Tectonically, Greenland sits on the North American Plate. But when it comes to history, politics, society, and culture, whether it truly “belongs” to North America is a much more complex question.

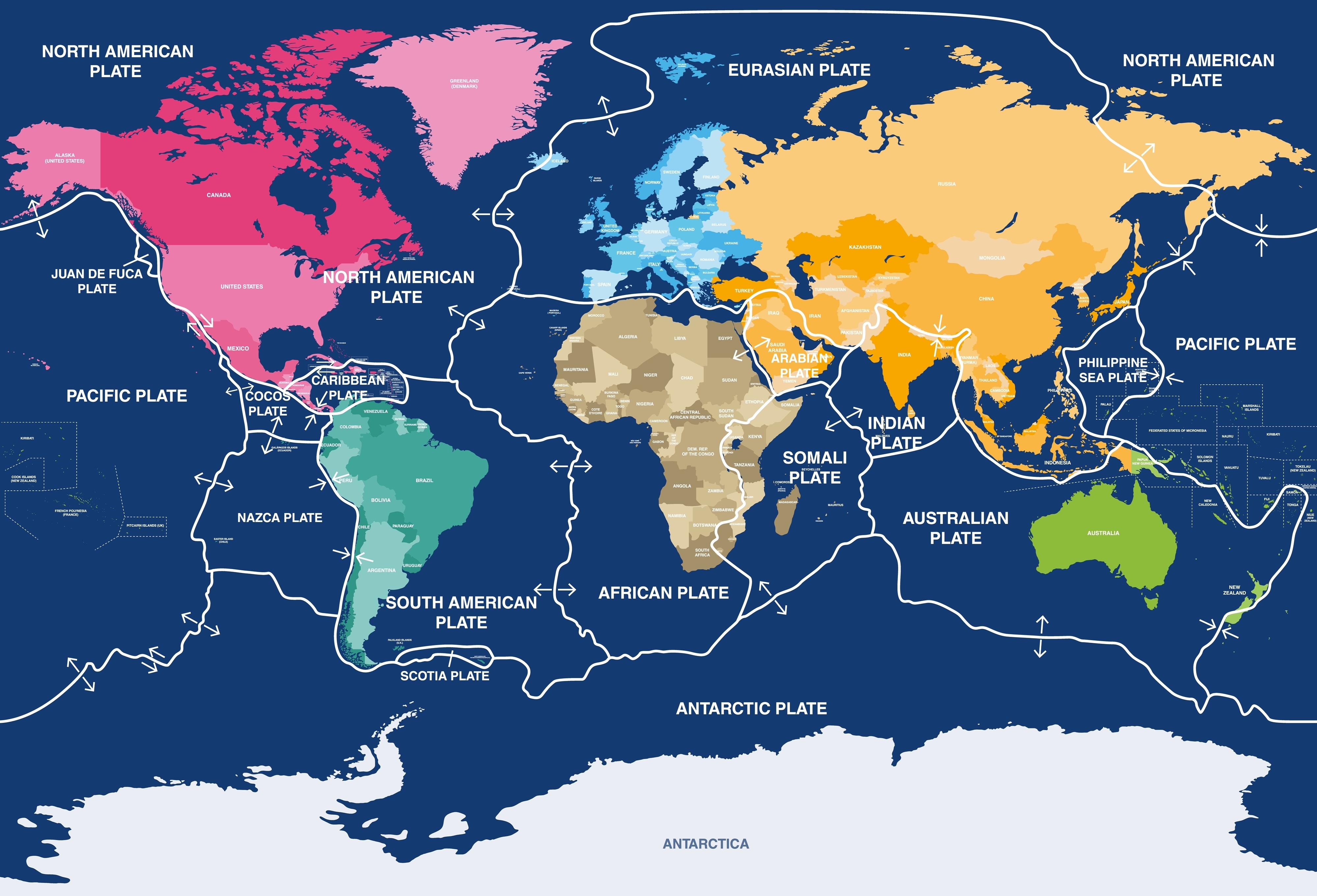

The North American Plate is a tectonic plate containing most of the US, Canada, and Mexico, as well as Cuba, the Bahamas, the extreme northwestern edge of Siberia, northern Japan, and parts of Iceland and the Azores.

Despite being tied together beneath the surface, these regions diverge sharply above it. Iceland and the Azores are politically and culturally European. Cuba is firmly part of Latin America, while the Bahamas belong to the Caribbean. Northwestern Siberia and northern Japan are unmistakably Asian in geography and identity.

Curiously, not even all of the United States rests on the North American Plate. Hawaii sits in the middle of the Pacific Plate, as do large parts of California that are west of the San Andreas Fault.

Tectonic plates, therefore, don’t directly line up with the boundaries of countries or continents (which itself is a very subjective concept).

A world map showing the main tectonic plates on Earth’s surface.

Image credit: brichuas/Shutterstock.com

Things get especially murky when it comes to historical and political connections. Greenland has a complex identity shaped by a unique blend of internal and external influences, much like any country. It has ancient historical and cultural links to North America through the Greenlandic Inuit and other Indigenous populations who share a common ancestral lineage with Native Americans.

Modern connections to North America, however, are more limited. One notable example is Camp Century, a US military research base built in Greenland during the Cold War. Operated between 1959 and 1967, it reflected America’s strategic interest in this part of the Arctic, but it was a brief (and ill-fated) foray, rather than a lasting link.

Politically, it’s an autonomous territory of Denmark, which means its modern governance and some cultural ties are deeply rooted in Europe. Danish is widely spoken alongside Greenlandic, and the island’s education, legal, and healthcare systems are modeled after Scandinavian frameworks. It simultaneously maintains thousands of years of Inuit heritage, and Indigenous culture still shapes the daily lives of people across the island.

The Trump administration has recently doubled down on the claim that the US should have direct control over Greenland, citing the island as vital to national security. In December 2024, shortly before his second term in office, then President-elect Trump wrote on social media: “For purposes of National Security and Freedom throughout the World, the United States of America feels that the ownership and control of Greenland is an absolute necessity.”

It sounded like an outlandish plan to many outsiders, but the US has persistently flirted with the idea throughout its short history. Nevertheless, Greenlandic authorities have continuously defended the nation’s right to self-determination, stating the country is “not for sale”. Recent polls have suggested that the vast majority of people in Greenland want to become independent from Denmark – and they certainly have no desire to be part of the US.

In short, Greenland defies easy classification. Geologically North American, historically connected to Indigenous Arctic peoples, politically linked to Europe, and culturally somewhere in between, it resists being confined to any single continental identity. Whether its future will be shaped by its own people, its tectonic foundation, or the geopolitical interests that orbit it remains to be seen.

Source Link: Greenland Is Already Part Of North America, But Only In Terms Of Tectonic Plates