Fashions rise and fall, styles change, but when it comes to looking good, one law has held depressingly strong throughout history: pain is beauty.

Whether it was 18th-century French noblewomen wearing dresses so heavy and restrictive that they needed a boot camp just to walk in the things, Naomi Campbell turning her ankle in a pair of nine-inch heels in 1993, or just a too-tight pair of skinny jeans, it seems we as a species have always been just a little too ready to go the extra incredibly risky step to look good.

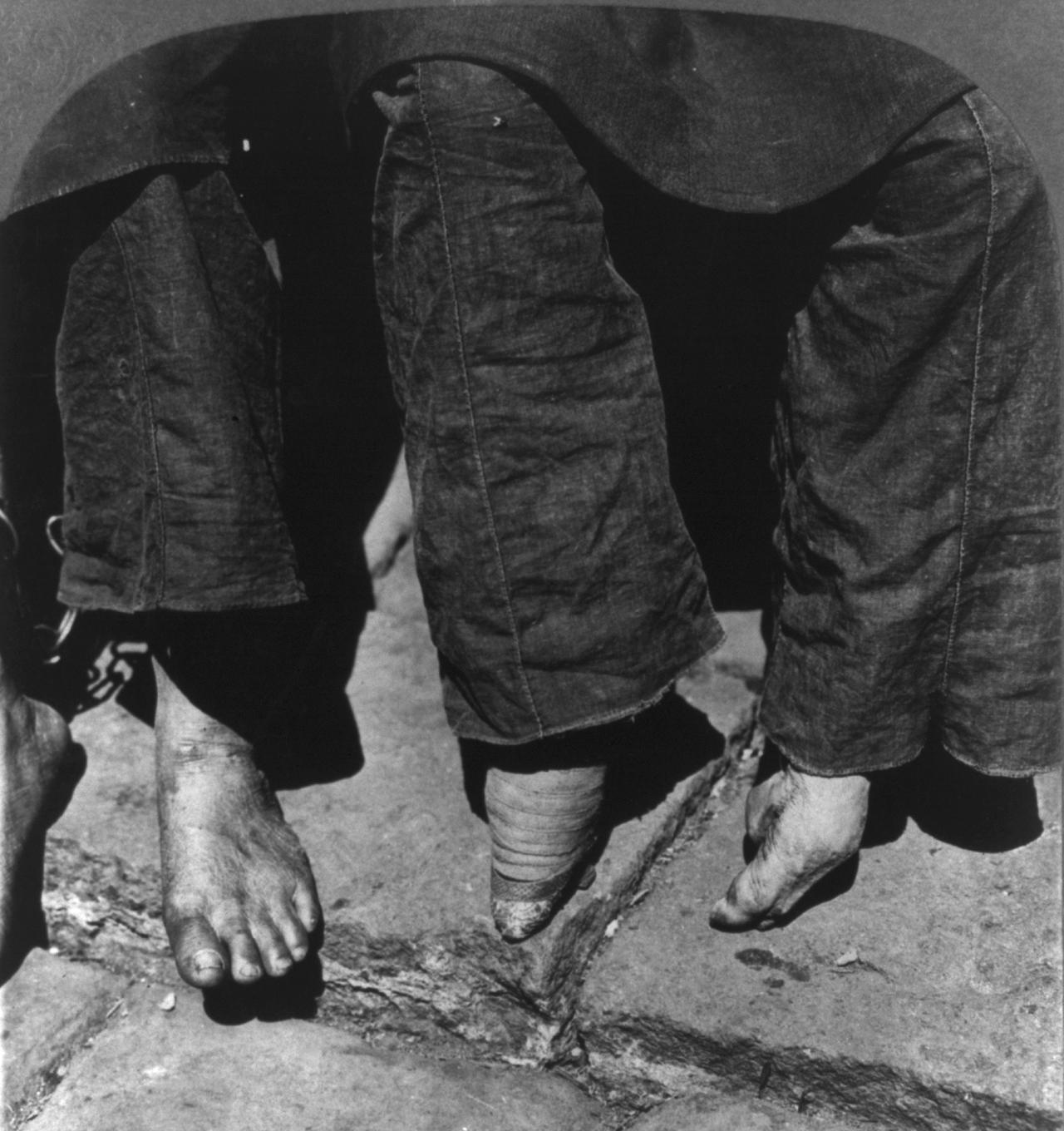

However, there’s not much that comes close to one particular trend: foot binding.

An extreme practice that held sway across China for the best part of a thousand years, it caused deformities and disabilities in up to half the female population of the country at times – all for the sake of looking pretty.

But what was foot binding? How did it work? And why on earth did it catch on so hard? Let’s find out – but beware: the following makes for some pretty grim reading.

What is foot binding?

Picture the scene: you’re a little girl – maybe five years old, maybe younger – in Imperial China. One day, your grandmother, or perhaps an aunt or other elder woman in your family, takes you aside and sets about making sure you can find a good husband as an adult. She does it, as it was done to her, by breaking every one of your toes except the biggest, forcing them under the arch of your foot, also forcibly broken, wrapping it tightly so that the bones can’t right themselves again.

You are then forced to walk on this painful mess, “in order to help re-establish circulation,” contemporary guides would advise. Sometimes, pieces of the foot would be cut away or encouraged to rot off, so as to better approximate the ideal triangular footprint.

Later, when it’s all healed up in this new, mangled state, it would happen all over again.

X-ray of bound feet. Image Credit: Everett Collection/Shutterstock.com

After her mother died, “I bound my own feet,” said Wang Lifen, one of the last remaining women with bound feet alive in China, in a 2007 interview with NPR. “I could manipulate them more gently until the bones were broken.”

“Young bones are soft, and break more easily,” she explained.

The smaller the foot, the reasoning went, the more attractive the girl – and the ultimate goal was the so-called “lotus foot”. To appreciate what a drastic diversion from nature that was, just look at your own foot, and then look at your smartphone: “Placed side by side, the [lotus] shoes were the length of my iPhone and less than a half-inch wider,” wrote Amanda Foreman in a 2015 piece for Smithsonian Magazine.

“My index finger was bigger than the ‘toe’ of the shoe,” she recalled. “It was obvious why the process had to begin in childhood when a girl was 5 or 6.”

When did foot binding begin?

As is the case with many things with origins stretching back over a millennium, sources are scarce on the exact beginnings of foot binding. The generally accepted story, though, is that it started sometime in the second half of the 10th century, during the reign of Emperor Li Yu of the Southern Tang dynasty.

The practice “is said to have been inspired by a tenth-century court dancer named Yao Niang who bound her feet into the shape of a new moon,” explained Foreman. “She entranced Emperor Li Yu by dancing on her toes inside a six-foot golden lotus festooned with ribbons and precious stones.”

From there, foot binding took off in a big way. There are multiple references to the practice in the 11th and 12th centuries, and by the mid-13th century it had become so widespread that we have physical evidence for foot binding in the archeological record.

Despite the horrific nature of the practice to modern eyes, back in Imperial China bound feet were seen as the ultimate erogenous zone, with pornographic books from the Qing dynasty listing nearly 50 different ways of playing with the tiny tootsies.

Photograph of a woman with bound feet in 1911. Image Credit: Public Domain, Underwood & Underwood, London & New York,

Before too long, it was simply the norm for women across the country – so much so that it was unbound feet that started to be seen as “unnatural”. Without small feet, it would be pretty much impossible to live a successful life or make your clan proud: in short, wrote Susie Lan Cassel, a literature professor focusing on Chinese cultural lore, back in 2007, “in all classes of society women’s feet became markers of their prestige, talent, and gender… women’s economic security depended upon marriage, and a good marriage was determined, in part, by the quality of the bound feet.”

What are the problems with foot binding?

As you might imagine from a practice that required the repeated breaking of bones and deformation of the body’s main connection point with the Earth, foot binding was not without problems for those who underwent it.

So, remember how bound feet were seen as an erogenous zone, specifically referenced in the regional and temporal equivalent of porno mags? Each to their own, of course, but what you might not have gathered so far is that those supposedly sexy feet smelled really, really bad.

“The bandages that women used for footbinding were about 10 feet long, so it was difficult for them to wash their feet,” author Yang Yang told NPR. “They only washed once every two weeks, so it was very, very stinky.”

Some of that stink may well have come from the frequent infections, occasionally leading to gangrene, caused by the process of foot binding. Toenails would sometimes grow straight into the foot, again causing pain and infections – one common way of fending this off would be to simply peel the toenails off of the feet entirely.

Now, that may be gross, but it’s far from the worst problem girls and women could expect from having their feet bound like this. By some estimates, the pain of having all the bones in your foot broken like this was so bad that as many as one in ten girls died from shock within the first few days of undergoing the procedure.

Then, if they survived that, they had a lifetime of health problems and disabilities to look forward to. In the early 1990s, an American epidemiologist named Steve Cummings went to Beijing to study the apparent hardiness of Chinese elderly women over their American counterparts – hip fractures, it seemed, were remarkably less frequent in China than the US.

What the study ended up revealing turned that idea on its head. It was just the second participant who “came in with two canes and her foot wrapped up oddly,” Cummings told The Atlantic in 2020.

At first, he “thought it was just curious,” he explained – after all, he had been all over the country by this point, and had never seen a woman with this type of feet. But as the study progressed, more and more women started coming in with these tiny, deformed feet.

In the end, around 15 percent of the women involved in the study were found to have had their feet bound as children – and those women, Cummings reported, were much more likely to have significant health problems and restrictions. They were more likely to have fallen in the previous year than other women in the cohort, had lower bone density in their hips and lower spines, and had greater trouble getting up from a chair without assistance.

So why hadn’t he seen these women in his travels around the country beforehand? Simply, their feet did not allow them to be out enough to get seen. It was only now, with transport to and from the hospital provided to take part in a randomized study, that they were able to venture any appreciable distance from their homes.

“The way these women avoided injury,” Cummings told The Atlantic, “was by not doing anything.”

When did foot binding end?

For something that lasted so long, you might think foot binding had some kind of official support from on high. In reality, though, there were many attempts to outlaw the practice throughout the centuries – it’s just that they weren’t very successful.

There had always been some level of resistance to foot binding – even back in the 13th century, when the practice had barely become mainstream, the scholar Che Ruoshui wrote that “little girls not yet four or five years old, who have done nothing wrong, nevertheless are made to suffer unlimited pain to bind [their feet] small. I do not know what use this is.”

It wasn’t until the end of the 19th century, with the influx of Western missionaries and Chinese intellectualism, that reform movements started seeing more influence.

In 1902, Empress Dowager Cixi issued an edict against the practice, and ten years later, after the Xinhai Revolution ended Imperial rule in the country and installed the Republic of China, the new government banned it once again. Neither of these commands proved particularly successful, however: “When people came to inspect our feet, my mother bandaged my feet, then put big shoes on them,” Zhou Guizhen told NPR. “When the inspectors came, we fooled them into thinking I had big feet.”

Why did people cling so hard to this damaging tradition? Recent research suggests a motive that went further than just securing a good marriage – after all, Western women have been subject to some pretty dangerous and deforming trends throughout history in the name of finding a husband, but none lasted a thousand years. The difference with foot binding, though, was that it came with one massive benefit – at least if you weren’t the one undergoing the procedure. It kept your girls from running around when they could be sitting still and working.

“In the conventional view, [foot binding] existed to please men. They were thought to be attracted to small feet,” Laurel Bossen, co-author of the book Bound feet, Young hands, told CNN in 2017.

However, “the image of them as idle sexual trophies is a grave distortion of history,” she continued. In truth, she explained, the reason foot binding remained so popular for so long was that it provided a tangible economic benefit, particularly for rural families. With bound feet limiting their movement so significantly, foot binding ensured young girls would stay at home, making the vital goods like yarn, cloth, mats, shoes, and fishing nets that their families depended upon for income.

To support that idea, Bossen pointed to the demographics where the practice held on longest: it endured in areas where goods like cloth were still being made at home, and began to decline only when cheaper factory-made alternatives became available in these regions. The first people to repudiate the practice, meanwhile, were often students and educated women – urbanites who wanted to be seen as “modern” and “civilized”.

It was in 1949, when the Communist government came into power, that foot binding really dropped out of fashion and into the history books. Women whose tiny feet had previously won them a wealthy husband were now performing hard physical labor to make China’s Great Leap Forward possible, on feet barely bigger than a five-year-old’s.

“These women were shunned by two eras,” Yang told NPR. “When they were young, footbinding was already forbidden, so they bound their feet in secret. When the Communist era came, production methods changed. They had to do farming work, and again they were shunned.”

Even against all this resistance, the last known case of foot binding was recorded in 1957 – still within living memory for a vast swathe of the population. Today, however, the practice is more of an embarrassing blot on the history books – a regretful, thousand-year fashion mistake – than a secret fashion that refuses to die.

And after all these years, Zhou told NPR, “I regret binding my feet.”

“I can’t dance, I can’t move properly. I regret it a lot,” she said. “But at the time, if you didn’t bind your feet, no one would marry you.”

Source Link: Foot Binding: The Extreme Fashion That Caused 1,000 Years Of Broken Bones