Once upon a time, humans were just one of quite a few hominid species roaming the planet, just trying to eke out a survival with nothing but an overgrown frontal lobe and a stubborn attitude to their name.

Today, we’re alone – and those evolutionary cousins are a mystery. But here’s the thing: we know more about them than you might think. And it turns out that most of what you were taught by TV shows and popular culture is complete nonsense.

Here are five facts about Neanderthals that you may find surprising.

You’re probably part Neanderthal – and that’s a good thing

We like to think of Neanderthals as being a distant, ancient relative – but really, they were still kicking about some 40,000 years ago. In evolutionary terms, that’s not all that long ago, and it’s certainly well after Homo sapiens – that is, us – hit the scene.

“We know Neanderthals and humans quite definitively had a large overlap,” Elena Zavala, a paleo and forensic geneticist at the University of California, Berkeley, told NBC News this year.

Estimates range from a couple of millennia to as much as ten thousand years, but the idea that humans and Neanderthals met, and mixed, is undeniable. And by “mixed”, we mean… bow chicka wow wow.

“It seems that 99.7 percent of Neanderthal and modern human DNA is identical,” wrote Mark Maslin, Professor of Earth System Science at UCL; Trine Kellberg Nielsen, Associate Professor, Department of Archeology and Heritage Studies at Aarhus University; and Peter C. Kjærgaard, Professor of Evolutionary History and Director of the Natural History Museum of Denmark, University of Copenhagen, in a 2022 article for The Conversation.

“Many Europeans and Asians have between 1 percent and 4 percent Neanderthal DNA while African people south of the Sahara have almost zero,” they explained. “Ironically, with a current world population of about 8 billion people, this means that there has never been more Neanderthal DNA on Earth.”

But if you’re worried about what sort of things you might have inherited from great-grandpa Ug, don’t fret. Not only were Neanderthals not the boneheads you’re probably imagining – we’ll get to that later – but actually, it might be doing you a favor.

“There are [DNA] sequences inherited from Neanderthals […] which likely helped humans fend off exposure to new pathogens,” wrote Joshua Akey, a Professor at the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics at Princeton University, in The Conversation in 2022.

“Neanderthal sequences have been shown to influence both susceptibility to and protection against severe COVID-19,” he added. “Archaic hominin sequences have also been shown to influence susceptibility to depression, Type 2 diabetes and celiac disease among others.”

Neanderthals didn’t look how you think (and the reason why is pretty ridiculous)

Hear the name “Neanderthal”, and it’s likely a very specific picture that comes to mind. Short, stocky, slow; probably saying something like “oog ug” before bashing their bestie in the face with a rock; that kind of thing.

That’s entirely wrong. Well, ok – it’s not totally wrong. Neanderthals were shorter and stockier than us – but they were far from slow, either mentally or physically.

“Neanderthals were skilled tool makers […] proficient hunters, intelligent and able to communicate,” explains the Natural History Museum. “Healed and unhealed bone damage found on Neanderthals themselves suggest they killed large animals at close range – a risky strategy that would have required considerable skill, strength and bravery.”

So why, then, do we associate the species with this image of the shambling brute? It’s actually all thanks to one guy: the French paleontologist and geologist Pierre-Marcellin Boule. It was he who, in 1911, reconstructed the first relatively complete Neanderthal skeleton known to science – now known as the Old Man of La Chapelle – and, guided by the bones and his own preconceptions, he built it with bent knees, forward flexed hips, with the skull jutting forward over a slouched, stooping stance.

But was he on the money? Turns out, no. What Boule thought was evidence of a primitive, ape-like physiology was actually evidence of osteoarthritis and advanced age. “While that vision of the Old Man was hugely influential in creating persistent negative perceptions of Neanderthals, it doesn’t match modern understanding of their biology,” wrote paleolithic archaeologist Rebecca Wragg Sykes in a 2021 BBC Future article.

“In peak condition they were strong, highly athletic and certainly nothing like a missing link to gorillas or chimpanzees,” she explained. “They were fully upright, and while slightly shorter and with a slight difference in gait, biomechanical modeling suggests they walked just as efficiently as living people.”

Neanderthals had a sense of bling

So, you live in a cave – yes, some Neanderthals really did live in caves – and spend your life trying not to die from exposure to a sabretooth tiger. You wouldn’t think you’d have time to concentrate on aesthetics – and yet, research has shown that Neanderthals actually did seem to have a sense of style.

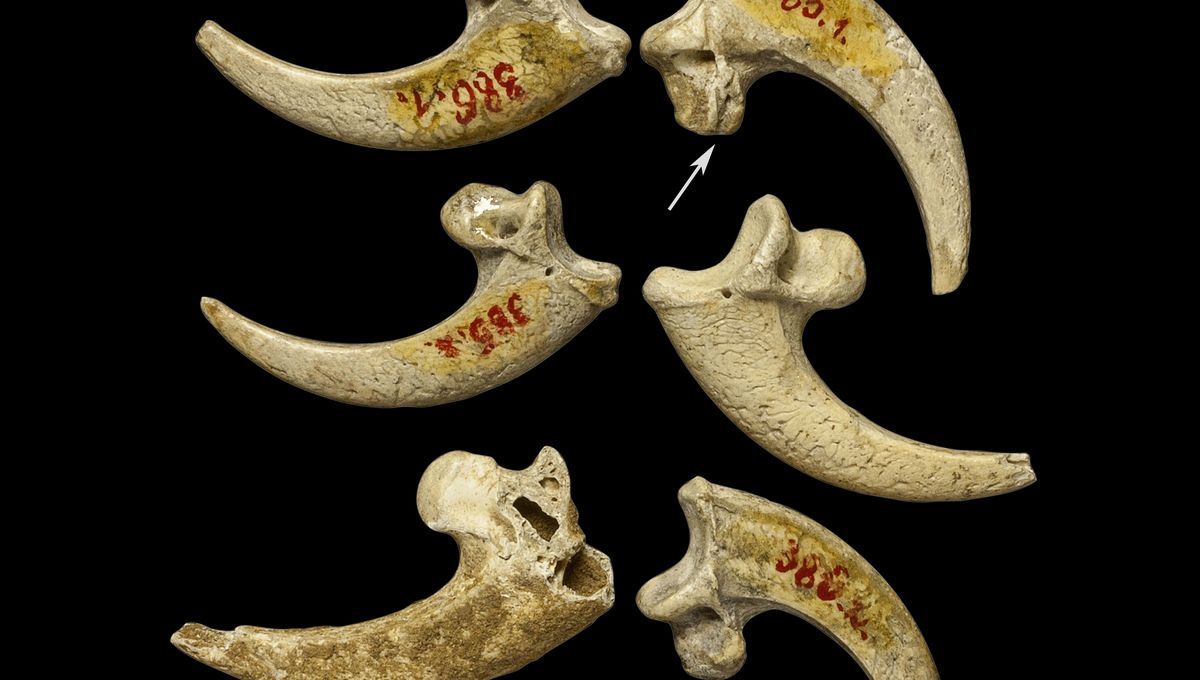

Not only is that evident from the multiple pieces of jewelry found alongside Neanderthal fossils – delicate necklaces made with tiny beads of animal teeth, shells, and ivory; or punk-rock-looking bracelets made from eagle talons – but it’s also shown in the remnants of pigment that hint at, well, Neanderthal makeup.

And boy, were these ancient hominids fabulous. It’s “glitter makeup,” University of Bristol archaeologist Joao Zilhao told NPR in 2010. “Or shimmer makeup […] where you, over a foundation, you add shiny bits of something granular that shines and reflects. When light would shine on you, you’d reflect.”

Now, that’s interesting – but it’s also important. As far as anthropologists are concerned, you don’t paint your face and wear glitzy jewelry unless you’re capable of something called “symbolic thinking” – that is, using signs and symbols as abstract representations of ideas.

Alison Brooks, an anthropologist at George Washington University, said that “Neanderthals went up a notch in my thinking,” when she saw the ancient bling. “This is certainly the oldest and strongest evidence for Neanderthal symbolic behavior beyond just pigment use.”

Neanderthals were caring and compassionate

Life for Neanderthals was painful, basically from start to finish. “When you look at adult Neanderthal fossils, particularly the bones of the arms and skull, you see [evidence of] fractures,” Erik Trinkaus, an anthropologist at Washington University in St. Louis, told Smithsonian Magazine back in 2003. “I’ve yet to see an adult Neanderthal skeleton that doesn’t have at least one fracture, and in adults in their 30s, it’s common to see multiple healed fractures.”

And yet, despite this constant risk of injury and disease, we know that they were able to survive into old age – or at least, what passed for old age back in 60,000 BCE. The Old Man, for example, isn’t named that ironically: “He was quite old by the time he died, as bone had re-grown along the gums where he had lost several teeth, perhaps decades before,” the Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Initiative points out. “In fact, he lacked so many teeth that it’s possible he needed his food ground down before he was able to eat it.”

But people don’t just recover from broken bones and survive into old age despite debilitating degenerative illnesses by accident. The only conclusion is that Neanderthals were not just social, but actively cared for each other through disease and injuries.

“Neanderthals didn’t think in terms of whether others might repay their efforts, they just responded to their feelings about seeing their loved ones suffering,” explained Penny Spikins, senior lecturer in the Archaeology of Human Origin at the University of York and lead author of a 2018 study into Neanderthal society, in a statement.

“Interpretations of a limited or calculated response to healthcare have been influenced by preconceptions of Neanderthals as being ‘different’ and even brutish,” she said. “However, a detailed consideration of the evidence in its social and cultural context reveals a different picture […] organized, knowledgeable and caring healthcare is not unique to our species but rather has a long evolutionary history.”

People have seriously suggested bringing Neanderthals back from extinction… and that’s totally possible, by the way

Scientists are all talking about de-extincting the dodo or the wooly mammoth – so why can’t we do the same with our once-fellow human species?

Well, according to George Church, Professor of Genetics at Harvard Medical School, Professor of Health Sciences and Technology at Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology – plus a whole host of other impressive positions – we totally could. In fact, it would likely be possible sooner than we think.

“The reason I would consider it a possibility is that a bunch of technologies are developing faster than ever before,” Church told Der Spiegel in 2013. “In particular, reading and writing DNA is now about a million times faster than seven or eight years ago. Another technology that the de-extinction of a Neanderthal would require is human cloning. We can clone all kinds of mammals, so it’s very likely that we could clone a human. Why shouldn’t we be able to do so?”

Why indeed? The first step, Church said, would be to sequence the Neanderthal genome – something which we actually achieved nearly a decade and a half ago, when paleogeneticist Svante Pääbo did what was at the time thought to be impossible and successfully sequenced the species’ DNA from three skeletons found in Croatia (he would later be awarded a Nobel Prize for this breakthrough).

From there, it would be a matter of synthesizing the genome and introducing it to a human stem cell. “If we do that often enough, then we would generate a stem cell line that would get closer and closer to the corresponding sequence of the Neanderthal,” he explained.

“We developed the semi-automated procedure required to do that in my lab,” he assured Der Spiegel. “Finally, we assemble all the chunks in a human stem cell, which would enable you to finally create a Neanderthal clone.”

So, theoretically possible – but in practice, there are a few stumbling blocks. The biggest one? The need for what Church labels an “extremely adventurous female human” to act as surrogate for the Neanderthal baby. Then there are the ethical and legal implications – human cloning is currently banned by the UN, and that’s unlikely to change just because some scientists want to see what would happen if we brought Neanderthals back from the dead.

But if we could – well, who knows what we might learn. “Neanderthals might think differently than we do,” Church said. “We know that they had a larger cranial size. They could even be more intelligent than us.”

“When the time comes to deal with an epidemic or getting off the planet or whatever, it’s conceivable that their way of thinking could be beneficial,” he suggested.

All “explainer” articles are confirmed by fact checkers to be correct at time of publishing. Text, images, and links may be edited, removed, or added to at a later date to keep information current.

Source Link: Five Fascinating Facts About Neanderthals That Could Change How You See Them