Spider silk is incredibly strong, and their webs can be very sticky, ensnaring prey in an instant. It seems like a treacherous terrain to spend your life on, but spiders have evolved to navigate their silken traps that catch out so many other species.

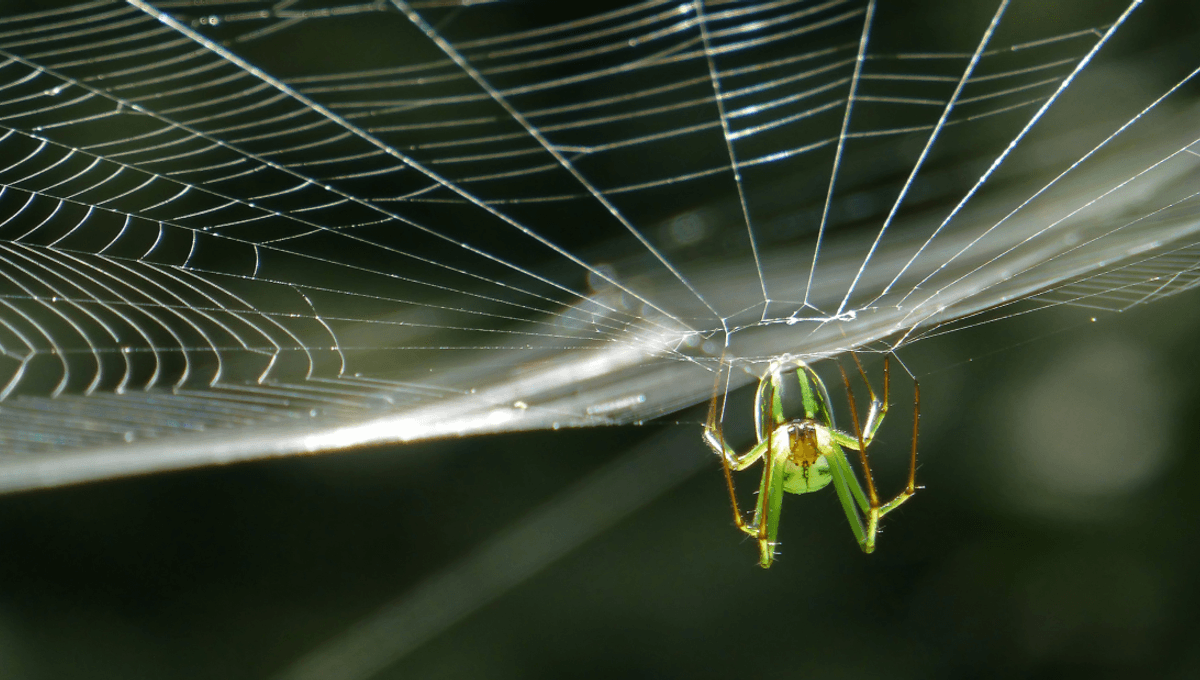

When we think about spiders getting stuck in their webs, we’re mostly talking about the orb weavers who create that classic wheel-shaped web you find slung between plants, trees – just about anything, really. These spiders are from the family Araneidae and when they build their webs, they use a combination of silk types to fulfill different functions.

Spider silk is spun from glands and depending on the type of silk it can be one of seven glands. No spider species has all seven, explains London’s Natural History Museum, but many species will have several – the orb weavers, for example, have five.

The silk leaves the gland with the aid of spinnerets that have nozzle-like structures called spigots on the end. The liquid silk exits the spider’s body either due to gravity or being pulled by a rear leg and then solidifies, and the end result can be strong, tough, or act like a cushioning (as in the case of the inner layer of egg cases). Some silk acts like cement, securing the web, and some acts as a sticky coating.

Dragline silk is a particularly handy variety that many spiders will use as a lifeline while trying to escape predators, but it can also be used to begin the basic foundation of a web. The wheel-like web is reinforced with an auxiliary spiral that helps to support the spider as it builds, but this is snipped away and replaced with a catching spiral that’s coated with blobs of a glue-like substance.

Here it seems like the spider would be at risk of getting caught in their own web, but not all of the silk will be sticky. Furthermore, specialized claws on the spider’s feet combined, with choice placement, help to keep them clear of the sticky parts. Spiders’ legs are also coated in a non-stick combo of branching hairs and an anti-adhesion chemical coating, explained Smithsonian Insider, which combined with their “fancy footwork” keeps them out of trouble.

Some spiders are so good at keeping clear of the dangerous parts of webs that they make their living off of it, as in the case of the dewdrop spider. It parasitizes the webs of orb weavers, giving rise to a fantastic shot from Wildlife Photographer Of The Year 2023. It looks as if the one-way relationship could end badly for the dewdrop, but actually, it’s the giant orb weaver that’s at risk of predation by its tiny freeloader when it molts and temporarily becomes defenseless.

And landlords think they have it bad.

Source Link: How Come Spiders Don’t Get Tangled In Their Own Webs?