Seven years ago, the world was both horrified and enthralled by the announcement of a giant “fatberg” in the London sewers composed of human waste, cooking fat, sanitary products and items that carry specific instructions not to be flushed. That case drew attention to a growing problem worldwide, but two chemical engineers think they have the solution in the form of a coating for sewers.

The fatberg that brought the concept to public attention was 250 meters (820 feet) long and weighed 130 tonnes (286,600 pounds). In the era of wildlife-based measuring units, this was noted to be the equivalent of 19 adult African elephants. Twenty elephants sounds better, and that’s probably accurate in drought years.

Not surprisingly, this event caused serious problems for the London sewage system and the unfortunate individuals who had to clean it up. Subsequent examples have turned up even in small towns and inspired pleas to not flush items that contribute to the build-up. It doesn’t seem to be working, judging by the fact the record was smashed just a year later.

If begging people to only use their toilets for the intended purpose doesn’t work, an engineering solution might. According to Dr Sachin Yadav and Dr Biplob Pramanik of RMIT University, calcium is a key component of fatbergs, causing the other ingredients to coagulate. The calcium is not primarily from people consuming a high-dairy diet, but leaches into the system from concrete sewer walls.

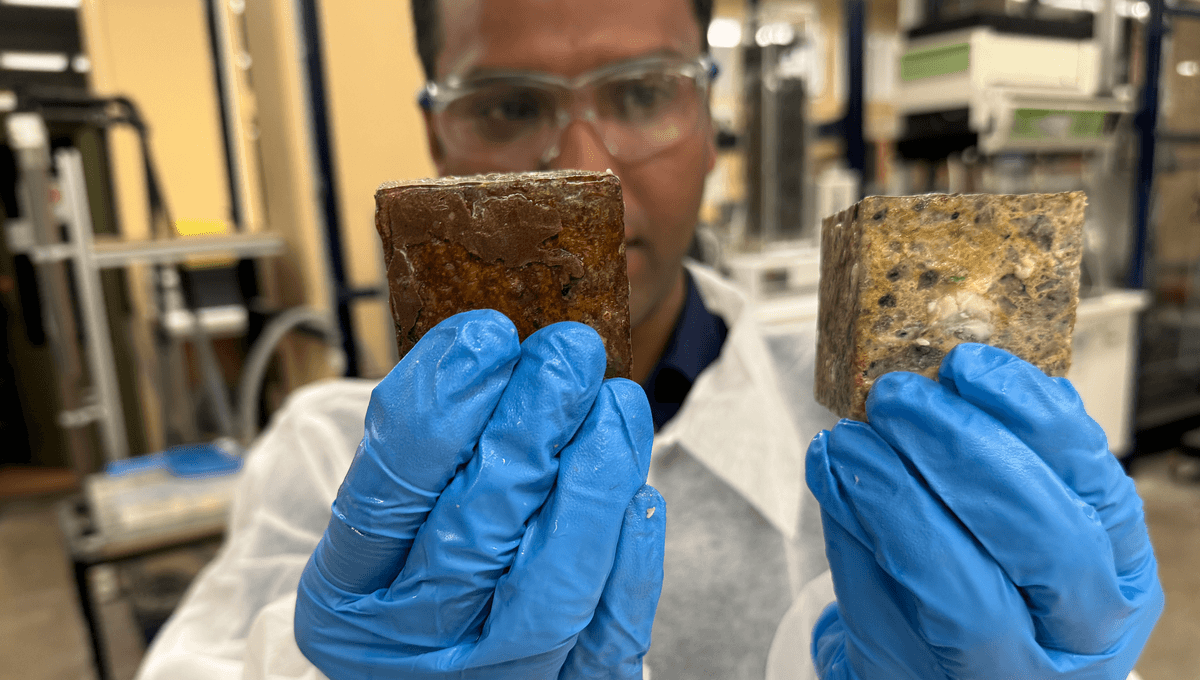

Yadav and Pramanik created a zinc-polyurethane hybrid coating that in a trial reduced calcium leaching by 80 percent, making the concrete more stable. More importantly, in a model system, the coating reduced the build-up of fat, oil, and grease (FOG), the major components of fatbergs, by 30 percent. “The reduction of fat, oil, and grease build-up can be attributed to the significantly reduced release of calcium from coated concrete, as well as less sticking of FOG on the coating surface compared to the rough, uncoated concrete surface,” Pramanik said in a statement.

Yadav told IFLScience the work was a “proof of concept”, and the pair are now aspiring towards 90 percent calcium reductions and even less FOG solidification.

We can all see that it’s better not to have our sewers blocked, for most this is a problem that really is ‘out of sight, out of mind’. However, fatbergs cost us all. The blockages they create are estimated to add $25 billion to sewage maintenance and rehabilitation a year in the United States alone. By building the first modern sewage system, London missed out on the chance to learn from others, and now has particularly large costs per capita. The problem is getting worse, which Yadav told IFLScience is partially a result of increased dishwasher use adding more long-chain fatty acids to the contents of sewers.

The secret to Yadav and Pramanik’s success is to replace coatings like magnesium hydroxide, which have been used in recent decades to prevent corrosion in sewers, with triple-bonded Zn-polyurethane. Yadav told IFLScience that existing methods to coat sewers’ internal walls can be easily adapted to use their product instead.

The coating is not only stable up to temperatures of 850°C (1,562°F), it is also self-healing: when Yadav scratched the coating, it partially restored itself, and the pair hope to improve this further. Yadav acknowledged that “Zinc is to some extent toxic,” but claims the study demonstrated none of the metal leaked into the sewers. There’s rivalry at RMIT though, with another team developing an alternative solution – concrete that has no cement, and therefore leaches no calcium.

The coating may not solve the problem on its own, so Pramanik is also developing a grease interceptor to supply restaurants and other major sources of FOG. An autopsy on the original fatberg found around 90 percent of it was cooking oil.

Someday soon, Fatberg the Musical may be a historical piece, as well as science fiction.

The study is open access in the Chemical Engineering Journal.

Source Link: Goodbye Fatbergs: There’s Light At The End Of The Sewer