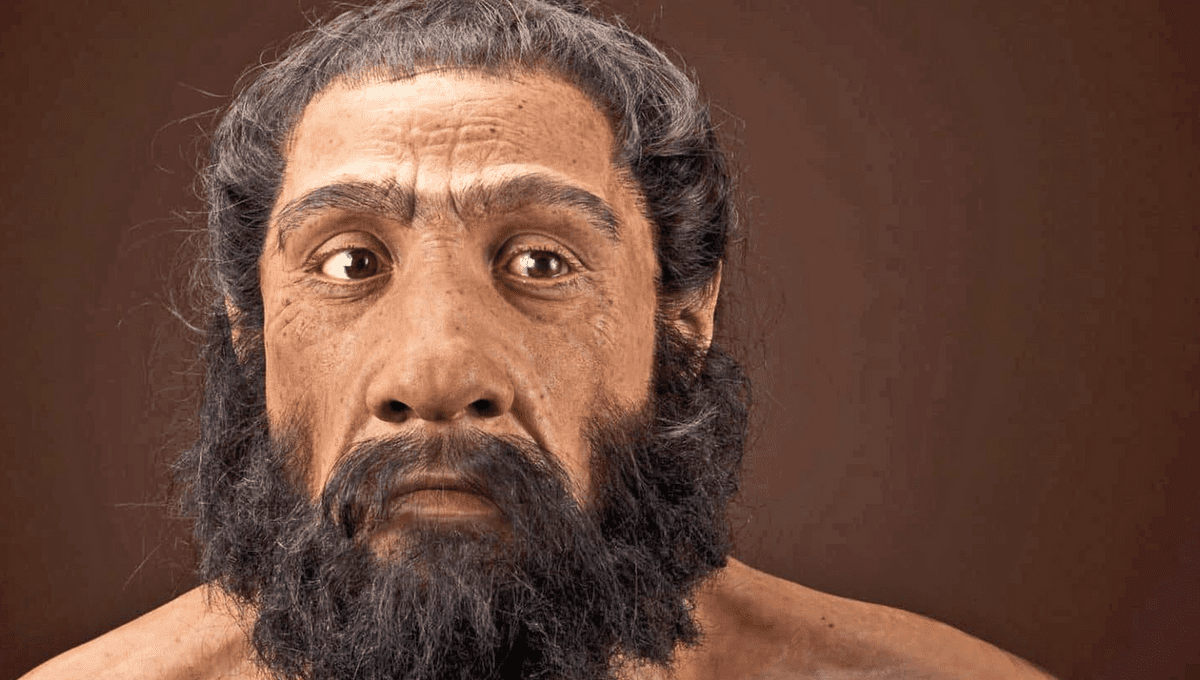

The sequencing of Neanderthal DNA has revealed modern humanity’s partial descent from what was once thought to be a separate branch of the human family tree. Yet working out where and when these encounters happened has proven harder. Indeed, it’s hard to make sense of the evidence we have. By looking at the facial features of ancient skulls, some scientists have added credibility to the idea that most mating took place in a small space and possibly time.

Neanderthals and Homo sapiens appear to have overlapped in Europe longer than anywhere else, so anthropologists expected that would be where the greatest modern concentrations of their genes would lie. Instead, people with mostly Asian ancestry tend to have more Neanderthal in their genetic code.

The easiest way to explain modern patterns is if the two populations mated mostly in the area between the Mediterranean and the Tigris/Euphrates rivers at least 65,000 years ago. Yet that hypothesis still looks shaky since we don’t understand why. A paper in Biology has given it some support by comparing the features of skulls from different periods and locations to see which show the strongest Neanderthal resemblance.

“We often think of evolution as branches on a tree, and researchers have spent a lot of time trying to trace back the path that led to us, Homo sapiens,” said Professor Steven Churchill of Duke University in a statement. “But we’re now beginning to understand that it isn’t a tree – it’s more like a series of streams that converge and diverge at multiple points.”

Neanderthals broke away from the main Homo Sapiens channel 315,000-800,000 years ago, but at some points, the two tributaries converged enough for genes to cross.

If we could extract DNA from every fossil specimen, we’d probably have a very clear picture of these convergences. However, most ancient genomes are far too degraded for this, particularly if located in hot climates. Skull shapes are much more robust.

“By evaluating facial morphology, we can trace how populations moved and interacted over time,” said co-author Professor Ann Ross of North Carolina State University. “And the evidence shows us that the Near East was an important crossroads, both geographically and in the context of human evolution.”

The authors used published data on six measurable features of craniofacial morphology for 13 Neandertals, 233 ancient Homo Sapiens, and 83 modern humans to see where Neanderthal features like prominent brow ridges showed up most strongly.

Common features don’t always indicate shared ancestry, since local conditions also play a role. Different species may produce the same evolutionary response to intense cold, for example, so commonalities might not indicate shared inheritance.

However, once the authors allowed for influences like this they found certain facial features “retained evidence of inbreeding with Neanderthals” generations later.

During both the middle and late Palaeolithic era, the Near East and northeast Africa were populated by people whose features place them between Neanderthals and modern humans, suggesting considerable dual inheritance. Any subsequent hybridization in Europe appears to have left much less of a mark.

“This was an exploratory study,” Churchill said. “And, honestly, I wasn’t sure this approach would actually work – we have a relatively small sample size, and we didn’t have as much data on facial structures as we would have liked. But, ultimately, the results we got are really compelling.”

Expanding the sample from the eras when Neanderthals still existed or had only recently disappeared will be a challenge. However, Churchill and Ross point out there are plenty of human skulls of intermediary age that can help track the distribution of Neanderthal genes before increased travel mixed things up. In particular, they want to study the features of the Natufians, who lived at the eastern edge of the Mediterranean 11,000 years ago and may have been particularly direct Neanderthal descendants.

We don’t know enough about Denisovan facial features to replicate the work for them, but a similar project might help settle the question of our relationship to Homo naledi.

Source Link: Fossil Skulls May Reveal Where Neanderthals And Modern Humans Mated