A documentary about the exploration of possibly the most astonishing archaeological site of close human relatives makes the biggest assertions yet regarding Homo naledi, the deeply puzzling species found there. If true, the claims made by the team excavating the site would transform how we see ourselves and our place in the evolutionary tree. Many other experts in the field are not just unconvinced, however; they are very unhappy about the way the research is being presented to the public while bypassing the traditional scientific channels.

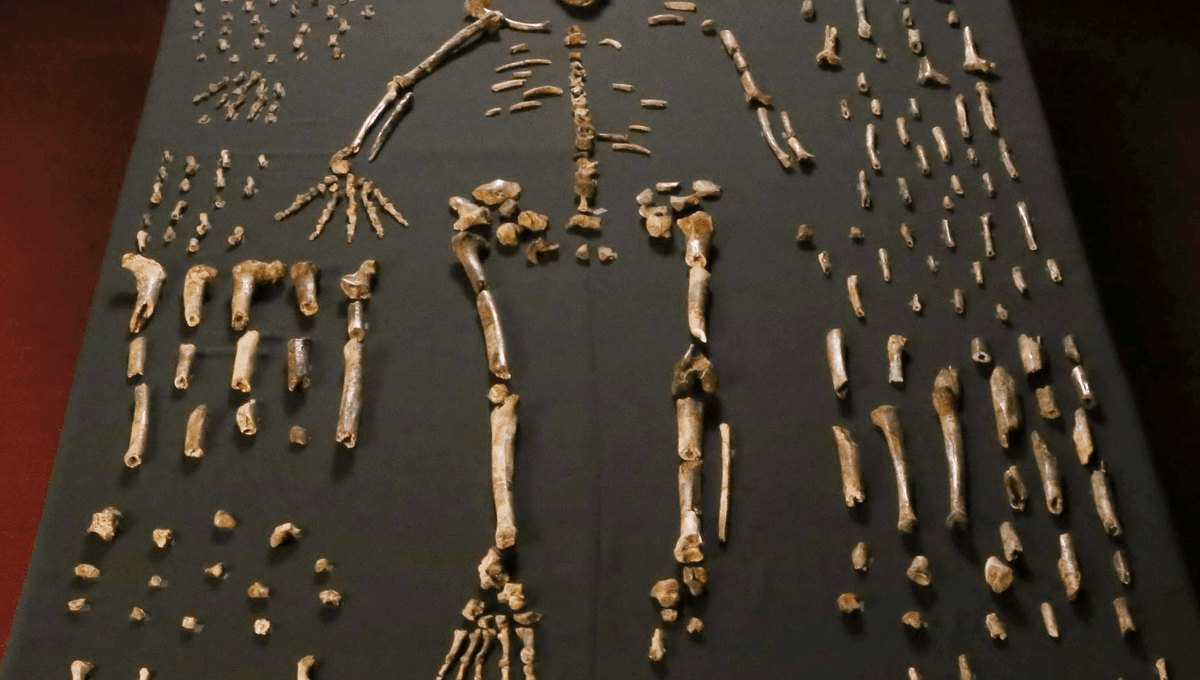

In 2015, Professor Lee Berger of Witwatersrand University stunned the world with the announcement of a new species of hominin he named Homo naledi. From the start the discovery stood out: in a field where it’s rare to find more than two or three bones from a previously unknown species, remains from at least 15 individuals had been found in the Rising Star Cave, South Africa, all from a species whose existence had not even been guessed at before.

Moreover, H. naledi has a brain not much larger than a chimpanzee’s, but fingers and toes much like our own. The possibility of a Piltdown-man type hoax has been dismissed, but the combination of features is certainly unexpected. Initially Berger thought H. naledi lived millions of years ago, as their brain size suggested, but subsequent dating has demonstrated they overlapped with Homo sapiens, some 250,000 years ago.

Important as we consider our hands, it’s our brain size, hard-won over five million years of evolution, that really separates us from other species. Consequently, most anthropologists assumed H. naledi’s behavior would be more like that of a modern ape than ourselves, but Berger has challenged that from the start.

Two months ago, in a series of three papers, Berger made staggering claims for H. naledi: that they buried their dead, used fire, and carved the world’s oldest artworks into a cave pillar. Even our own ancestors, with brains almost as large as our own, were probably not doing most of these things at the time.

A documentary released on Netflix over the weekend expands on these claims, including the suggestion that one of the bodies in the cave was buried holding a stone tool. As team members note, in the Stone Age good tools were valuable; it would be unlikely one would be wasted by leaving it with a corpse. Unless, that is, those responsible had a concept of an afterlife, and this was a predecessor of grave goods, like the swords kings and warriors were once buried with on the expectation they would still need them.

The documentary provides a fascinating insight into the challenges of excavating such a difficult location, but it makes no pretense at balance. No paleoanthropologists outside Berger’s team are interviewed, and their responses to the papers are not mentioned.

Professor Michael Petraglia of Griffith University is one who is far from convinced. “There is no question that [we] have remains of at least 15 individuals [in the cave],” Petraglia told IFLScience. “And that is a remarkable discovery.” However, from the start Berger has made claims that Petraglia thinks lack evidence, and that has deepened recently.

Today, Rising Star is so difficult to get into that it seems as though the location of the bones could not be a coincidence. Even a smaller and more nimble species than modern humans would have needed to make a major effort to reach the innermost space if everything was as it is today, suggesting a deliberate burial chamber. The only current path is effectively impossible to follow without a source of light, and therefore fire.

However, Petraglia told IFLScience, “There are published articles that question whether the shape of the cave was the same when Homo naledi were using it as it is now.” Rockfalls may have blocked far more accessible entrances, and cracks in the roof that allowed light in. Although charcoal has been found in the cave, Petraglia said efforts to date the initial discovery had suggested it was far more recent than H. naledi, suggesting it might have been brought by Homo sapiens.

More extensive traces of fire found more recently have yet to be dated – or if they have, the results have not been published. Petraglia is critical of this, saying getting charcoal dating is now relatively quick and easy.

Similarly, no experts on rock art have been invited to study the lines Berger and co-authors claim are predecessors of those carved by Neanderthals and modern humans making the first symbolic artifacts.

Petraglia was senior author of the paper announcing the oldest evidence of deliberate burial from Homo sapiens, about a third of the age of the H. naledi fossils. He says the site lacks some of the features normally associated with burials, such as unambiguous excavation.

Petraglia acknowledges that the delicate nature of the cave and the difficulties in entering it make the site unsuited to having too many people study it. Nevertheless, he says it would be easy for the team on the ground to show the detailed images they have taken to experts who could “study them from a desktop”. This hasn’t been done, and Petraglia notes the dolomite rock on which the “carvings” are visible has a natural tendency to develop fissures with a similar appearance.

Normally these sorts of debates would be part of the cut and thrust of scientific research, even if paleoanthropologists are infamous for making them more boisterous than other fields. However, by issuing media releases while the papers were still in preprint, and now getting coverage on Netflix and National Geographic, Berger is taking the discussion to the court of public opinion. With claims this significant and emotionally engaging, there are likely to be plenty of listeners.

“I’m concerned about public perception,” Petraglia said. “Without critics out there, people will just believe.” If it turns out the claims are wrong, the field’s reputation could suffer.

Petraglia is far from alone. The Observer quotes three other scientists with similar critiques, and Science spoke to others.

Berger and his colleagues may not have convinced their peers, but skeptics are just as far from disproving the claims. Science often moves frustratingly slowly, but after a quarter of a million years, maybe we can afford to wait a few more for judgement on whether Homo naledi beat us to achieving many of the things we consider uniquely human.

Berger’s papers are published open access in eLife, including possibly the most contentious one.

Source Link: Homo Naledi Documentary Adds Fuel To Already Heated Scientific Debate