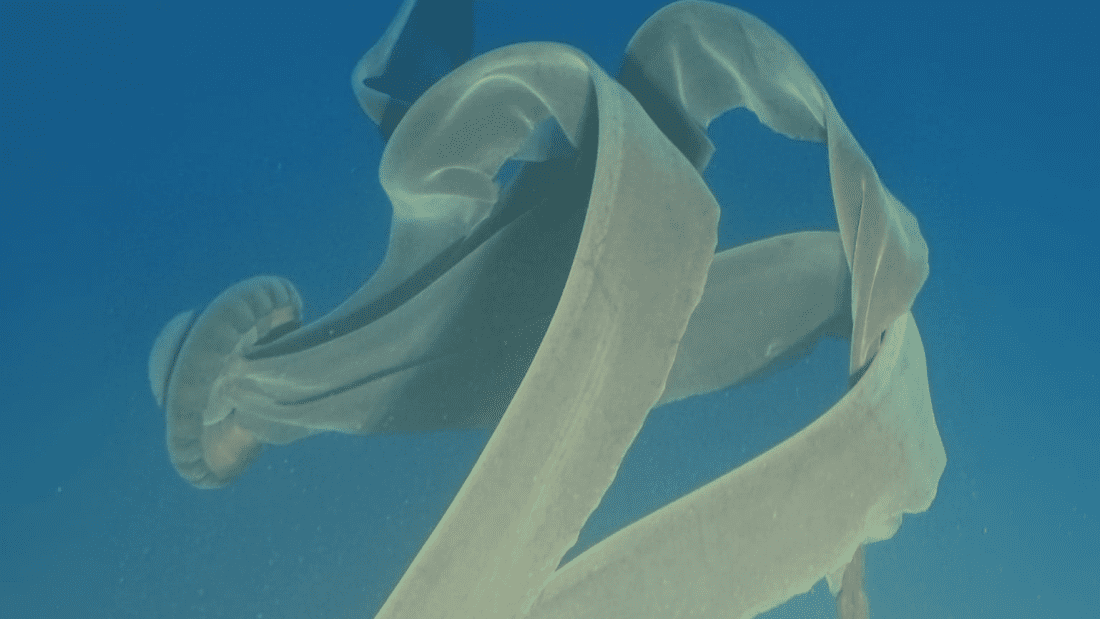

A mystery from the deep just got a little bit less mysterious thanks to the first scientific paper to arise from the Viking Expedition Team. While drifting through Antarctic waters, a guest snapped a picture of Stygiomedusa gigantea, commonly known as the giant phantom jellyfish.

Looking a bit like an errant piece of Halloween toilet roll teepeeing through the deep, these beasts really live up to their name, stretching to a gargantuan 10 meters (30 feet) in length, and yet since they were named back in 1910 only 126 encounters with S. gigantea have been recorded. To find out more about a day in the life of the Viking Expedition Team, we spoke to Chief Scientist of Viking Octantis Dr Daniel Moore about his research and advice for aspiring ocean explorers.

What was it like seeing the giant phantom jellyfish, Stygiomedusa gigantea?

The first time I saw the giant phantom jellyfish was on the back of a camera when a guest, who had been on a submersible dive that morning, wanted to show me a photo of a strange jellyfish they had seen. I instantly recognised it for what it was and, given the rarity of sightings, was flooded with excitement.

Only 126 encounters with the giant phantom jellyfish have been recorded since the species was first described in 1910. Image credit: Antony Gilbert, Viking

That moment was incredibly special as it was a moment of knowing that we were conducting real exploration with so much potential for new discovery. I knew that our submersibles were going to be exciting platforms for science, but I hadn’t expected results so early into the first Antarctic season for Viking. As a passionate advocate for citizen science, I was almost equally excited that these observations had been made by one of our guests (as have nearly all observations since).

Do you have any similarly memorable observations from your fieldwork?

I’ve been fortunate in my career so far to conduct science operations in many remote locations and on some rare species. Seeing the giant phantom jellyfish reminded me a great deal of where my career started – as a deep-sea biologist studying strange shark species, found a mile below the surface of our ocean. These sharks are typically dark in colour, have large green eyes and incredible adaptations – such as being bioluminescent or venomous. Being able to see these animals that so few people have the opportunity to witness is a real privilege.

As jellies go, the giant phantom is pretty leggy, but those long bits are actually “oral arms”. Image credit: Mark Niesink

What are you working on next?

As we finish off our time in the Southern Hemisphere, we’ll relocate the Viking Polaris to the Great Lakes region. This transit north is a great opportunity to write up our data from Antarctica and understand more fully what we have discovered. The project I am most excited about is one that again, comes from our submersibles and where all of our data comes from our incredible guests onboard.

During this past Antarctic season, we have been asking our guests to take photographs of the sea floor wherever they dive. These are areas of the sea floor that no human being has ever seen before. We are now analysing these photographs to understand differences in diversity and community structure between different seabed habitats around the Antarctic peninsula. I love that all of this data comes from Viking guests – they are each making a valuable contribution to our understanding of these amazing habitats that are 150-300 meters [492-984 feet] below the surface. I’d call that extreme citizen science!

One of the submersibles used by the Viking Expedition Team. Image courtesy of Viking

What advice would you give to someone wanting to follow in your footsteps?

I get asked this question a lot and it can be a tough one to answer as there is no set path to becoming a marine biologist on expeditions. You’ll need a degree and likely a master’s degree in Marine Biology but that is only the start. It is a competitive field, so volunteering and gaining field experience is vital.

Beyond that, having a passion for the subject and keeping that alive as you progress is really key. I find the best way to do this is to try and channel that curiosity we all have as children and ask yourself questions about the natural world. Why does an animal do that? How does an animal find its food or avoid predators?

It’s also important to take moments to just enjoy the wonder of nature and feel inspired by the things we see and the places we visit on expedition.

Source Link: IFLScience Meets: Dr Daniel Moore On Giant Phantom Jellies And Venomous Deep Sea Sharks