Fossils and ancient creatures sometimes tend to give researchers a headache just as much as they bring excitement to the team. One such item is part of a marine tapeworm that has been discovered trapped in amber – quite how a marine parasite ended up trapped in tree resin is leaving scientists scratching their heads.

The fossil is thought to be a species of the cestoda class, also known as tapeworms, that dates back to 99 million years ago. The tapeworm is trapped in mid-Cretaceous Kachin amber and was found in Myanmar. Cestoda is a widespread class that can even infect humans and is found in pretty much every ecosystem, including marine environments.

The order trypanorhyncha, to which our ancient trapped critter belongs, typically infect marine species of sharks and rays as larvae. Almost all living trypanorhyncha are endoparasites of sharks and rays. However, because of their complex life cycles that involve two hosts and soft bodies, they are only known in the fossil record from eggs found in shark coprolite.

“The fossil record of tapeworms is extremely sparse due to their soft tissues and endoparasitic habitats, which greatly hampers our understanding of their early evolution,” said Wang Bo, the study’s lead researcher in a statement. However, he added that his team had “reported the first body fossil of a tapeworm.”

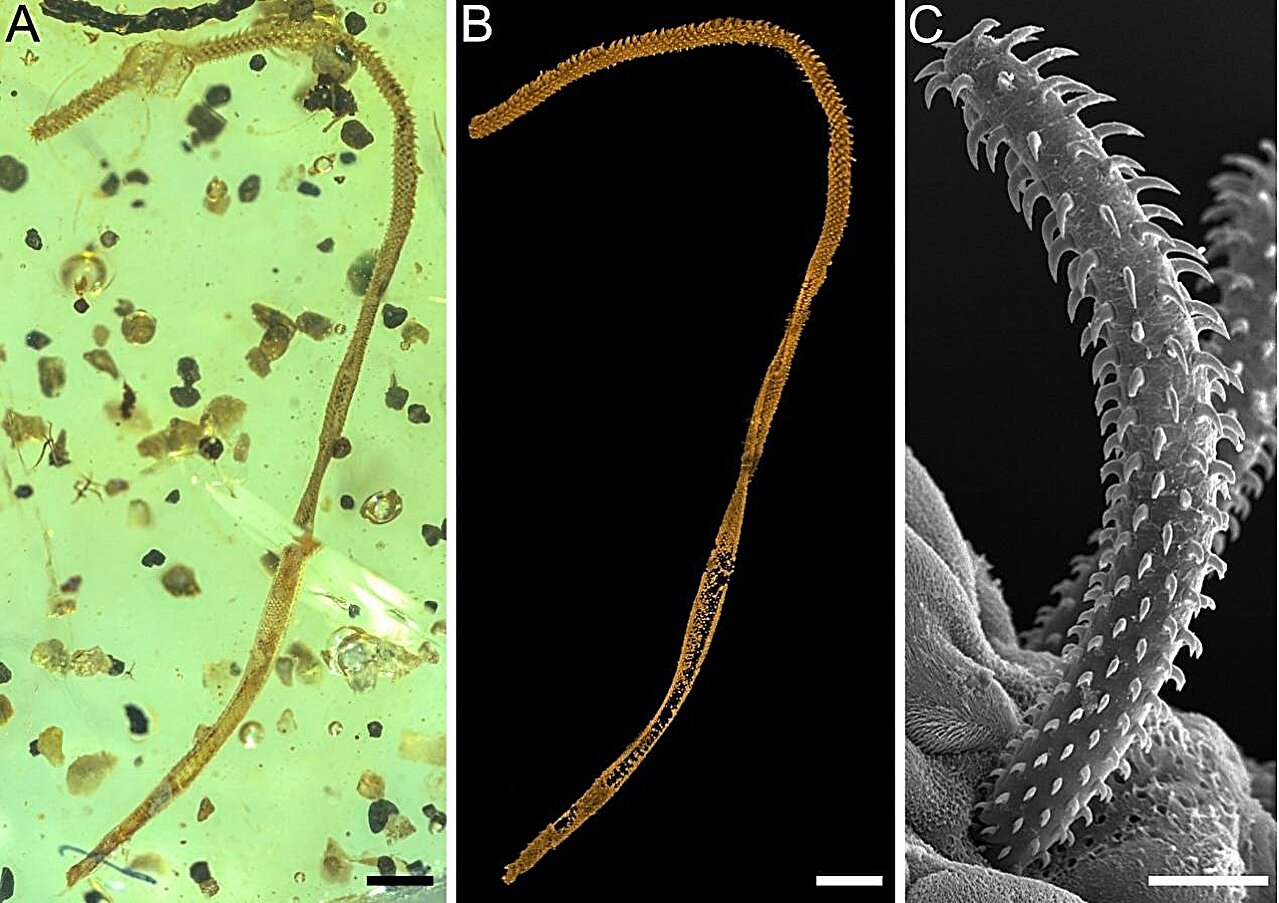

The amber has led to the exceptional preservation of the fossil, meaning it is likely the most convincing body fossil of flatworm ever found. The fossil, though incomplete, is long and slender and has incredible external and internal features along the tentacle, and rootless hollow hooks.

The fossil tapeworm tentacle compared to an extant species of trypanorhynch tapeworm.

Credit: NIGPAS

“This makes the current find the most convincing body fossil of a platyhelminth ever found,” said Luo Cihang, first author of the study and a PhD candidate from NIGPAS.

As well as the tapped endoparasite there are also fern trichomes and an insect nymph also trapped in the amber, further suggesting that the tapeworm was on land at the time of becoming entombed in the amber itself. The amber also contains sand grains, suggesting that it might have been a shore environment. The team also writes that the end of the fossil is fractured, suggesting it was ripped apart.

The authors suggest that the host for the parasite, the shark or ray, was stranded on a sandy shoreline after strong winds or tidal surges. The shark was then predated upon, and the parasite was pulled away from the intestine and stuck into nearby resin. They emphasize that this is a speculative idea, but highlight the importance of amber in preserving unexpected fossils.

“Our study further supports the hypothesis that the Kachin amber was probably deposited in a paralic paleoenvironment, and also highlights the importance of amber research in paleoparasitology,” finished Wang.

The paper is published in the journal Geology.

Source Link: How Did A “Bizarre” Fossil Marine Parasite Tentacle End Up Trapped In Tree Resin?