The discovery that birds are dinosaurs shook up how we structure the tree of life, and led to a lot of jokes about chicken nuggets. However, it has made some people wonder why they’re all so diminished in size compared to the giants of the past. There were plenty of small dinosaurs pre-asteroid, but the clade is famous for being big, which isn’t how we think of modern birds.

If you’re looking for a single, simple explanation for the difference, however, you’re unlikely to get it.

IFLScience asked paleontologists Dr Melanie During of Uppsala University and Dr Jingmai O’Connor of the Field Museum of Natural History the question. Both have previously told IFLScience they think we are still living in the age of dinosaurs thanks to their diversity, and both think there are several factors behind their lack of giant size. However, they don’t entirely agree on what those factors are, leaving a wide range to choose from.

Bird vs dinosaur size

Some modern birds are impressively large if you measure by wingspan. Some albatrosses stretch 3.5 meters (12 feet) wingtip to wingtip. However, most of that size is feathers. The heaviest flying birds weigh 20 kilograms (44 pounds).

However, if we’re thinking about flight, birds should be compared to non-dinosaur contemporaries of T.rex such as pterosaurs, and that’s a discussion for another day.

Today, the largest birds not appearing on Sesame Street are ostriches, weighing up to 145 kg (320 lbs),

By comparison, we think T-rex weighed 8-10 tons, heavier than elephants. Sauropods, of course, got even bigger, but they’re more distant relatives of modern birds than theropods like Tyrannosaurs.

Early tyrannosauroids were feathered, so this was not an impediment. Tyrannosauroids reduced (but likely did not lose) their feathers when they got very large (think elephants, they are still covered in hair, it’s just sparse).

Dr Jingmai O’Connor

We know birds can get bigger than this. Seven hundred years ago, moa reaching 3.6 meters (12 feet) tall and weighing 230 kg (500 lbs) roamed New Zealand/Aotearoa. Not much earlier, Madagascar’s elephant bird included Aepyornis maximus, which laid the largest eggs we know of. While not exceeding 3 meters (10 feet) tall, they weighed somewhere between 275 kg and 1,000 kg (600-2,200 pounds), depending on which estimates you believe. Australia’s largest “ducks of doom” (Dromornis stirtoni) were similar in size.

Why Not Bigger?

All of these, like a great many large mammals, went extinct shortly after humans reached their homelands. So one obvious explanation is us. However, while humans can be blamed for a lot of things, including eliminating the largest birds, there’s still a factor of at least 10 between an elephant bird and a T.rex, so that’s not it.

Perhaps the blame lies not with humans per se, but with mammals in general. Did the furry grab the big niche before the feathered could get there in the asteroid’s aftermath?

O’Connor told IFLScience we can rule that one out. “Birds actually beat mammals to the large carnivore niche. Phorusrhacids, aka terror birds, were around roughly 62-2 million years ago and had skulls nearly a meter long.” As far as we know, terror birds never got quite as big as the largest elephant birds, but as carnivores, they may be T.rex’s closest avian comparison.

Big animals are usually more vulnerable when conditions change, so mass extinctions often leave small survivors, whose descendants take some time to get big. However, if terror birds appeared between 4 and 23 million years after the asteroid, depending on estimates, it’s hard to argue that the following 43-62 million years haven’t been long enough for birds to really break the size barrier.

During pointed out to IFLScience, we can’t be certain that there haven’t been some giant birds at times.

Birds have hollow bones, as did other dinosaurs. During told IFLScience this is part of their respiratory system, which is fundamentally different from that of mammals. This offers many advantages when alive, and During says this hollowness helped sauropods grow to their tremendous size, but it also hinders fossilization, affecting what we know of avian evolution.

Elephant birds and moa were both examples of “island gigantism”, where some species take advantage of limited competition to grow far beyond their continental size. Many islands have long since been lost beneath the oceans, taking any records of their fauna with them. Others may have lacked good conditions for fossilization at crucial points in time. Indeed, During noted, “There are not many Paleocene rocks to even look for bird bones.” When we find them, they get less attention from fossil hunters than those expected to host big, exciting dinosaur bones.

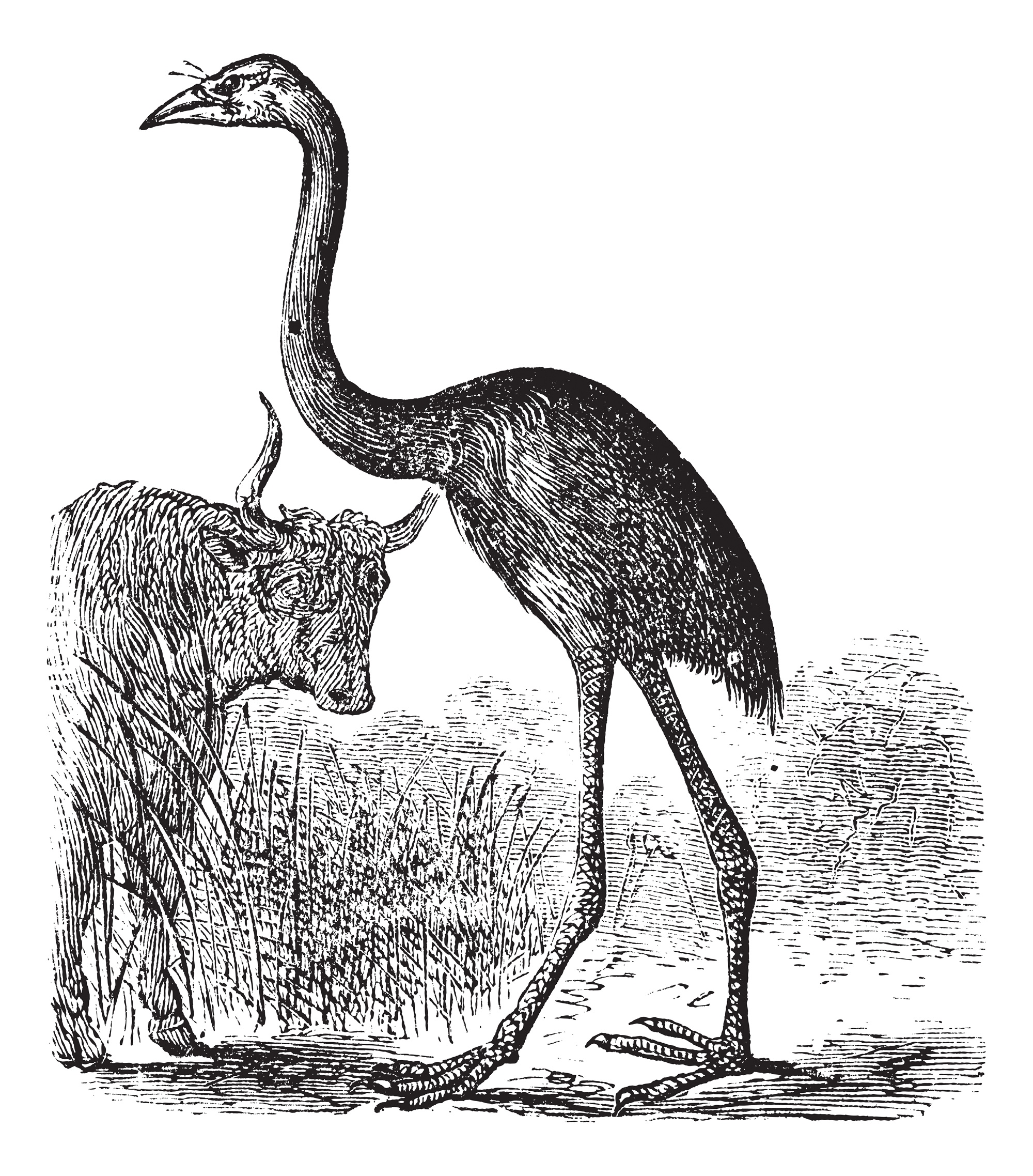

Moa were big, but not that big.

Image credit: Morphart Creation/Shutterstock.com

Moreover, we have little idea what creatures inhabited Antarctica in the tens of millions of years between the end of the Cretaceous and its permanent glaciation. That’s particularly relevant in the light of During’s argument that big animals are at risk of overheating, and feathers make this worse. On that basis, if any birds were going to get really big, they needed to live either in polar regions or dump their feathers. If members of that line had sacrificed their feathers for size, “Would we even call them birds?” she asked.

O’Connor doubts feathers were the problem. “Early tyrannosauroids were feathered, so this was not an impediment. Tyrannosauroids reduced (but likely did not lose) their feathers when they got very large (think elephants, they are still covered in hair, it’s just sparse),” she told IFLScience.

“Most likely, flightless birds never got as big as T. rex for reasons inherent to their physiology. Birds in general grow fast, have very high metabolisms, and have delicate skeletons,” O’Connor said. “Being big and having a very high metabolism would also be very costly. Additionally, with no large herbivores, there is no evolutionary pressure to grow to gigantic sizes.”

However, During isn’t convinced that too much should be made of the lack of large herbivores. “It’s naïve to think the T. rex preyed on the really large sauropods,” she told IFLScience. “They might go after the young, but not adults.” Consequently, she doesn’t think the Mesozoic had some growth-enhancing feature, such as more food, that caused larger plant-eaters, leading in turn to bigger predators.

During also questioned the basis for the question, noting that while birds are dinosaurs, “They are not derived from the T.rex. They broke off that line in the Jurassic.”

O’Connor summed up her position: “I think the simple answer is that there was no evolutionary advantage to being as big as a T. rex for neornithine birds.”

Source Link: If Birds Are Dinosaurs, Why Are None As Big As T. Rexes?