A new study has uncovered how one subclass of marine mollusks, Heterobranchia, may have been able to survive and bounce back after a mass extinction event.

The end-Triassic mass extinction event happened around 201 million years ago and marked the beginning of the Jurassic period and the dominance of dinosaurs on Earth. Although less devastating than the earlier end-Permian mass extinction, known as the Great Dying, it’s safe to say that the event had an enormous impact on biodiversity both on land and in the sea.

However, scientists have now reported that certain sea snails may not only have survived the event, but actually went on to thrive in its aftermath.

The researchers constructed a database of information from published work on gastropod diversity and used it to map extinctions and the emergence of new genera between the late Triassic and early Jurassic periods. When they came to analyze the results, one subclass, Heterobranchia, stood out from the crowd.

Only around 11 percent of this genera were wiped out during the extinction event – this is compared with 56 percent of all gastropod genera and subgenera. Not only that, but the subsequent period also gave rise to a whole load of new heterobranch genera. So how did these particular snails manage to survive?

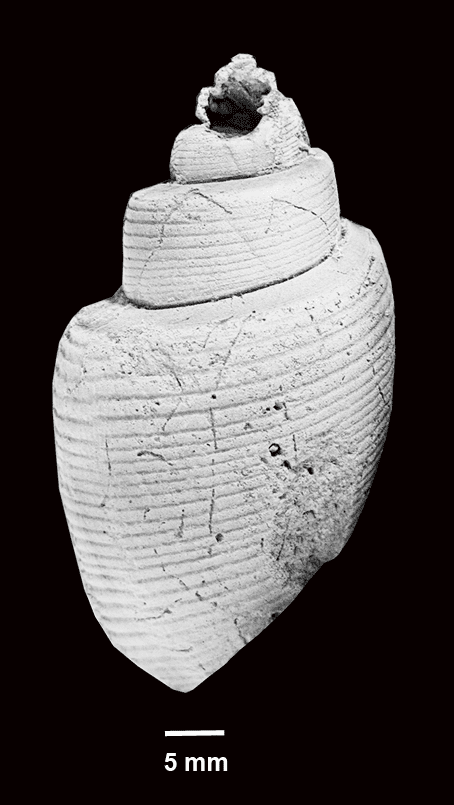

It’s difficult to know exactly how these ancient snails lived. Scientists can speculate based on the shape of their shells, what we think we know about the environment at the time, and by looking at modern descendants of these species.

Heterobranch shells provide clues to their survival. Image credit: Mariel Ferrari (CC-BY 4.0)

In the case of the heterobranchs, the new study offers three possible theories as to how they may have escaped extinction.

One theory relates to how the larvae of these snails feed. Heterobranch larvae eat plankton, but it’s possible that they were able to branch out (no pun intended) and consume non-living matter dissolved in the water. This would have put them at an advantage if the plankton themselves became extinct.

The second theory is that the heterobranchs may have been well adapted to living in warmer waters. As global warming at the end of the Triassic period made sea temperatures rise, heterobranchs may have been able to outcompete other, cold-loving species.

The final theory suggests that heterobranchs may have had a unique way of protecting their shells. They have a flexible mantle that covers part of the shell and may have helped safeguard them from the acidification of the oceans.

Whether by one or a combination of these factors, what we know is that these resilient snails managed to come through a mass extinction event comparatively unscathed – a mass extinction event which, at least for gastropods, was arguably as momentous as the Great Dying.

The study is published in the journal PLOS ONE.

Source Link: How Some Sea Snails Survived A Mass Extinction