In the history of medicine, there is one story that is a fantastic example of how observation and experimentation can lead to significant changes and discoveries. The same story, however, is also an extreme example of how some scientific ideas can nevertheless be dismissed in favor of tradition.

During the 1840s, at the Vienna General Hospital’s maternity clinic, the largest in the world at the time, a strange and perplexing phenomenon was taking place. The maternity clinic was divided into two wards: if you were a pregnant woman admitted to Ward One, there was a 29 percent chance that you would die during your stay, but if you were admitted to Ward Two, you only had a 3 percent chance of dying. So, what was going on here?

During the 18th and 19th centuries, childbed fever, or puerperal fever, was an infection contracted during or after childbirth and was a common cause of death in hospitals with maternity wards. The disease tended to affect women within the first three days after giving birth and had a rapid progression, leading to abdominal pain, fever, debility, and, more often than not, death.

For contemporary physicians, the disease was a mystery. For one thing, germ theory of disease had not been established, so people had no concept that bacteria could be a cause of infection. This made it difficult to comprehend how epidemic childbed fever was being spread to different patients.

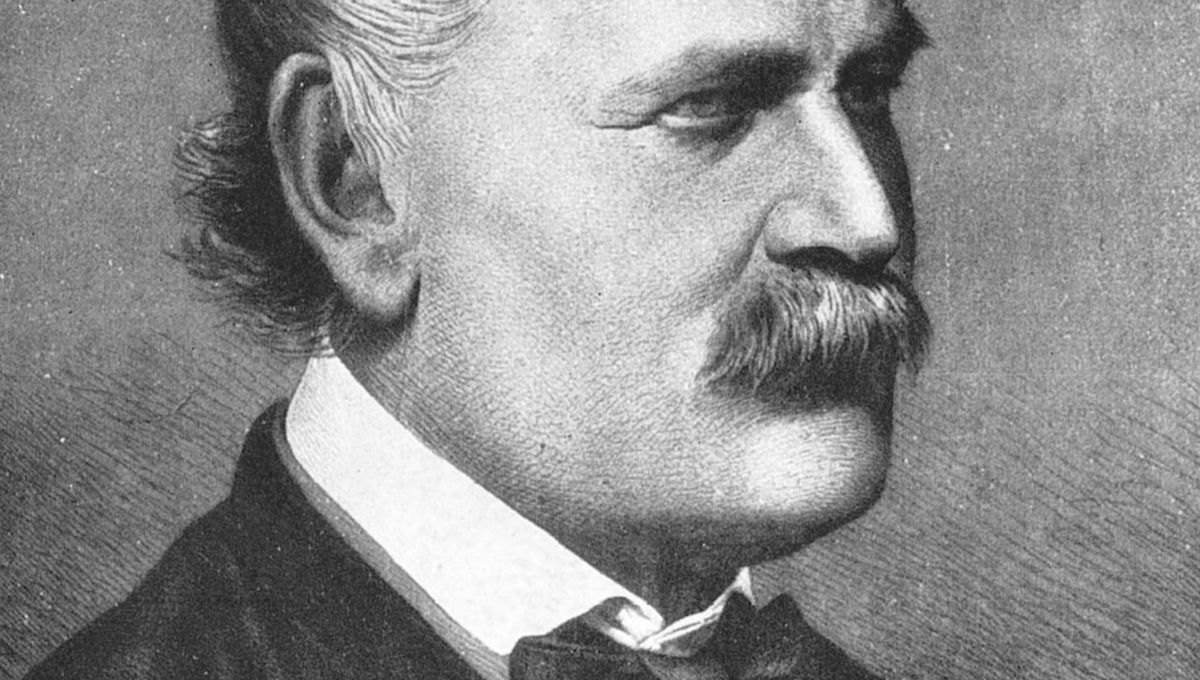

Enter Ignaz Semmelweis, an assistant physician at the Vienna General Hospital. Semmelweis observed the strange, uneven number of deaths occurring between Wards One and Two and concluded that the only difference was that the former was managed by medical students and the latter by trainee midwives. In order to test his observations, Semmelweis allegedly had the two wards swap staff and he found that, much like angels of death, the high mortality rates followed the medical students.

Another piece of the puzzle came when Jakob Kolletschka, a professor of forensic medicine, died after a student accidentally cut his finger during an autopsy. Semmelweis noted that the sepsis that had killed Kolletschka left similar pathological signs in the body to the women who died of childbed fever.

“Day and night I was haunted by the image of Kolletschka’s disease”, Semmelweis recorded, “and was forced to recognize, ever more decisively, that the disease from which Kolletschka died was identical to that from which so many maternity patients died.”

Semmelweis believed that, as the medical students would go straight from performing autopsies, often with the same clothes and soiled instruments, they were somehow passing infectious matter to the pregnant women with their hands. In May 1847, Semmelweis institutionalized a policy where all staff had to wash their hands with chlorinated water before attending to their patients. The mortality rates plummeted in both wards.

Yet, while it would be tempting to regard this as a prime example of the scientific method in practice, the story is not that straightforward. Unfortunately, Semmelweis’s ideas were challenged by his colleagues who believed the deaths were caused by miasma – bad air that was entering the wards through the ventilation system. Out of frustration, Semmelweis resigned his position in Vienna and moved to Budapest where he became the head of obstetrics at St Rochus Hospital. Once in his post, Semmelweis taught his new colleagues the virtues of washing hands and instruments, which had the same outcome for mortality rates.

He later published a book in 1861 explaining his views on childbed fever, but it was not well received. Semmelweis soon fell into obscurity and became embittered against the medical community which doubted him. He became increasingly unstable and was eventually forced into an asylum where he lingered until he died at the age of 47.

Semmelweis’s story is an instructive example of how some scientific ideas and discoveries can still be passed over due to established traditions. However, Semmelweis is also an active player in this narrative of rejection. He was known to be arrogant and difficult, often being openly insulting to his colleagues and opponents.

Nevertheless, his work eventually received greater appreciation after Robert Koch and Louis Pasteur produced their research into bacteria as causal agents of disease. Though even then, the much-acclaimed “bacteriological revolution“ took some time to convince everyone.

To read more fascinating stories, check out our free Common Medical Myths And Misunderstandings eBook.

All “explainer” articles are confirmed by fact checkers to be correct at time of publishing. Text, images, and links may be edited, removed, or added to at a later date to keep information current.

Source Link: Ignaz Semmelweis And The Controversial Crusade For Washing Hands