If your loyalty is to mammal-kind against rampaging reptiles, you’ve got one more reason to care about global warming. The reason reptiles, including the dinosaurs, got the jump over mammals and our ancestors has been attributed by new research to a long period of warming, not a pair of mass extinctions as previously thought.

The early Triassic era saw a rapid rate of reptile evolution. Creatures such as archosaurs came to dominate the lands, only to be pushed aside by their fellow reptiles the dinosaurs. These events followed the greatest mass extinction in Earth’s history, the Permian-Triassic extinction event (PTE), also known as the Great Dying, when an estimated 86 percent of animals went extinct.

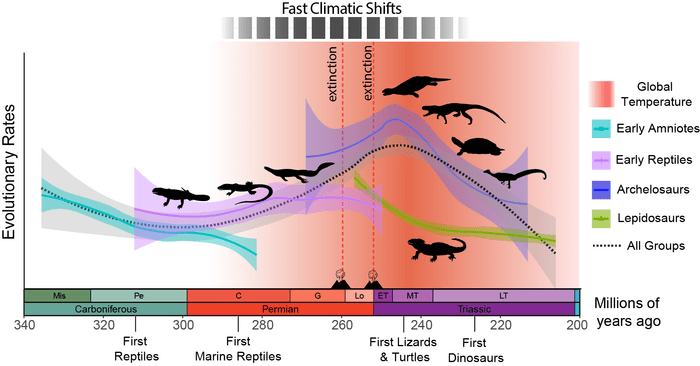

Mass extinctions create great opportunities for survivors, and paleontologists have attributed the reptile take-over to the space created by the PTE, plus a smaller calamity nine million years before. Certainly, the first crocodiles, lizards, and turtles all appeared in the Triassic, along with now-extinct major reptile groups. However, a paper in Science Advances presents evidence the roots of the reptiles’ rise lie earlier, in late-Permian temperature fluctuations.

Mammals have only been the dominant class on Earth since the asteroid cleared the way for us 66 million years ago. However, our ancestors, the synapsids, had a turn of their own during the Permian era. It makes intuitive sense the reptile era began with an extinction event as well as ending with one. The PTE’s causes are much debated, but there’s no question the synapsids were a major casualty.

However, the paper notes that although the greatest rate of reptile diversification came after the extinctions, there was already an upswing in new reptile species beforehand. Moreover, the timing of their appearance was not random.

“We found that these periods of rapid evolution of reptiles were intimately connected to increasing temperatures. Some groups changed really fast and some less fast, but nearly all reptiles were evolving much faster than they ever had before,” said lead author Dr Tiago R Simões of Harvard University in a statement.

The peak of new reptile species came in the early Triassic, but the upswing had started earlier, and coincided with temperature fluctuations and picked up between the two major extinctions: Image Credit: Tiago Simoes

Co-author Professor Stephanie Pierce noted it was not just the number of new species that coincided with bouts of warming, but the diversity of the body shapes and ecological niches filled. “This process started long before the Permian-Triassic extinction, since at least 270 million years ago, indicating that the diversification of reptile body plans was not triggered by the P-T extinction event as previously thought, but in fact started tens of million years before that,” Pierce said.

Being unable to regulate their own body temperatures, reptiles are much better suited to hot climates than cold ones, although at least some dinosaurs managed to warm their blood enough to occupy the poles. However, the authors think it is not as simple as more heat equalling more reptiles.

“Small-bodied reptiles can better exchange heat with their surrounding environment,” Simões said. “The first lizards and tuataras were much smaller than other groups of reptiles, not that different from their modern relatives, and so they were better adapted to cope with drastic temperature changes. The much larger ancestors of crocodiles, turtles, and dinosaurs could not lose heat as easily and had to quickly change their bodies in order to adapt to the new environmental conditions.”

Consequently, the relatively rapid fluctuations of the Permian favored small reptiles; larger ones benefited from the consistent heat in the early Triassic. During the hottest parts of the Permian, the tropics got so hot reptiles couldn’t get very large there without moving into the oceans.

The authors think this early reptile diversification has been overlooked because land records are sparse. Marine fossils are more abundant, making them the focus of mass extinction studies. The paper used the largest database of appearances and extinctions for early reptiles, synapsids, and predecessors ever made to address this.

Source Link: Global Warming Gave Us Hundreds Of Millions Of Years Of Reptile Domination