The sharp rise in parental age, particularly in the industrialized world, has been one of the most noticeable demographic changes of the last century, reflecting our greatly increased lifespans. Yet the shift is not quite as unprecedented as people may have assumed, new evidence suggests. During the Ice Age, parents, particularly fathers, were much older than for most of the agricultural era.

Unless a mother died in childbirth, fossils don’t reveal parental age. Consequently, this seemed to be one aspect of prehistory that anthropologists could only guess at by extrapolating from surviving hunter-gatherer societies.

Professor Matthew Hahn of Indiana University has changed that, with the announcement in Science Advances that the ages of our ancestors’ parents at the time of conception are encoded in our DNA. Each child has 25-75 new (de novo) mutations in their DNA, along with many that appeared earlier in their ancestry. Most are harmless, or at least only very slightly damaging, and provide a record of where we came from. Hahn and co-authors noted the kinds of mutations change as parents age.

“Through our research on modern humans we noticed that we could predict the age at which people had children from the types of DNA mutations they left to their children,” Hahn said in a statement. “We then applied this model to our human ancestors to determine what age our ancestors procreated.”

“These mutations from the past accumulate with every generation and exist in humans today,” added first author Dr Richard Wang. The authors could even track which mutations came from which parent thousands of generations back.

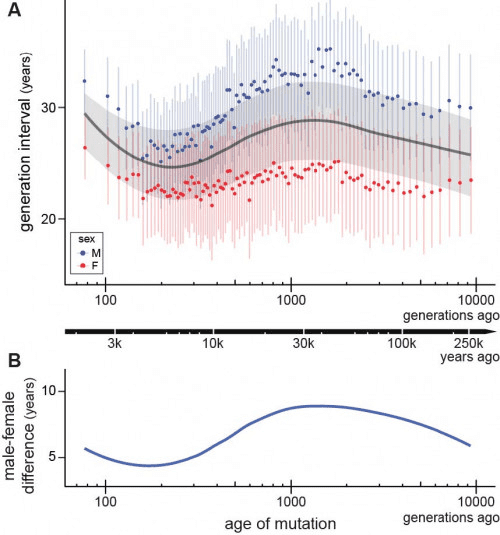

On average, Hahn, Wang, and co-authors found, conception has occurred at 26.9 years over the course of our species’ existence: 30.7 years for the father and 23.2 years for the mother. That figure hides a lot of variation, however, as the chart below shows.

Estimates of the ages of fathers (blue) and mothers (red) at the time of conception for human ancestors from going back 10,000 generations (top) and the average age gap between men and women (bottom). Image Credit: Wang et al./Science Advances

The results confirm that at all times fathers have, on average, been older than mothers, but the size of the gap has shifted fairly substantially between eras. The recent shift is easy to explain: when people expected to die in their 40s or 50s of diseases that have now become rare, there was a strong incentive to get on with having children early. Longer life spans make waiting less risky, effective contraception makes it less of a sacrifice, and increased educational opportunities for women make it financially advantageous.

What’s not as obvious is the reasons for the shift to earlier parenthood accompanying the spread of agriculture, nor the apparent spike in paternal ages around 38,000 years ago, preceding the Last Glacial Maximum. Intriguingly, until relatively recently, generation times were more than six years shorter for Asian and European populations than for African counterparts. Larger samples may enable more detailed breakdowns by region.

Although mutations in DNA sequences have been used to estimate parental ages before, the methods used only allowed averaging over thousands of generations and did not distinguish by parental sex. By using the distribution of 25 million de novo mutations identified by the 1000 Genomes Project to estimate when they arose, Hahn and Wang claim their method is far more precise.

The findings are a side quest to the team’s primary topic; gaining a more precise understanding of the number of mutations parents pass on to children. It was only when the authors compared the numbers they were getting with those for other mammals that they noticed patterns based on age and wondered if these could be put to use. Their conclusions fit well enough with what we know from written records to make the authors confident in their technique, while revealing information we couldn’t get by other means.

The paper is open access in Science Advances.

Source Link: Genetics Reveals Parents' Age At Conception Over The Last 250,000 Years