Native speakers of German and Arabic have distinctly different brains, with increased connectivity in areas needed to handle the specific natures of their respective languages. The work not only explains why people may find it particularly difficult to learn a language with highly different structures from their native tongue, but it also boosts the credibility of controversial claims about how influential languages can be.

The Sapir-Whorf hypothesis holds that language structure shapes our worldview and how we think. Cynics argue that linguists would say that, as it makes them more important, but the idea is controversial even among specialists. Science fiction writers have seized on it, however. For example, the Native Tongue series imagines an effort to create a more equal and peaceful world by changing the language. An extreme version is presented in the film Arrival, where knowing an alien language makes it possible to see the future.

One doesn’t have to believe such fantasies to realize that strikingly different languages such as German and Arabic tax the brain in contrasting ways. A team at the Max Plank Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences report in NeuroImage the consequences of learning one from birth are visible in the way the brain is structured.

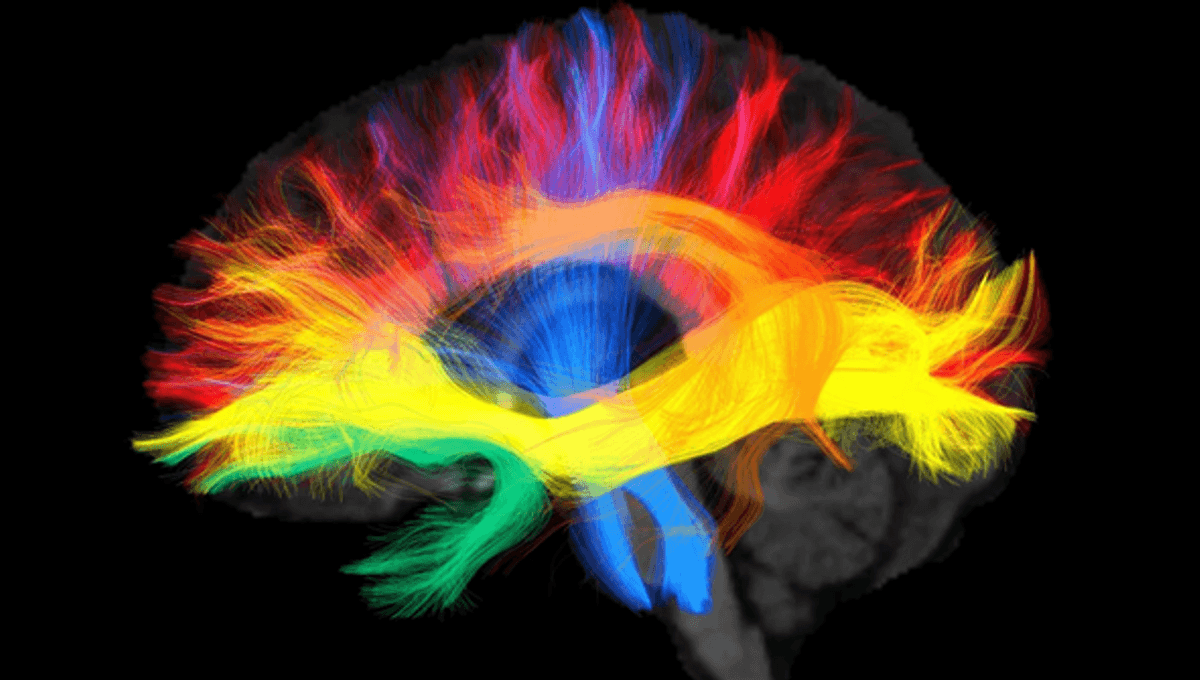

The authors used magnetic resonance tomography to study the brain connectivity of 47 native German speakers aged 19-34 and the same number of people who learned Arabic as their first language. Participants were highly educated, but all spoke only one language. To reduce confounding factors, all participants were right-handed.

“Arabic native speakers showed a stronger connectivity between the left and right hemispheres than German native speakers,” said senior author Dr Alfred Anwander in a statement. German speakers, on the other hand, have more connected left hemisphere language networks.

The authors attribute these observations to the demands Arabic’s combination of independently unpronounceable roots and word patterns, and German’s complex syntax, place on relevant brain regions. Like other Semitic languages, Arabic is read from right to left, which activates the brain’s right hemisphere equally with the left. Indo-European languages like German that run left to right are much more left-hemisphere focused.

For those who know their way around the brain, the German speakers’ stronger connectivity shows up in the intra-hemispheric frontal-parietal/-temporal language network. In addition to the greater connections between hemispheres, Arabic speakers benefited from extra wiring in the temporo-parietal lexical-semantic network.

“Brain connectivity is modulated by learning and the environment during childhood, which influences processing and cognitive reasoning in the adult brain,” Anwander added.

Previous studies have shown different areas of the brain are activated most heavily depending on the language being processed. Consequently, it is not surprising there is a long-term legacy, just as practicing a sport from an early age builds the muscles required. Nevertheless, the effect has not been shown before with a sample of this size.

These extra connections should make it easier for speakers of a particular language to learn others that, while not necessarily similar, make heavy use of the same brain regions. They may also assist in learning other skills that similarly draw on the areas developed by early exposure to the language in question.

The team are interested in finding out to what extent learning a language later in life can replicate the influence on the brain of starting young. They will repeatedly observe the brain connectivity of Arabic immigrants as they start the process of learning German. Some previous research indicates that languages learned in adulthood, and possibly even second languages learned as a child, are processed in different parts of the brain from the native language system.

The study is published in NeuroImage (open access).

Source Link: How Your Native Language Changes The Structure Of Your Brain