distinctive to the energy gap the electron has fallen, which in turn is unique to the element the electron orbits. However, when the source moves rapidly towards or away from us, the wavelength gets shifted.

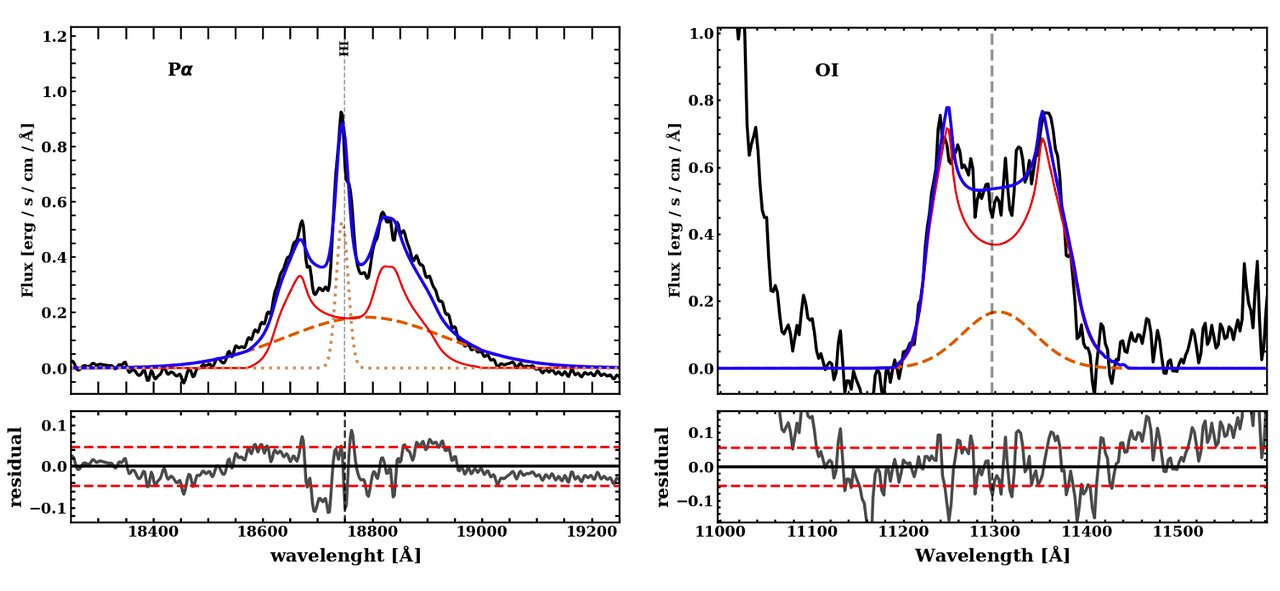

Gasses move so fast around a rotating supermassive black hole that emission lines from one side are seen at slightly longer wavelengths caused by the movement away, while those from the other side appear to be slightly shorter than their true wavelength. This creates what is known as a double peak on either side of the emission line’s normal value.

The light detected from III Zw 002’s nucleus at the Paschen-alpha and Oxygen I emission lines. Notably, the Paschen-alpha line contains a sharp peak at its rest-frame value, whereas the oxygen does not. The difference reflects the radii from which they are primarily emitted

Image Credit: Dias dos Santos et al.

Until now, such double peaks had only been seen for hydrogen emissions in visible light. However, when studying III Zw 002’s light using the Gemini Near-Infrared Spectrograph, Denimara Dias dos Santos was surprised to see one from oxygen, as well as an infrared double-peak from the Paschen-alpha hydrogen line. Dias dos Santos, a PhD student at the Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais, concludes these emissions come from an area spanning 18.8 light-days from the center of the galaxy’s supermassive black hole. The Paschen-alpha line originates slightly further in, at a radius of 16.8 light-days.

By comparison, Voyager 1, the most distant human-made object from the Sun, is at a distance of not quite one light-day.

The disk as a whole, however, probably extends much further. Dias dos Santos and colleagues estimate the region producing emissions extends to 52.4 light-days. It’s the first reasonably precise observational estimate for the size of such a disk. That’s not a distance that is easy to make comparisons for, being more than 30 times beyond the orbits of even the outermost Kuiper Belt Objects like “FarFarOut”, but also less than a thirtieth of the way to the Sun’s nearest neighboring star.

“We didn’t know previously that III Zw 002 had this double peaked profile, but when we reduced the data we saw the double peak very clearly,” said team leader Dr Alberto Rodriguez-Ardila in a statement. “In fact, we reduced the data many times thinking it could be a mistake, but every time we saw the same exciting result.”

“For the first time, the detection of such double peaked profiles puts firm constraints on the geometry of a region that is otherwise not possible to resolve,” Rodriguez-Ardila added.

Assuming the gases’ motion is driven by the black hole’s gravity, the team estimates its mass is 400-900 million times that of the Sun and the disk has an orientation of 18 degrees to Earth.

The study is published open access in The Astrophysical Journal Letters

Source Link: First Emission Lines From The Outskirts Of A Supermassive Black Hole’s Accretion Disk