For as long as humans have lived in close proximity to animals, there has been the ever-present risk of infectious agents making the jump from them to us. This process is known as spillover: when a pathogen, like a virus, crosses a species barrier to infect a new host.

It’s not a rare phenomenon; some estimates have suggested that over 60 percent of infectious diseases that have emerged in humans have animal origins. A list of these infections – called zoonotic diseases – reads like a who’s who of the most feared of human afflictions: Ebola, HIV, rabies, and bubonic plague, to name a few.

Recently, reports of spillover cases of bird flu in humans, including the tragic death of a young girl in Cambodia, have sparked fears of more such events. But what is the science underlying spillover, and how worried should we be?

How does spillover happen?

There are lots of factors that determine whether a particular disease will spill over into the human population.

To start with, you need to have enough of the infection circulating within the original reservoir host species. We’ve seen this with the current avian flu season, with huge numbers of birds infected with the H5N1 strain of the virus. More animals infected means more chance of humans coming into contact with them.

Diseases affecting species that humans are more likely to closely interact with post the biggest risk for spillover events. It makes sense that poultry farmers would have to take extra care to avoid bird flu. Another common culprit is bats, which are reservoirs for a number of human diseases including both Ebola and the related Marburg virus. There are lots of areas where humans live in close proximity to bat colonies, and bites can happen.

But, not every exposure to an animal pathogen results in a new human epidemic. There’s a reason why the occasional cases of H5N1 flu in humans have not translated into a major epidemic, as of yet.

As microbiologist Treana Mayer explains in an article for The Conversation: “While this new strain of bird flu can infect people in rare situations, it isn’t very good at doing so, because it is not able to bind to cells in human respiratory tracts very effectively. For now, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention thinks there is low risk to the general public.”

What types of diseases have been caused by spillover?

A 2021 review detailed the particular characteristics that make some pathogens more likely to make the jump.

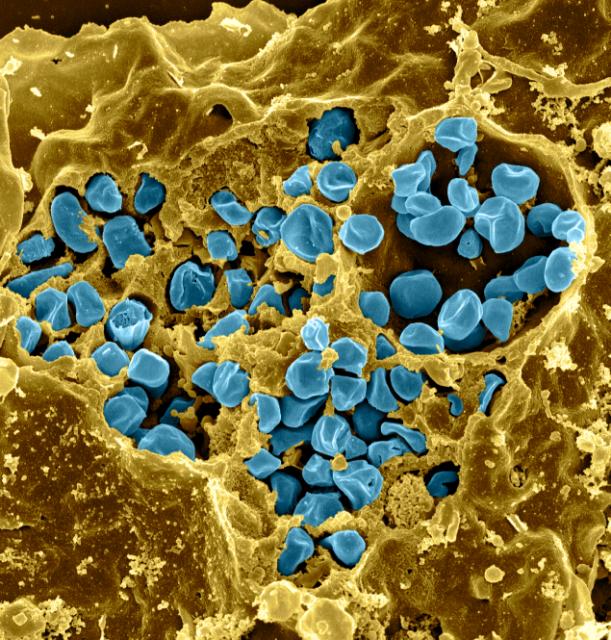

For viruses, those with an RNA-based genome are more likely to be able to adapt to a new host, because they have higher mutation rates. Those that are non-enveloped can linger in the environment for longer, so there’s more chance of these being picked up by an unwitting human.

With bacteria, antibiotic resistance is a growing concern, and not just in human medicine. Overuse of antimicrobial agents in livestock leads to the circulation of resistance genes among bacterial populations and increases the chances of these spreading to humans too, risking the development of infections with very few treatment options to combat them.

Certain pathogens are able to take advantage of quirks of the human immune system to successfully jump across the species barrier. For example, it’s been suggested that SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, was able to infect us so readily because the receptor it binds to, ACE2, shows such little diversity across human populations.

In some cases, pathogens make use of a middle man, another living vector that facilitates the leap from an animal reservoir to the new human host. Often, this will be an insect, such as a mosquito or tick. While not all vector-borne infections in humans are zoonotic in origin, some – like West Nile Virus and Lyme disease – most definitely are.

Once a pathogen has acquired the right combination of mutations to allow it to successfully infect a human, there is another hurdle – sustained human-to-human transmission. This may be more likely with pathogens that cause a chronic infection, hanging around for longer in the human body and picking up new mutations as they continue to replicate.

One example of a zoonotic disease that causes chronic infections in humans is a form of tuberculosis (TB) caused by Mycobacterium bovis, which typically infects cattle. When this spills over, it causes a disease very similar to the human TB that we’re all familiar with, which makes it difficult to spot – but it’s vital that clinicians do spot it. M. bovis is naturally resistant to the antibiotic pyrazinamide, so the usual first-line treatments for TB won’t work in these cases.

How worried should we be about spillover?

“Epidemiologists are projecting that the risk of spillover from wildlife into humans will increase in coming years,” writes Mayer, “in large part because of the destruction of nature and encroachment of humans into previously wild places.”

Human habitations are expanding further and further into wild places, bringing wild animals into closer contact than ever before with domestic and livestock animals. All of this creates the perfect conditions for spillover to occur – and, as we’ve all seen with SARS-CoV-2, an emerging infection can very quickly turn into a history-making pandemic, given the right confluence of circumstances.

Mayer calls for improved surveillance, as well as taking steps to try to prevent these events in the first place: “Active monitoring of wild animals, farm animals and humans will allow health officials to detect the first sign of spillover and help prevent a small viral splash from turning into a large outbreak. Moving forward, researchers and policymakers can take steps to prevent spillover events by preserving nature, keeping wildlife wild and separate from livestock and improving early detection of novel infections in people and animals.”

But the inescapable fact remains that the next big global threat to health will, likely as not, come from a non-human source.

Source Link: How “Spillover” Events Propel Animal Diseases Into Human Populations