Two species of giant hummingbirds inhabit the Andes, rather than just one as previously assumed, a new study has revealed. The birds are distinguished by only tiny differences in their bodies – but their lifestyles could hardly be less alike, with one undertaking epic migrations while the other stays at high altitudes year-round.

Humanity’s poor understanding of South American wildlife was revealed recently with the announcement of a new species of giant anaconda, the largest and heaviest snake in the world. That discovery revealed substantial genetic differences between green anacondas from different parts of the Amazon, such that they deserve classification as two separate species.

It’s easier to understand how a bird weighing 17-31 grams (0.6-1.1 ounces) could fly under our radar for so long than a 6-meter snake. Nevertheless, the scientific description of the largest hummingbird species is another example of how badly under-resourced the continent’s taxonomy is.

“These are amazing birds,” lead study author Cornell University’s Dr Jessie Williamson said in a statement. “They’re about eight times the size of a Ruby-throated Hummingbird. We knew that some Giant Hummingbirds migrated, but until we sequenced genomes from the two populations, we had never realized just how different they are.” The observation that some hummingbirds leave the coast after their breeding season goes back at least as far as Darwin, who speculated they might travel to the Atacama Desert.

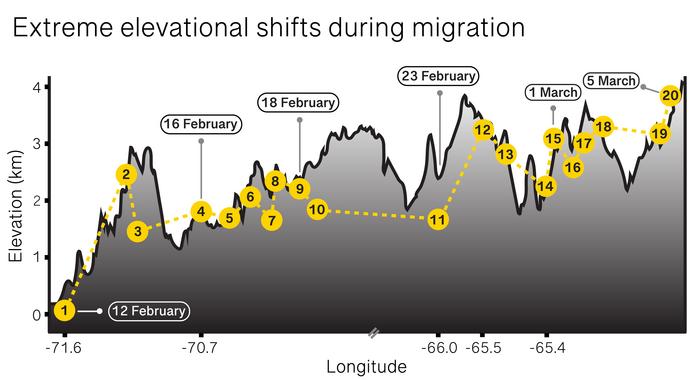

The researchers discovered that northern giant hummingbirds live in the high Andes throughout the year, but a southern population breeds at the coast, spending their winters high in the mountains. Their journey is short compared to species that fly from the Arctic to the Antarctic and back each year, but it’s extraordinary in terms of altitude, from sea level to 4,100 meters (14,000 feet) up.

“They are as different from each other as chimpanzees are from bonobos,” said Dr Chris Witt of the University of New Mexico. “The two species do overlap on their high elevation wintering grounds. It’s mind-boggling that until now nobody figured out the Giant Hummingbird mystery, yet these two species have been separate for millions of years.”

Even with local assistance, the team did not anticipate finding a new species, so their work was not designed to test the relationship. Instead, they were seeking to find out where the migratory birds went in winter. After using satellite trackers to follow eight birds’ movements thousands of kilometers north to Peru, the team realized something special was going on. The 8,300-kilometer (5,200-mile) round-trip is quite likely the longest hummingbird migration in the world.

It’s a long way to the top if you’re a small bird, and when the top has so little oxygen you need to stop to pump up your blood.

Image Credit: Jessie Williamson

Understandably, birds that have seen the ocean, and tasted the exotic nectar to be found there, have little interest in breeding with those that never leave home. Nevertheless, sometimes love (or lust) will find a way – one hybrid has been found. The authors are not sure whether all giant hummingbirds once migrated and some got too lazy, or if it’s the great journey that is the innovation that caused the species split.

The species name, Patagona gigas, was once thought to describe both, but was described using a migratory bird, so these get to keep the name. The team are calling the homebodies Patagona chaski, from the Quechua word for messenger.

The common names are simpler, with the migrators to be known as Southern Giant Hummingbirds, and their stay-at-home counterparts Northern Giant Hummingbirds.

The fact this study took 15 years helps explain why no one had recognized the difference before. “Capturing Giant Hummingbirds is very challenging,” study author Emil Bautista of the Centro de Ornitología y Biodiversidad, Peru, said. “They watch everything and they know their territories well. We had to be strategic in choosing sites for our nets. If Giant Hummingbirds see something unusual, they won’t visit that spot. They are more observant than other birds.” It took an average of 146 hours with nets to catch a single bird.

Once caught, the birds needed to be tracked. So “miniature backpacks” light enough not to affect the hummingbird’s capacity to fly were attached to the birds. More innovatively, Williamson found a way to make it wearable without interfering with the hummingbirds’ distinctive hovering flight while drinking nectar.

“It took a lot of trial and error to come up with a suitable harness design,” Williamson said in another statement. “Hummingbirds are challenging to work with because they are lightweight with long wings and short legs. They’re nature’s tiny acrobats.”

A Southern Giant Hummingbird being fitted with a geolocator backpack in Valparaíso Region, Chile

Image Credit: Chris Witt

Neither species is currently endangered, despite migratory birds often being particularly vulnerable. The team is keen to explore the region where the two’s habitats overlap to see how they interact. Williamson also wants to understand how they change altitude so rapidly. “They’re like miniature mountain climbers. How do they change their physiology to facilitate these movements?” she said. One of the team’s discoveries was that the birds pause on their upward migration to acclimatize, with their hemoglobin levels surging.

The findings are published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Source Link: First Snakes, Now Hummingbirds, World’s Largest Species Revealed To Be Two