Shards retrieved from the alchemy laboratory of 16th Century scientific pioneer Tycho Brahe have traces of unexpected elements, not truly discovered for almost two more centuries. This and other elemental traces may give some insight into what Brahe was doing in his basement laboratory, although many questions may never be answered.

In an era when science was largely the preserve of a tiny few with the good fortune to be able to devote themselves to study, the boundaries between different fields meant less than today. Tycho Brahe is remembered today as the greatest observational astronomer before the invention of the telescope. The unprecedented precision he achieved in his measurements of planetary positions proved essential to Johannes Kepler’s explanation of planetary motion; which in turn laid the foundations for Newton and missions to other planets. One of the most prominent craters on the Moon is named in his honor for this reason.

Brahe was also interested in alchemy. Unlike the more famous alchemists, he did not believe it was possible to turn base metals into gold, instead seeking to use them to cure diseases like plague and syphilis. Mercury, for all its devastating side effects, was the one treatment available for syphilis before penicillin that sometimes worked. Brahe’s cure for the plague was used by his patron, Emperor Rudolph II.

Alchemists seeking to make gold were notoriously secretive regarding their methods – they knew the value of their products would crash if everyone else could make them too. Some of this may have rubbed off on Brahe, but secrecy came naturally to him, he nearly derailed his scientific legacy by making Kepler beg for fragments of his astronomical observations.

Unsurprisingly, we know little about Brahe’s medicines. What recipes survive include using theriac, a popular medication of the day that included up to 60 ingredients, to which Brahe added even more, after complicated processing.

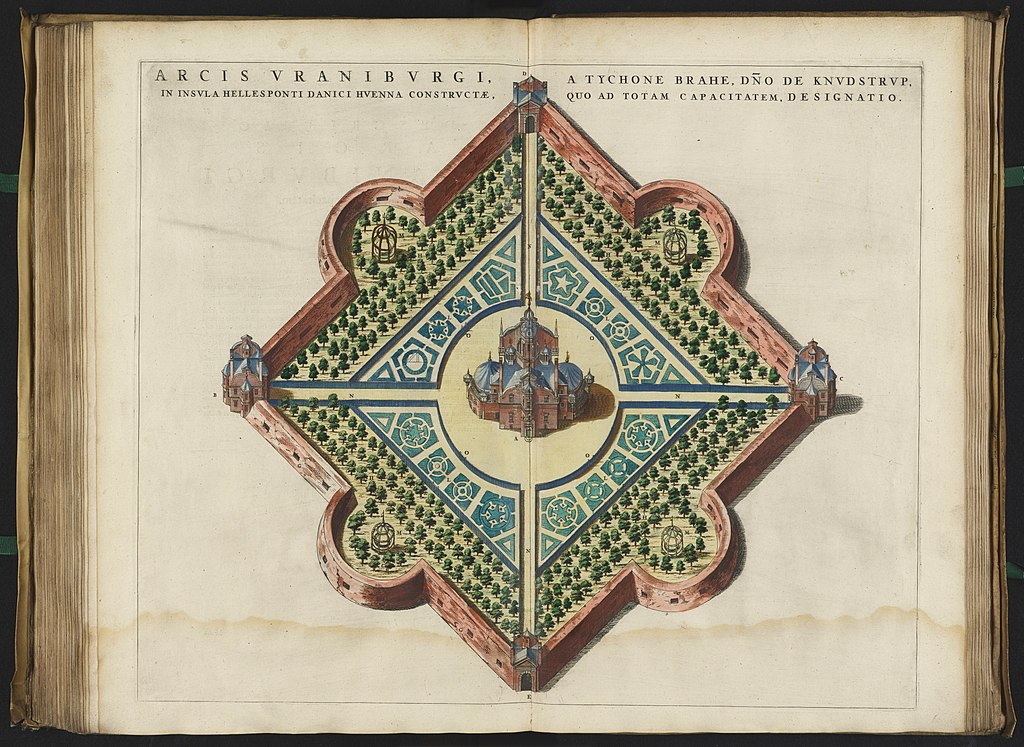

Excavations in 1988-90 at Uraniborg, Brahe’s home, may change this by revealing shards of pottery and glass. The palace was destroyed by royal decree after Brahe’s death in 1601, but he published detailed plans and it is thought these shards are from the basement where he attempted alchemy away from prying eyes.

Uraniborg Brahe’s palace was both a luxurious home and the world’s most advanced astronomical observatory, with an alchemy laboratory in the basement.

Four glass and one pottery shard have been subjected to chemical analysis. All but one glass shard shows enrichment in nickel, copper, zinc, tin, antimony, tungsten, gold, mercury, and lead relative to background levels, indicating each was used in experiments. Four of these metals are ingredients in Brahe’s surviving recipes, and the others were of interest to alchemists of the day.

“But tungsten is very mysterious,” said Professor Kaare Lund Rasmusssen of University of Southern Denmark in a statement. “Tungsten had not even been described at that time, so what should we infer from its presence on a shard from Tycho Brahe’s alchemy workshop?”

It was another 180 years until fellow Scandinavian Carl Wilhelm Scheele described the properties of pure tungsten. Either traces happened to be in the minerals Brahe was using and were caught on the shards, or Brahe was far ahead of his time.

The second idea, while exciting, is unprovable. It would also be considered unlikely for most experimenters. However, given what we know of Brahe’s astronomical talents, it would not be completely unexpected if he was also a chemist of rare skill.

Moreover, tungsten was not entirely unknown before Scheele. Decades before Brahe, German mineralogist Georgius Agricola reported that tin ores from Saxony contained a mystery ingredient, which he named Wolfram, that made them hard to smelt. That name, meaning Wolf’s froth in German, is the reason tungsten has the chemical symbol W today, to the annoyance of generations of school students and the delight of quiz masters.

“Maybe Tycho Brahe had heard about this and thus knew of tungsten’s existence. But this is not something we know or can say based on the analyses I have done. It is merely a possible theoretical explanation for why we find tungsten in the samples,” Lund Rasmussen said.

If Brahe was aware of tungsten, we don’t know, and probably never will, whether he got closer to purification than his predecessors. If so, publication of his work might have represented a significant advance for chemistry, short-circuiting the long wait that occurred instead. Given tungsten’s usefulness, for example in making harder steel (and pseudo-lightsabres) it might have led to many practical applications occurring centuries earlier.

To Brahe, alchemy and astronomy were not as distinct as they seem to us. In 1588 he wrote a letter in which he claimed associations between each moving heavenly body and a corresponding metal and organ. For example, he linked the Moon, silver and the brain while thinking Venus was connected to copper and the kidneys.

Rasmussen has previously analyzed samples of Tycho’s own hairs, indicating he may have consumed his own medicines containing gold, which he associated with the heart and Sun.

Blurring the picture further, the elements present on the shards may not have been the result of Brahe’s own work. His sister and brother-in-law were also keen alchemists, and visited Uraniborg frequently. With Brahe’s laboratory possibly the finest in Europe, they may have borrowed it for their own work.

The study is open access in Heritage Science.

Source Link: Hidden Elements Found In The Alchemy Laboratory Of One History’s Greatest Astronomers