In the heart of the Sahara, an area that is now in southwestern Libya, a great empire built a city and towns. These represent the oldest known example of a large permanent human population living without access to a river or lake. Their success, now being explained, is a testimony to human ingenuity – and a warning about our tendency to waste the gifts the Earth gives us.

For 5,000 years, the Sahara has been one of the hardest places on the planet for humans to live. Before that, however, it was a savanna similar to the modern Serengeti with waterholes and plenty of animals to hunt. We know humans thrived in the earlier conditions, indeed it’s thought to be one of the two places where pottery was invented.

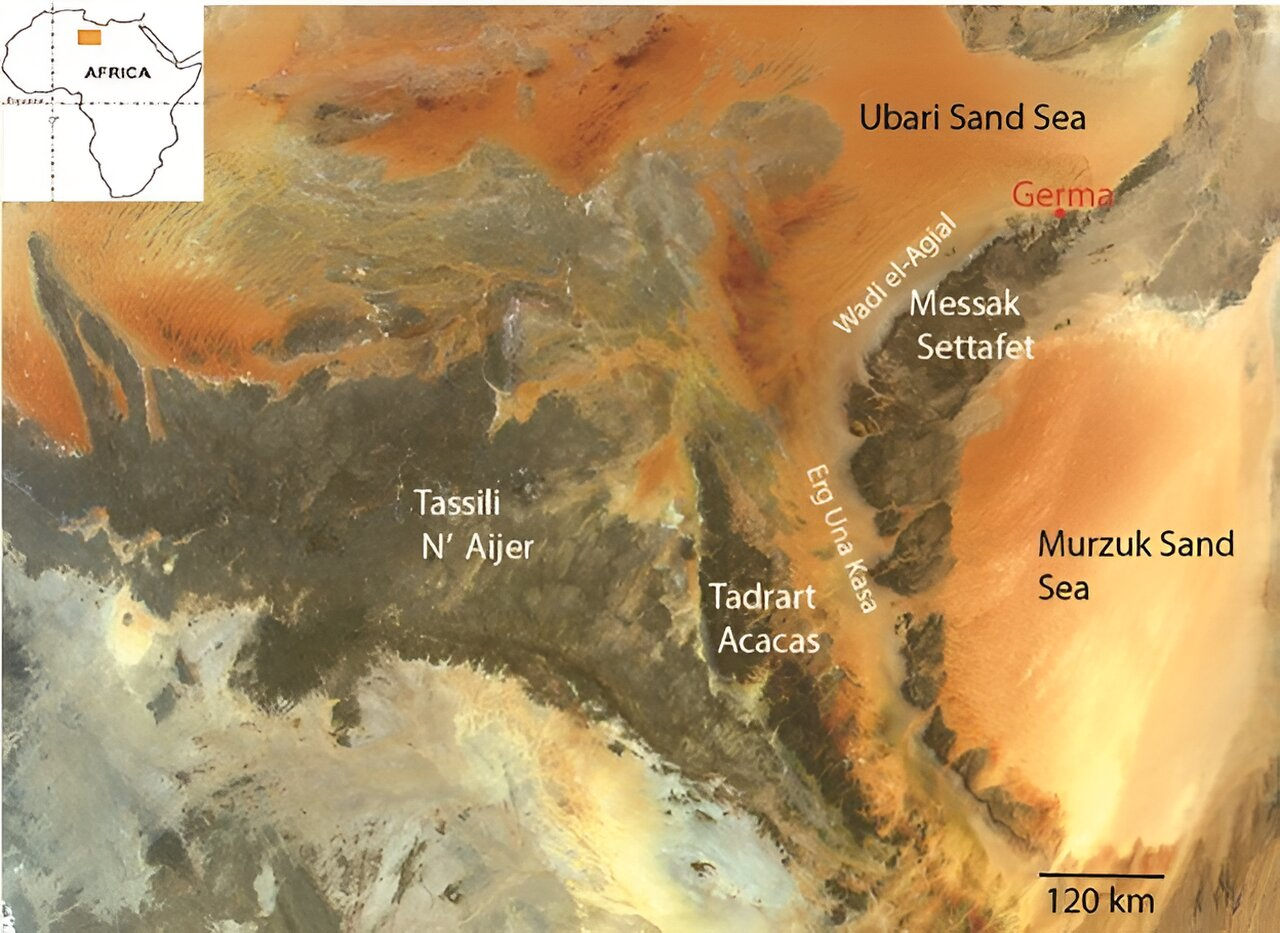

By the time the Garamantes were building their society 2,400 years ago, however, the Sahara was much like it is today – a baking desert challenging to cross, let alone live in. However, those previous conditions had left an underground legacy at certain locations, including the Garamantes’ home at Wadi el-Agial.

The Garamantes’ genius was to find the one place in the Sahara where the groundwater sat high enough above the valley floor to be tapped

Image Credit: NASA/Luca Pietranera

Much of this groundwater was buried too deep to be accessible in the quantities needed to sustain agriculture without modern technologies. However, at Wadi el-Agial, some of it sat higher in the landscape. According to Professor Frank Schwartz of Ohio State University, the Garamantes dug angled tunnels (known as qanats or foggara in the Berber language) into water-rich hillsides, and used the water that flowed out to irrigate valleys below.

This technique was used by other ancient civilizations in dry areas, although not as dry as the one the Garamantes faced. Schwartz believes they got the idea from Persia, who had pioneered it more than a millennium before.

The Garamantes were referenced by writers of the era, but much of the reporting was incorrect, with some even attributing their feats to the Romans. Since the 1960s, archaeology has corrected many of the misunderstandings, but the question of why there was so much groundwater for them to tap was unresolved.

Schwartz says the sandstone aquifer under this part of the Sahara is one of the largest in the world when full. Although the Sahara has been a fertile grassland several times relatively recently, it is millions of years since it has been genuinely wet. However, Schwartz has shown that the geology of the area meant that during a period when the Sahara still had rainy seasons, water from a large catchment area flowed to the base of the Messak Settafet massif. There it provided water to the Garamantes for centuries.

Water flows downhill, even when it is underground, but if the floor of a valley sits below the top of the groundwater in the hills it can be available without pumping

Image Courtesy: Frank Schwartz

Wadi el-Agial probably seemed like paradise to the Garamantians. They captured slaves to do the hard digging to get their water and were immune to droughts; floods would seldom have been a problem. With vast deserts between them and any civilization of similar size, they were probably almost unique at the time in facing little threat of invasion. Historians believe their standard of living was higher than anyone else in the Sahara region during ancient times.

However, with humanity’s usual attitude to scarce resources, the Garamantes dug 750 kilometers (450 miles) of tunnels into the aquifer to access its contents, with the longest reaching 4.5 kilometers (2.7 miles). With recharge having almost stopped once the region turned dry the outcome was inevitable.

“The qanats shouldn’t have actually worked,” Schwarts said in a statement. “Because the ones in Persia have annual water recharge from snowmelt, and there was zero recharge here.” Eventually, the ancient bounty ran out, with the groundwater dropping below the level of the tunnels. For a while, more carefully placed digging may have kept the problem at bay – but around 1,600 years ago, the civilization was abandoned.

Schwartz doesn’t hide the implications for us. “As you look at modern examples like the San Joaquin Valley, people are using the groundwater up at a faster rate than it’s being replenished,” he notes. “California had a great wet winter this year, but that followed 20 years of drought. If the propensity for drier years continues, California will ultimately run into the same problem as the Garamantians. It can be expensive and ultimately impractical to replace depleted groundwater supplies.”

The situation is not identical of course, since we extract the water using pumps rather than gravity, but that merely buys us more time.

The study was presented at the Geological Society of America’s 2023 conference.

Source Link: For 800 Years A Sahara Civilization Flourished, Then The Groundwater Ran Out