The Dark Ages has a bad reputation. In fact, it’s possibly the only period of history literally named after its bad reputation: the title, as we all learn in school, is a reference to the idea that, after the Roman Empire fell in the West, everyone spent the next few centuries in the metaphorical dark – that is, stumbling about, unable to see the true shape of things, and occasionally braining themselves on the odd barber-surgeon.

But how fair is that? Were the 500 years before the Renaissance really all that bad?

Let’s shed some light on what life was really like in the so-called “Dark Ages” – and whether it was really “dark” at all.

Why was it called the “Dark Ages”?

Pretty simple answer to this one: it wasn’t. Not at the time, at least.

Look, we all get a kick out of the apparently dumb stuff our ancestors did: using tattoos as medicine, for example, or rubbing powdered owl on themselves as a cure for gout. What we don’t tend to realize so much is that those people were equally amused by – and derisive of – their own forebears.

“The term (rather like ‘The Middle Ages’ or ‘Medieval’ in Latin) was coined during the Renaissance,” explained Lucy Marten, Visiting Scholar in History at Franklin & Marshall College.

“As the supposed ‘re-birth’ (for that is what the term means) of classical civilization, Renaissance scholars – especially Petrarch – saw the bit in the middle as a low point,” she told IFLScience.

Indeed, it’s Petrarch, an Italian poet from the 14th century, who usually gets the blame for the period’s dismissive moniker. But that’s unfair, actually: “In point of fact, Petrarch was talking about literature,” Marten noted, “but all these terms have become used to mark a supposed downturn in scientific, cultural and intellectual growth.”

And if the period looked shady to Renaissance scholars, it was positively Black 3.0 to the next bunch on the scene: the Enlightenment philosophers. As the name implies, these thinkers of the 17th and 18th centuries saw themselves as uniquely rational and sophisticated – and, crucially, more secular than ever before. The term “Dark Ages” started to take on more baggage: “Disdain about the medieval past was especially forthright amongst the critical and rationalist thinkers of the Enlightenment,” writes Robert Bartlett in his 2001 book Medieval Panorama. “For them the Middle Ages epitomized the barbaric, priest-ridden world they were attempting to transform.”

This, coupled with the comparative lack of historical sources from the time, deepened the period’s reputation as being backwards, superstitious, and stagnant. But is that really justified?

How “dark” were the “Dark Ages”, anyway?

To say that the early medieval period – which is what modern historians usually prefer to call the period – was a time of cultural stagnation is, at best, entirely too Euro-centric.

After all, the period often referred to as the “Dark Ages” spans roughly the fifth to 10th centuries – overlapping the Islamic Golden Age, for example, by a full 300 years. This was “a truly remarkable period in human history,” write Ahmed Renima, Habib Tiliouine, and Richard J. Estes in the book The State of Social Progress of Islamic Societies; “on[e] that encompasses the remarkable accomplishments made by Islamic scholars, humanists, and scientists in all areas of the arts and humanities, the physical and social sciences, medicine, astronomy, mathematics, finance, and Islamic and European monetary systems over a period of many centuries.”

Meanwhile, China was experiencing its own renaissance under the Tang Dynasty; the Maya civilization over in Mesoamerica was reaching a zenith, with advancements in writing, architecture, agriculture, government, religion, and science; even the Byzantine Empire, just southeast of Medieval Europe, went through a period we now refer to as its “golden age” at this time.

But even narrowing our view to Europe alone, the Dark Ages simply weren’t that dark, Marten told IFLScience. “There was lots happening,” she said, “even though much of the intellectual focus of the church-trained literate elite was on theology and rhetoric.”

There were at least two periods of significant cultural development in Western Europe throughout the period – they’re even sometimes known as the “Medieval renaissances”. Under the reign of Charlemagne, for instance, sweeping reforms saw the poor and middle classes educated for the first time, with “young men studying for the priesthood were also expected to know, rhetoric, dialectic, mathematics, music, and astronomy,” writes Michael Edward Stewart, an Honorary Research Fellow and Associate Lecturer in the School of Historical and Philosophical Inquiry at the University of Queensland, in a 2001 paper on the period.

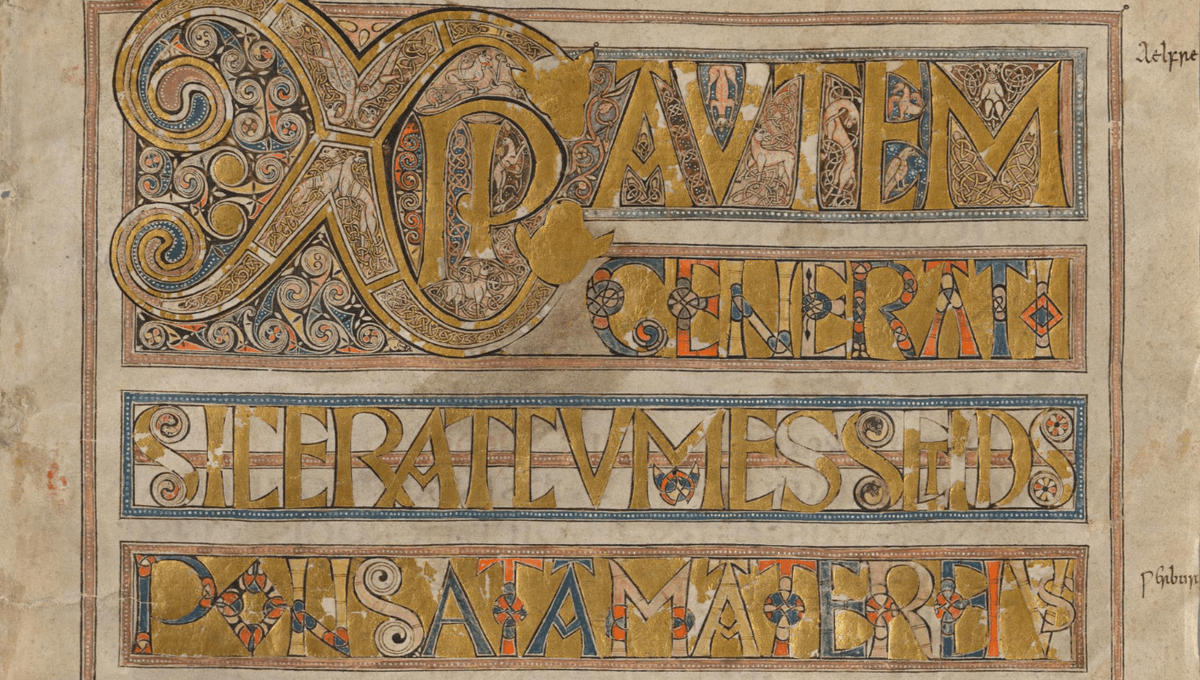

More than 50,000 books were produced in the ninth century alone – in fact, it was during this period that the handwriting style we read easiest today, humanist miniscule, originated; it was in short, Marten explained, “a flowering of intellectual thought… [it] helped to preserve many classical texts as well as generating new ways of thinking.”

The “dark” world

Far from being a cultural backwater, then, early medieval Europe was flourishing. International trade and relations were strong: “A burial such as Sutton Hoo… contains silverware from Byzantium and stunning gold jewelry containing garnets and lapis lazuli from India,” Marten told IFLScience.

Meanwhile, the ship technology of the Vikings made it from Scandinavia as far west as North America, South to the Azores, and East to at least Baghdad – potentially even further, Marten noted, with finds such as the “Helgö Buddha” hinting at trade links stretching as far as India. “I am fascinated by the cultural interaction,” Marten said. “The Vikings encountered over 50 different cultures in their travels.”

And in many ways, the so-called “Dark Ages” were strikingly modern. We’ve seen potentially non-binary graves from this era; concepts like gender and race were looser than in the following centuries; there are even accounts of queer and trans people existing quite happily during this period (heck, just read the account of Thor’s Wedding in the Poetic Edda if you’re looking for some feminist queer euphoria.)

“We have a great deal of stories that recount often the lives of figures who were assigned female at birth and basically live out their entire lives as men in all-male monastic communities,” noted University of California, Irvine, historian Roland Betancourt in the University of Chicago’s Big Brains podcast.

“There’s a lot of interesting evidence in the medieval world that demonstrates just how common same gender intimacies were and these various forms of queer relation were,” he explained. “John Boswell, who was a historian at Yale, very famously made the argument that Byzantium had a modern equivalent to same sex unions because there was this right known as the brother-making right, where two men could be joined a spiritual brotherhood, they could share the same bed, live together.”

Women, too, weren’t necessarily as bad off as you’re thinking. They could be educated just as much as the men in their lives – which, in fairness, wasn’t a lot in the Middle Ages, but still – and were known to work in trades, farming, or arts.

“There were many more opportunities [for women] than for a good few centuries following this period!” Marten told IFLScience. “Imagine being Gunfrid the Far-Travelled (c. 980 – 1019 CE) for example. She was Icelandic, gave birth to her son Snorri in North America, and later went on a pilgrimage to Rome.”

The Dark Ages – a deserved title?

So, what would life have been like for you or me in the Dark Ages? Well, frankly, that’s a hard question to answer: “just as today, that varies so much according to social class and geography,” Marten told IFLScience. Plus, she pointed out, even by the narrowest of definitions, we’re talking about a 500-year span of history – the equivalent of grouping today in the same era as the Pilgrim Fathers.

Of course, nobody’s saying the Dark Ages were some kind of utopia – in fact, they cover what is probably the worst time in human history to be alive, viz, 536 CE and the decades immediately afterwards (seriously). You’d likely have to put up with a plague or two – when don’t you? – and your chances were slim to bupkis on being able to read and write to any appreciable degree.

But as far as living in some period of uniquely stagnant arts, sciences, and culture goes – well, it turns out this supposedly “dark” age was a lot brighter than we’ve been taught.

Source Link: How "Dark" Were The Dark Ages, Really?