For the first time, astronomers have detected a burst of light from the smaller of two supermassive black holes (SMBH) within the blazar OJ 287. The smaller SMBH’s orbit regularly causes it to trigger outbursts in the larger SMBH’s accretion disk and the pair’s dance has drawn astronomers’ attention for decades, but this is the first light thought to be from the smaller black hole’s direct emissions

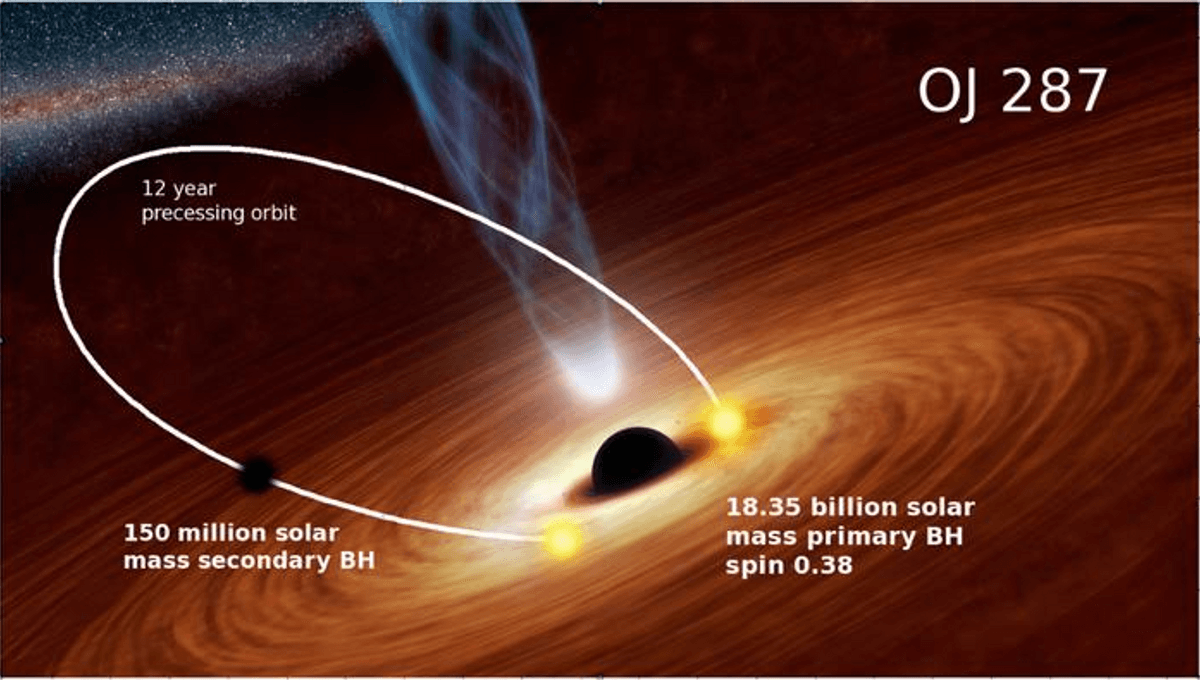

OJ 287 has interested astronomers since 1888, long before we even knew galaxies are not part of our own Milky Way. The smaller black hole orbits the larger one every 12 years, and the angle of its orbit causes it to pass through the accretion disk twice in that period, releasing bursts of light that last about a fortnight.

A briefer bright flash outside the galaxy’s regular cycle revealed something unusual going on. In a new paper, astronomers from Finland and India come together to explain the observations.

Most, if not all, galaxies have SMBHs at their core. When galaxies merge, the black holes usually end up combining – but before that happens, they orbit each other in an ever-tightening dance. Although we can’t see the black holes themselves, in about a dozen cases we are able to watch the radiation produced by these interactions as the black holes close in.

OJ287 is one of these, and at five billion years away is a relatively close example. The SMBHs are also unusually close to each other. At an estimated 18 billion solar masses, the large SMBH is 4,000 times more massive than the one at the heart of our own galaxy, and around a fifth of the largest SMBH known. All this makes the system one of the few cases where there are good prospects for detecting gravitational waves from their mutual orbits, but also prevents us from resolving the two objects’ disks independently.

Forty years ago, Aimo Sillanpää of Finland’s University of Turku made sense of the pattern of flashes by identifying two cycles for his PhD. One, which lasts 12 years, represents the time it takes the smaller SMBH to orbit the larger one, with two outbursts a cycle as it passes through the primary’s accretion disk, heating it in the process enough to dramatically brighten.

The longer cycle involves changes to the way the orbit is orientated relative to the disk, like the way Earth’s orbit slowly evolves in a much longer cycle of stretching and shrinking. On this basis, Sillanpää successfully predicted one of OJ 287’s biggest flares in 1983. The calculations are complicated because the gravity of the smaller hole has bent the larger one’s accretion disk out of shape. Nevertheless, refinement of the model has led to getting predictions accurate to within a few hours.

However, when a flash was detected from OJ287 in early 2022, it didn’t fit the pattern Sillanpää had identified, since the regular bursts had occurred in 2015 and 2019. In a paper by Sillanpää and 26 co-authors, the out-of-sequence outburst is attributed to the smaller SMBH, which captured new gas on its passage through the larger hole’s disk, eventually swallowing it. “It is the swallowing process that leads to the sudden brightening of OJ287,” lead author Professor Mauri Valtonen of the University of Turku said in a statement. “It is thought that this process has empowered the jet which shoots out from the smaller black hole of OJ 287. An event like this was predicted ten years ago, but has not been confirmed until now,”

Valtonen argues out-of-cycle outbursts like this have occurred before, but they have not previously been detected because they are so short, only lasting a day. While astronomers have been monitoring OJ 287 since 1970, after occasional observations since the 19th century, we’re not checking at all times so short bursts can be missed. Indeed, even the longer brightening in 2019 was invisible from Earth because the Sun was in the way, and only seen because of the Spitzer telescope’s trailing orbit.

The study is published open access in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

Source Link: First Observations Of Secondary Supermassive Black Hole Within Famous Double-Hole Quasar