For a longer time than you’d expect – by some years – one of science’s most remarkable brains was kept inside a box labeled “Costa Cider” underneath a beer cooler in the corner of one man’s lab.

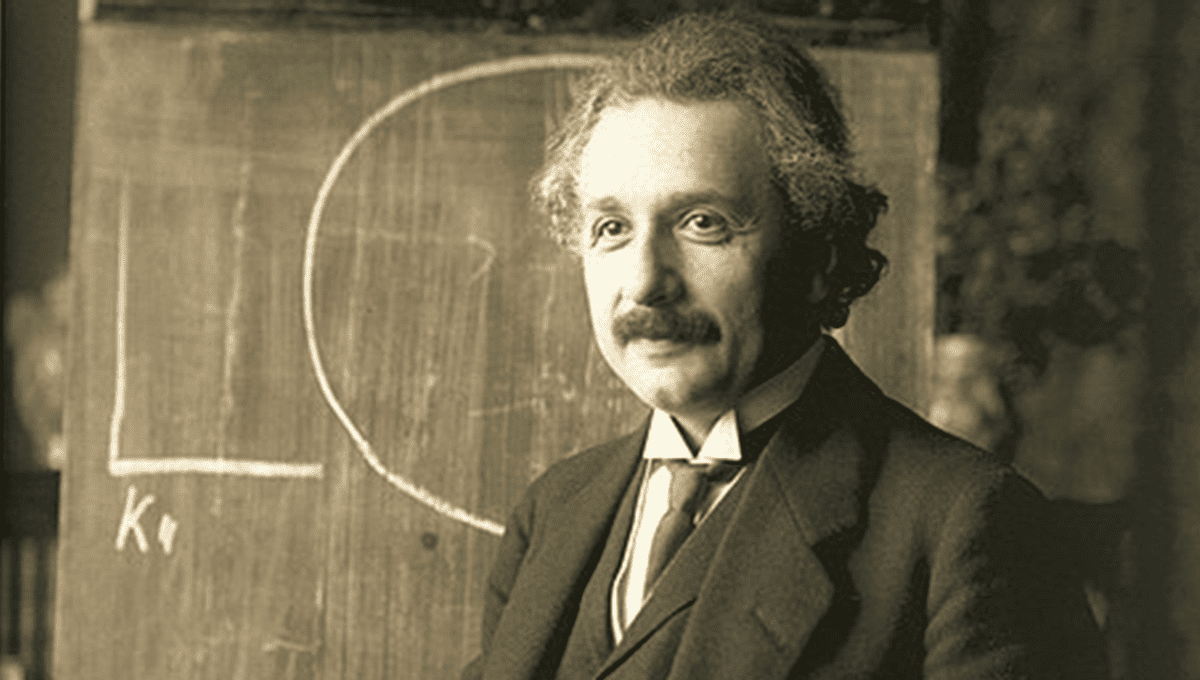

On April 17, 1955, aged 76, Albert Einstein was rushed to Princeton Hospital with internal bleeding caused by an abdominal aortic aneurysm that would lead to his death a day later. Refusing surgery, he reportedly told his family and medical team: “I want to go when I want. It is tasteless to prolong life artificially. I have done my share; it is time to go. I will do it elegantly.” He died on the morning of April 18, mumbling words in German that were heard by a nurse who, unfortunately, did not understand the language.

Einstein told his biographer: “I want to be cremated so people don’t come worship at my bones.” And so, after the autopsy, his body was cremated and his ashes scattered at a secret site, to prevent people from visiting his final resting place. However, after the cremation his family learned that the body had not been complete: during the autopsy, pathologist Dr Thomas Harvey had sawn open Einstein’s skull and removed the brain for study.

More controversial still, for a long time – 45 years, in fact – Harvey kept most of the brain in a jar.

Einstein’s son was, as you’d expect, not best pleased with his father’s brain being removed without permission. However, Harvey was able to convince him to give permission for the brain to be studied in order to figure out what made his mind so brilliant, and that he would publish his finding soon.

However, no scientific papers about Einstein’s brain were forthcoming. It wasn’t until 1978, when reporter Steven Levy investigated for the New Jersey Monthly and met Harvey, that it became clear what had happened to the brain.

Harvey had measured, weighed, photographed, and commissioned paintings of the brain. He had also overseen the division and storage of it, turning it into 240 blocks and 12 sets of 200 tissue sample slides at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia. He had given samples of the brain out for study, and at first, found little or no difference to non-Einstein brains. Or, at least, nothing that would show why Einstein was a lot smarter than your average non-Einstein.

He kept the samples safe and refused to let them be taken by the US army, who he claimed asked to see them. Soon after the publication of Levy’s article, Harvey was met with many requests for a piece of Einstein’s brain to study, including from the neuro-anatomist Marian Diamond from the University of California, Berkeley. Harvey mailed four sugar cube-sized samples of the brain to Diamond, inside a jar that used to house Kraft Miracle Whip mayonnaise. More samples were distributed to other scientists before Harvey turned the brain over to the University Medical Center at Princeton in 2004.

So, what did we learn from Einstein’s stolen brain? Not a whole lot, unfortunately, and what we have learned probably needs to be treated with a healthy dose of skepticism, or at least observed while murmuring “correlation does not equal causation” to yourself as a reminder.

“There’s a night-and-day difference between a living brain and a dead brain,” Anna Dhody, curator of the Mütter Institute, which now houses samples of Einstein’s brain, explained to the Smithsonian. “A living brain has infinite amounts of things you can study and learn. It is pretty finite in what you can learn from a dead brain.”

Diamond, having received the sample housed like it was mayo, published a paper in 1985 that found that Einstein’s brain had a higher percentage of glial cells, particularly in tissue thought to be involved in imagery and complex thinking, while another study in 1996 found Einstein’s neurons to be more tightly packed than those of controls.

Ultimately, though, there is only so much you can learn from this, given that we don’t know whether these differences were there from early on and helped with his thinking, or whether his brain developed in this way as a response to his complex work.

“You can’t take just one brain of someone who is different from everyone else – and we pretty much all are – and say, ‘Ah-ha! I have found the thing that makes T Hines a stamp collector!” psychologist Terence Hines told the BBC in 2015.

“If you have this notion that stamp collecting was caused by something different in the brain, and you looked at my brain and compared my brain to 100 other brains, you could find something different and say ‘Ah-ha! I have found the centre of stamp-collecting.’ And it’s bull.”

On Harvey’s part, taking Einstein’s brain did not do good things for his career, and he lost his job at Princeton hospital. As for his explanation for why he took it?

“I didn’t know anyone else wanted to take it,” he told the Press Gazette.

Source Link: How Einstein's Brain Ended Up In A Jar Of Kraft Miracle Whip Mayonnaise