For the first time, researchers have found evidence that people were using red ochre in West Africa during the Middle Stone Age. Dated to between 30,000 and 40,000 years ago, the rust-colored artifacts appear to have been crushed into powder and used as “crayons”.

According to the study authors, the presence or absence of ochre at an archaeological site serves as a proxy for the cultural and behavioral complexity of ancient humans. A natural pigment containing iron oxide and clay, the reddish material was used by prehistoric tribes for a variety of ingenious purposes, including as a sunscreen and loading agent for glue-like adhesives.

Ochre was also the material of choice for the world’s earliest artists, who used the earthy pigment to create cave paintings and decorate shells, bones, and other artifacts. Many prehistoric rituals are also thought to have involved the use of ochre as a body paint, all of which suggests that the substance played an integral role in the development of abstract human thought and symbolic behavior.

To date, most of the oldest evidence for ochre use comes from southern, eastern, and northern Africa, where the rouge hue became a fixture in the archaeological record around 160,000 years ago. Last month, researchers announced the discovery of the world’s oldest ochre mine in South Africa, which is thought to be around 48,000 years old.

In West Africa, however, the picture is somewhat different. Prior to the new study, there had been no major research conducted on Middle Stone Age ochre remains in the region, making it difficult to reconstruct the pace of behavioral evolution in this part of Africa.

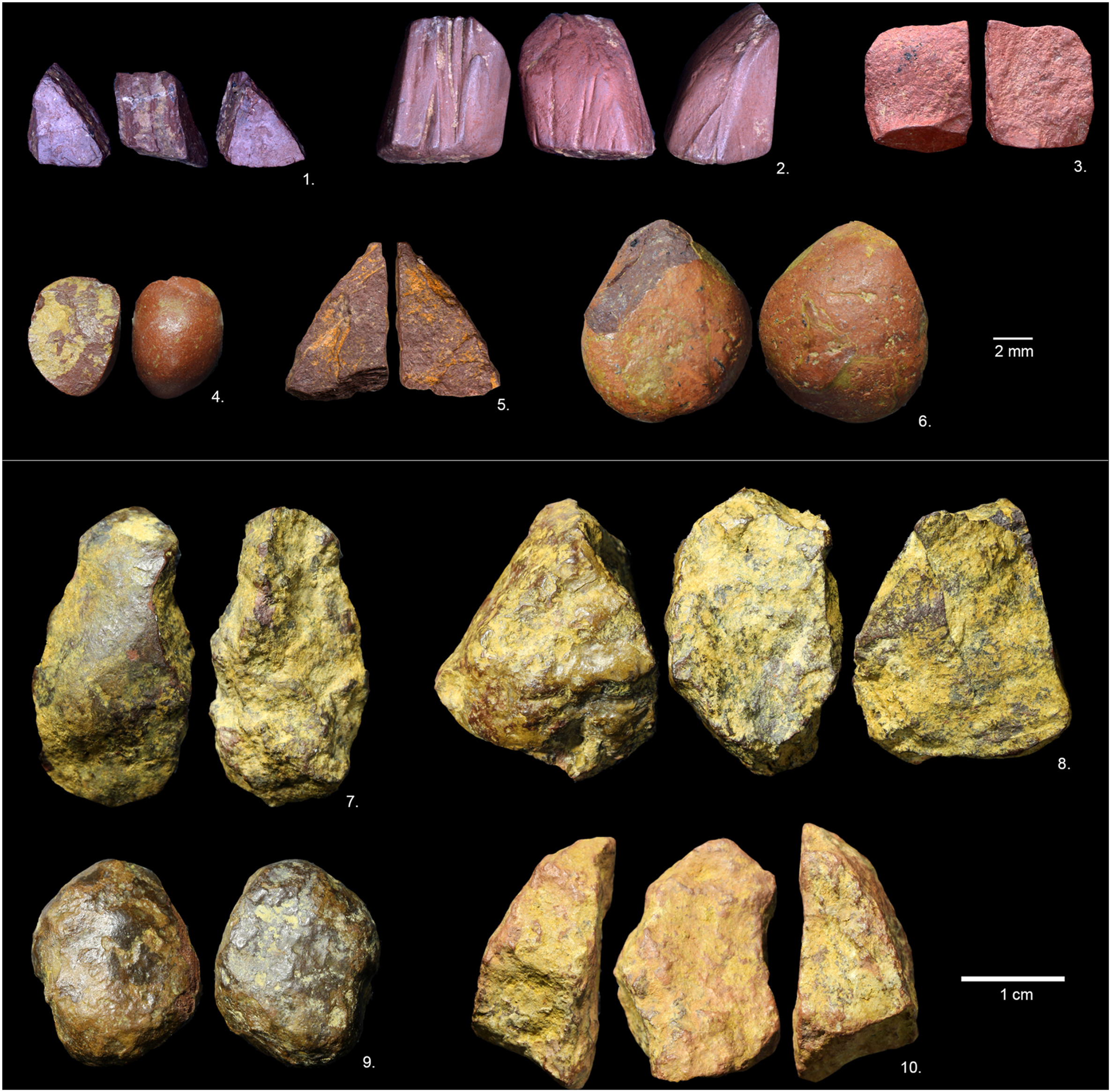

Adding some much-needed color to this archaeological black hole, the study authors report the discovery of 46 ochre pieces from the Toumboura III site in Senegal. Based on the angles and strike marks left on these fragments, the researchers conclude that many of them appear to have been ground into powders, although exactly what this red dust was used for remains a mystery.

A selection of ochre pieces found at Toumboura III.

After analyzing the various iron-rich raw materials found at the site, the authors conclude that these powders probably weren’t used as sun protection, as this requires pure iron oxides while the assemblage at Toumboura III contains variable iron content.

In addition to these crushed pigments, the site also yielded four ochre sticks that don’t appear to have been made into powder. Noting that two of these sticks display a “grinded face and a battered end”, the study authors suggest that “they may have served as ochre crayons and may also have a function of pigment.”

Overall, it’s impossible to say exactly what the prehistoric inhabitants of Toumboura III got up to with their colorful clay, although the very fact that ochre has been discovered here transforms our understanding of human behavior in the region 35,000 years ago.

“These remains could represent the earliest known evidence of ochre exploitation in Senegal,” write the study authors. “They potentially open new perspectives on symbolic behaviours in the Middle Stone Age of West Africa,” they add.

The study is published in the Journal of Archaeological Science.

Source Link: Humans Have Been Using Red Ochre In West Africa For 35,000 Years