A new astronomical instrument has had its first outing observing the velocities of colliding galaxies in the famous Stephan’s Quintet. It has revealed the rate at which one of these galaxies is crashing through the others, and the consequences, which astronomers have likened to the sonic boom created by a jet fighter exceeding the speed of sound.

Stephan’s Quintet is a group of galaxies that have been a prime testing ground for theories of galactic motion. As the name suggests, their discoverer, Édouard Stephan recognized there are five of them, despite two being so close it’s easy to mistake them for one. Stephan was working four decades before galaxies were revealed to be objects outside the Milky Way, so he did not know what he was looking at, but could still see that this was something special.

Four of the galaxies Stephan saw are interacting with each other, and are expected to eventually form a single supergalaxy far in the future. For the moment, one of these, known as NGC 7318b, is acting like a wrecking ball, plowing through the others at relative speeds of 0.3 percent of the speed of light – which sounds more impressive as four times as fast as the Sun orbits the Galactic Center.

Stars are so small compared to the space between them that old galaxies can pass through each other with little disturbance. However, when there is still plenty of gas that has not yet turned into stars, as is the case for members of the Quintet, gas clouds crash together.

“Dynamical activity in this galaxy group has now been reawakened by a galaxy smashing through it at an incredible speed of over 2 million mph (3.2 million km/h), leading to an immensely powerful shock, much like a sonic boom from a jet fighter,” said Dr Marina Arnaudova of the University of Hertfordshire in a statement.

“Since its discovery in 1877, Stephan’s Quintet has captivated astronomers, because it represents a galactic crossroad where past collisions between galaxies have left behind a complex field of debris,” Arnaudova noted. Consequently, the group made a perfect target for the first observations of the William Herschel Telescope Enhanced Area Velocity Explorer (WEAVE), a wide-field spectrograph that has been added to the 4.2-meter (13.8-foot) optical William Herschel Telescope at La Palma.

“As the shock moves through pockets of cold gas, it travels at hypersonic speeds – several times the speed of sound in the intergalactic medium of Stephan’s Quintet – powerful enough to rip apart electrons from atoms, leaving behind a glowing trail of charged gas, as seen with WEAVE,” Arnaudova said. The word “several” understates the case – Arnaudova and her team estimated the shockwave is traveling more than 25 times the speed of sound in the gas.

The shock weakens, however, as it moves into regions of hot plasma, dropping to about four times the speed of sound and producing mostly radio waves, rather than a more energetic part of the electromagnetic spectrum. These radio waves are, however, ideal for detection with instruments such as the Very Large Array, whose output has been combined with that of WEAVE.

Weaving in the observations of other telescopes that have also looked at the famous Quintet, including the JWST, allowed the team to locate where the shock is occurring within the galaxies more precisely than ever before.

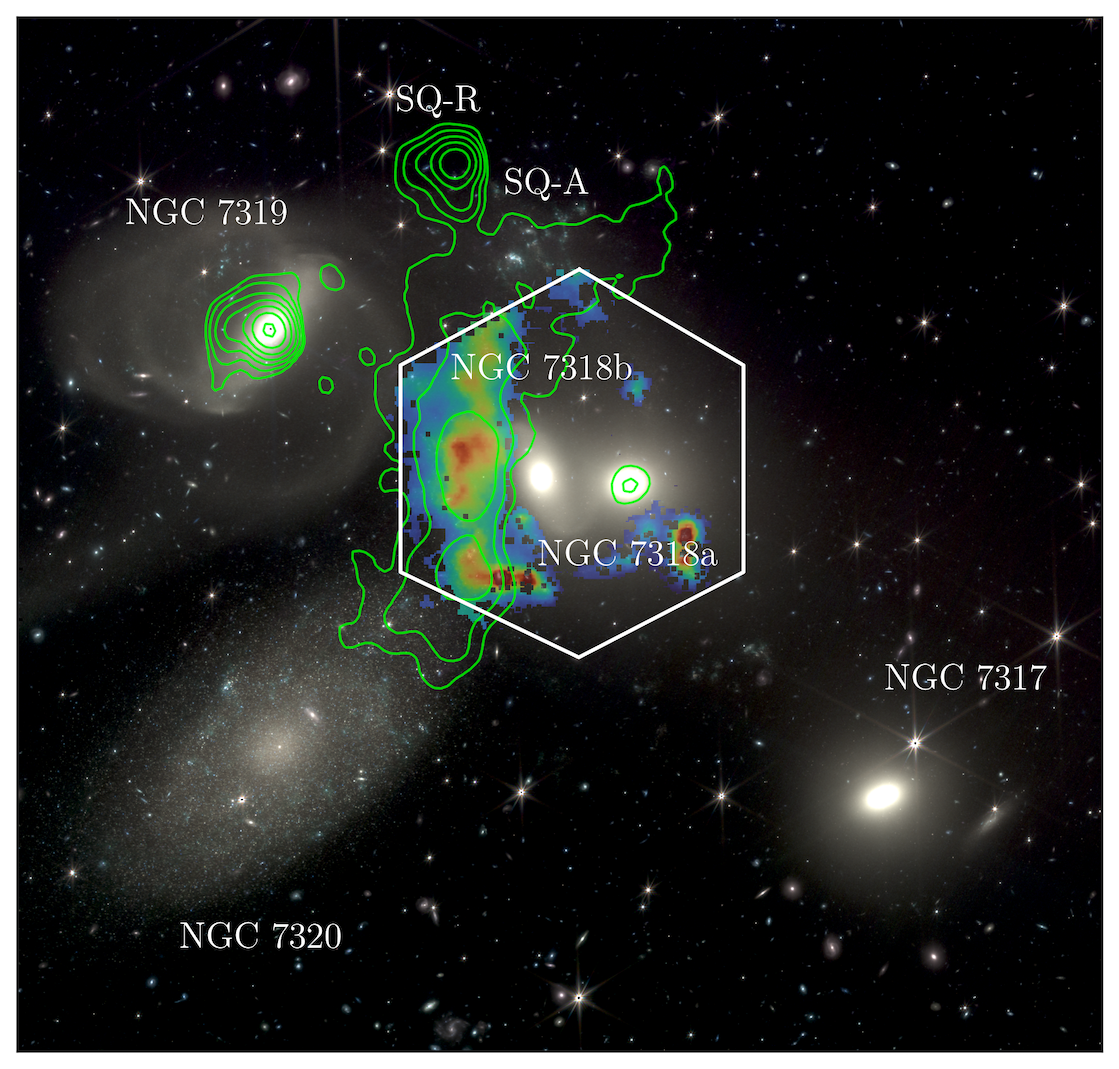

The image created by combining WEAVE’s observations with green contours provided by the Low Frequency Array. Rotated relative to the JWST image at the top.

Although the relative velocities between the NGC 7318b and the others are much greater, Arnaudova and co-authors think there are lessons from the Quintet’s interactions for the way the Milky Way will swallow the small galaxies that now orbit it. Similarly, by seeing these collisions live, we can get a better idea of the Milky Way’s past consumption of some small galaxies, and partial swallowing of others.

Collisions like this also act to stimulate the formation of stars out of gas that might otherwise have survived for billions of years without condensing. With NGC 7318b taking on several galaxies at once, there is plenty of potential for star formation, with most of it currently happening in the area known as SQ-A at the shock’s northern end. Looking closely, it is possible to see this area is bluer than the rest of the Quintet because of the hot young stars there.

The brightest of Stephan’s original five (top in the JWST image, bottom left in WEAVE) is less than a fifth the distance from us as the others, and is therefore not involved in these shenanigans. Nevertheless, the name Quintet is accurate. There’s a smaller fifth galaxy NGC 7320c, which from our perspective is hiding behind the bright one we immediately notice. Although currently some way off from the others, NGC 7320c has had encounters with the other galaxies in the past, and therefore helped shape their dynamics.

The study is Open Access in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Source Link: Galaxies Colliding At 3.2 Million Kilometers Per Hour Create A Star-Forming “Sonic Boom”