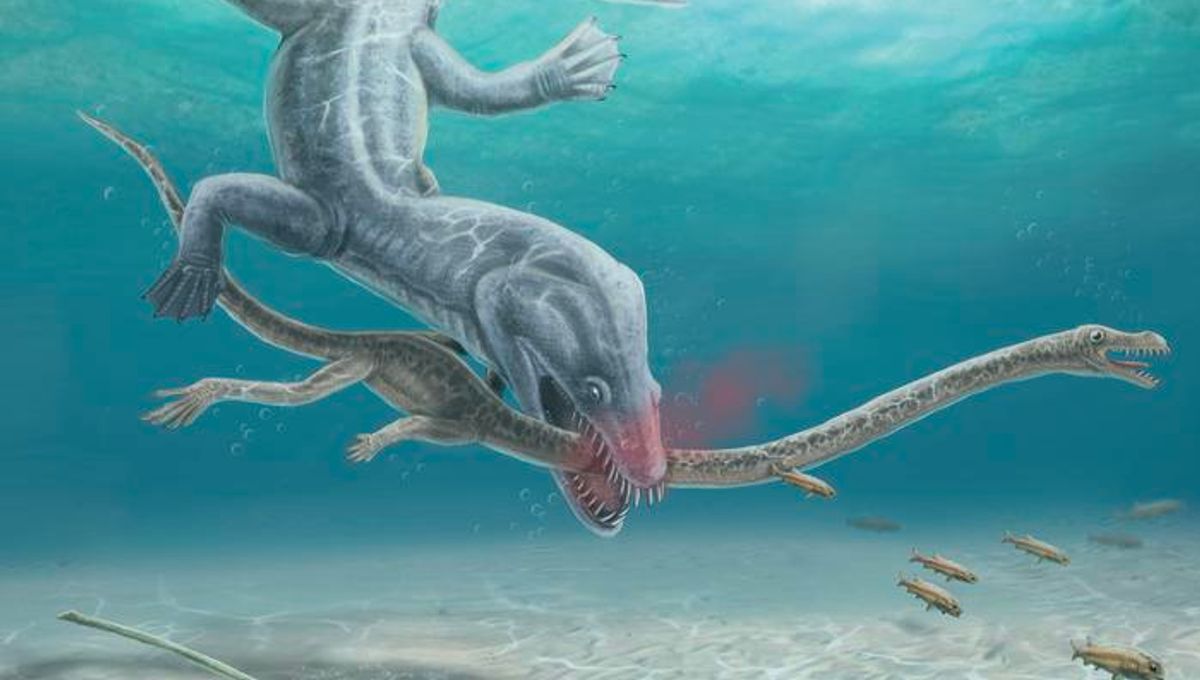

The first evidence has been produced of savage attacks on the elongated necks of ancient marine reptiles, confirming a long-term suspicion of palaeontologists, and a favorite subject for paleoart.

Long necks were much in fashion when dinosaurs ruled the Earth. On land there were the sauropods, whether small or vast. In the oceans necks got even longer, at least relative to body length. The benefits of such extensions are obvious, but who has not wondered if they were also a point of vulnerability? Turns out they were.

In a new study, Drs Stephan Spiekman and Eudald Mujal, both of the Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde Stuttgart, report that the necks of two Tanystropheus fossils of very different sizes met the same end, severed in the midsection. No sign of either animals’ body has been found.

Tanystropheus was one of many marine reptiles that independently evolved necks worthy of the Loch Ness monster, probably to capture squid and shellfish from the seafloor. Indeed it was something of a trendsetter, getting there in the Triassic, millions of years before plesiosaurs. Although a predator, it seems Tanystropheus was anything but apex, with several much larger predators prowling similar waters.

Large Tanystropheus had necks about 3 meters (10 feet) long, at least as long as their body and tail combined.

“Paleontologists speculated that these long necks formed an obvious weak spot for predation, as was already vividly depicted almost 200 years ago in a famous painting by Henry de la Beche from 1830,” Spiekman said in a statement.

However, as with most large animals, Tanystropheus fossils are usually composed of just a few bones, making it hard to determine the cause of death. Prior to Spiekman’s examination of two Tanystropheus fossils from the Swiss/Italian border for his PhD, there was no evidence of this sort of attack for any long-necked marine reptile, let alone this specific genus.

After examining the two specimens, one of which would have been 6 meters (20 feet) long, while the other was a quarter that length, Spiekman sought assistance from Mujal, an expert in ancient bite marks. Mujal considers both specimens clear cases, where even the angles of attack – from above and in one case the rear – can be identified. Both breaks occurred in the necks’ thin midsections.

“Something that caught our attention is that the skull and portion of the neck preserved are undisturbed, only showing some disarticulation due to the typical decay of a carcass in a quiet environment,” Mujal said. “Only the neck and head are preserved; there is no evidence whatsoever of the rest of the animals. The necks end abruptly, indicating they were completely severed by another animal during a particularly violent event.”

In both cases the predator was probably too busy feasting on the body to worry about the head and neck, and these were covered in mud while still held together by soft tissues. “Although this is speculative, it would make sense that the predators were less interested in the skinny neck and small head, and instead focused on the much meatier parts of the body,” Mujal added.

Although their body plan spelled doom for these Tanystropheus individuals, it apparently worked quite well most of the time. Four species have been identified, and their fossils are found widely over Europe, Asia, and North America from the middle Triassic.

Despite their superficial resemblance to plesiosaurs, Tanystropheus’s 13 hyper-elongated vertebrate gave them a much narrower and stiffer neck than others that took a similar shape. “In a very broad sense, our research once again shows that evolution is a game of trade-offs,” Spiekman said. “The advantage of having a long neck clearly outweighed the risk of being targeted by a predator for a very long time.”

Although Tanystropheus has generally been seen as a marine animal, this is a matter of some controversy, with some palaeontologists arguing its tail was ill-suited to swimming, and instead proposing it lived on land. That’s already been refuted, however, and the authors of this paper have no doubt on this question: the spacing of the teeth marks on the larger Tanystropheus indicate the killer was an even bigger marine reptile.

The study is published in Current Biology.

Source Link: Having A Noodle Neck Got You Decapitated Back In The Triassic, Fossils Confirm