The Ethiopian wolf (Canis simensis) is one of the most endangered carnivore species in Africa. There are thought to be only around 500 individuals left in scattered populations across Ethiopia’s Bale and Simien mountains. Until now, the entry of the Ethiopian wolf into Ethiopia from Eurasia has not been known from the Pleistocene fossil record, but a new discovery represents the only fossil of an Ethiopian wolf, and sheds light on their likely arrival into this area.

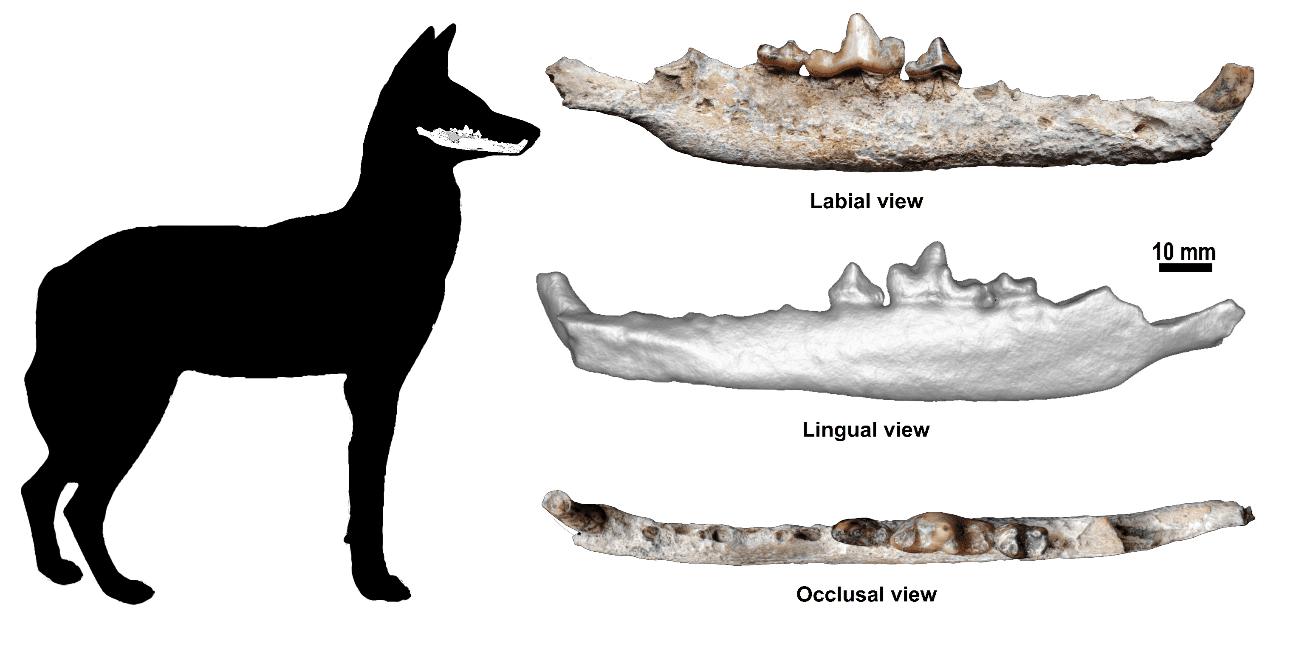

In 2017 a right jawbone was found in the Melka Wakena site-complex around 2,300 meters (7,546 feet) above sea level. Recovered in layers of volcanic ash dating back to 1.5 million years ago, the fossil was initially labeled as an unknown dog species. This find represents the first and only Pleistocene fossil of this species and challenges previous assumptions that species arrived only 20,000 years ago.

This is the only known Ethiopian wolf fossil.

The fossil, known as MW5-B208, bears more resemblance to the Ethiopian wolf than to other living African dog species, such as African hunting dogs and jackals. The spaces between the teeth, for example, are similar between the fossil and extant Ethiopian wolves. By comparing the jawbone with three living species of jackal and the Ethiopian wolf, analysis revealed that the Melka Wakena fossil is that of an Ethiopian wolf.

This finding represents the first-ever evidence that Ethiopian wolves were present in the Ethiopian highlands from at least 1.6 to 1.4 million years ago.

The researchers suggest that the lack of fossil record for this species is likely due to their preference for highland habitats and the scarcity of paleontological sites in these areas, particularly outside the East African Rift System. They further suggest that the genetic data from their research and the discovery of the MW5-B208 specimen support the idea that the Ethiopian wolf has survived previous population crashes over the course of this time frame.

“Our research indicates that the Ethiopian wolf faced multiple extinction threats during periods of globally warm climates,” explained Professor Erella Hovers, one of the leading researchers of the study, in a statement sent to IFLScience. “The recovery of the species occurred when colder conditions allowed the expansion of populations into lower areas, increasing the species’ territories and promoting connectivity between populations. The Melka Wakena fossil, recovered from a site at an altitude of 2,300 meters above sea level, likely represents such a recovery period.”

The team stresses the importance of finding conservation solutions that can work towards protecting this iconic African species.

The paper is published in Communications Biology.

Source Link: First-Ever Ethiopian Wolf Fossil Found Sheds Light On Their African Arrival