Proteins have been used to generate a material able to absorb supersonic impacts, a new study shows. The research, which is yet to be peer-reviewed, reports on how the material can absorb shots at 1.5 kilometers per second (3,355 mph) while preserving the projectile so that it can be easily removed.

The protein in question is called talin, and we previously reported on its role in a new theory of how memory works, called MeshCODE. Now, a chance conversation between a biologist and a chemist has unlocked an entirely new avenue of research to explore.

“Whilst very different from the main research in my lab on the study of talin in the MeshCODE theory and the mechanical basis of memory, this has been one of my favourite side projects and collaborations.” lead author Ben Goult, of the University of Kent in the UK, told IFLScience.

When a talin molecule is exposed to mechanical stress, switch domains within the protein’s structure unfold, effectively stretching the molecule out. As tension builds, each unfolding of a domain reintroduces some slack, lowering the tension a little bit, before it builds again, and the next domain unfolds. This process is fully reversible; once all the tension is released, the protein folds back up into its original shape. This video shows the folding and unfolding in action.

Goult happened to be discussing this with a colleague in the chemistry department at the University of Kent, Professor Jen Hiscock, when she pointed out that this amazing property of talin could lend itself to shock-absorbing applications. It sounded like the perfect opportunity for collaboration.

“After those initial discussions, we decided it would be fun to join forces on a Synthetic Biology […] project to develop talin as a shock absorber to generate novel materials constructed of talin, which we call Talin Shock Absorbing Materials (TSAMs). This was a perfect collaboration as it combined my experience on talin mechanobiology with Jen’s experience on chemistry and material science,” said Goult. “And we combined these expertise in a completely novel way.”

The first TSAM was produced by then-PhD student Jack Doolan. Large quantities of a re-engineered talin molecule, containing the first three of the switch domains, were produced and linked together into a mesh. The end result was a gel-like material called a hydrogel.

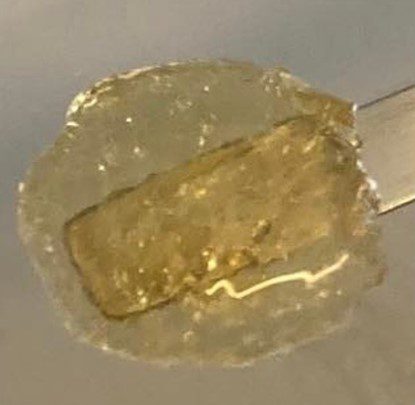

This is what the TSAM hydrogel looked like before it was subjected to the impact experiments. Image courtesy of Ben Goult.

The astrophysics department at the University of Kent is equipped with one of the fastest light gas guns in Europe, so the team used this to put the TSAM through its paces.

What they found was totally unexpected.

“When subjected to 1.5 kilometers per second supersonic shots, our TSAMs were shown not only to absorb the impact, but they also captured/preserved the projectile, making TSAMs the first reported protein material to achieve this. This preservation of the particles was very exciting to the physicists as it was the first material they had seen that captured the particles intact,” continued Goult.

This shock-absorbing power, coupled with the fact that the material is self-repairing thanks to the reversible folding/unfolding of talin, means TSAMs could have huge potential. The team is already in talks with the UK Ministry of Defence and hopes to start field tests with the material soon. Using different regions of the talin molecule to start with, they could potentially develop a suite of similar materials, all with slightly different properties.

“As well as potential roles in talin-based armour, and in the defence and aerospace sectors, such shock absorbing materials are highly sought after for the production of next generation commercial products (e.g. for mobile phone cases/running shoes/car bumpers),” Goult explained.

The history of science is littered with unintentional, serendipitous discoveries, from penicillin to microwave ovens. As Goult points out, “Perhaps soon we could all be wearing talin-based products” – and, if we are, it will all come back to one chance encounter between two colleagues in a university corridor.

The preprint of the study is available at bioRxiv.

Source Link: How Brain Protein Research Led Scientists To Develop Shock Absorbing Armor