Can spiders still spin webs in microgravity? Fortunately, we know the answer thanks to two arachnids, Arabella and Anita, who were blasted off to space in 1973.

The idea for the “arachnaut” experiment originally came from a 17-year-old high school student in Massachusetts called Judith Miles. Presumably by coincidence, she suggested the idea in 1972, the same year David Bowie released the album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.

Her proposal was put forward as part of a NASA project that allowed students to suggest experiments onboard Skylab, the first US space station, which briefly operated a few missions between May 1973 and February 1974.

NASA loved the idea, so it was selected to be part of Skylab 3, the second crewed mission of the mini space station. Two female European garden spiders, also known as cross spiders, were put into two small plastic bottles and launched into low-Earth orbit on July 28, 1973. Once everything was in place, Arabella was coaxed into a specially designed tank and left to do her thing.

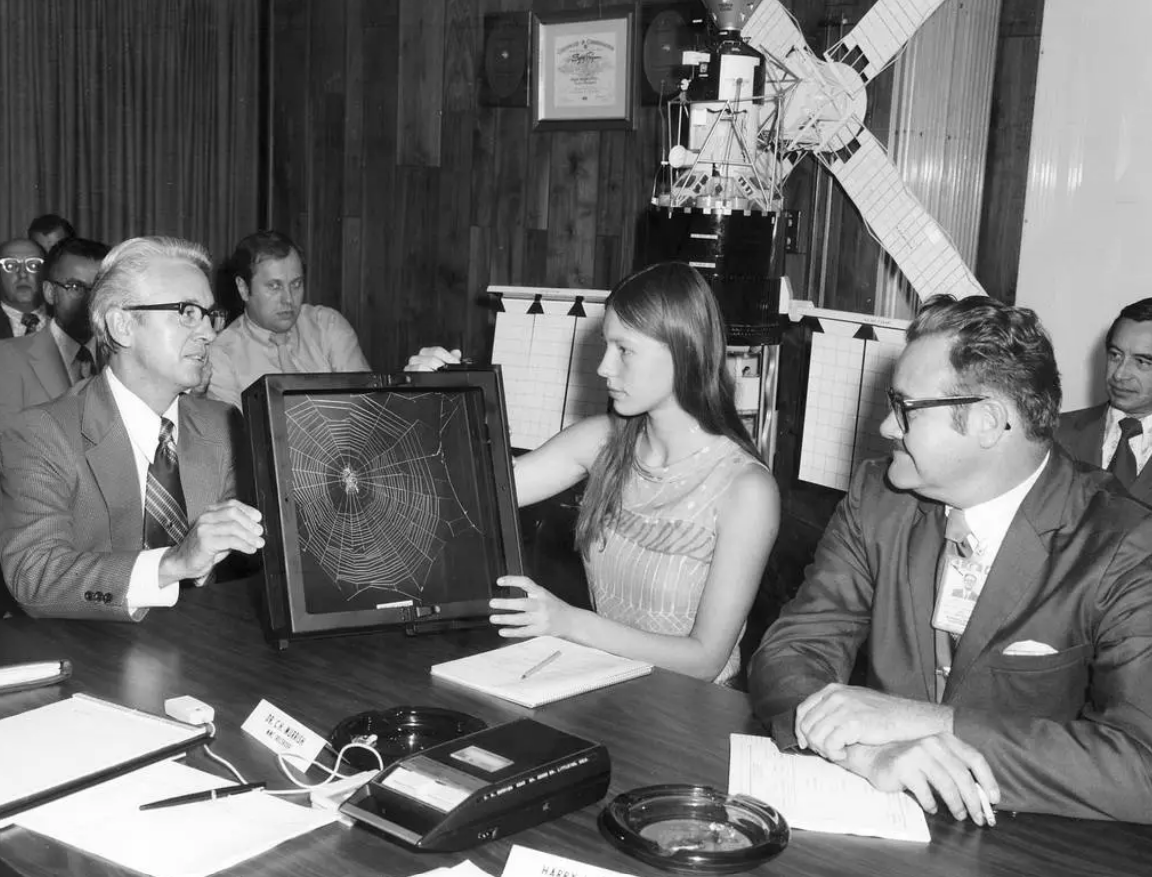

High school student Judith Miles discusses her proposed Skylab experiment with Keith Demorest and Henry Floyd, both of Marshall Space Flight Center, in 1972.

Image credit: NASA

According to the results, Arabella initially struggled to adapt to the new conditions, creating a web that was “rudimentary” at best. However, by day two, she started to form complete webs. The team was keen to see how things developed, so they extended the experiment and introduced Anita mid-mission.

In sum, the pair took some time to get used to the strange surroundings, but they quickly learnt to spin webs just as well as they did back home on planet Earth, albeit with finer silk.

Although spiders were the subject of the study, the findings were intended to solve broader questions about how near-microgravity impacts the central nervous system of animals, including humans.

NASA explains: “The geometrical structure of the web of an orb-weaving spider provides a good measure of the condition of its central nervous system.”

“Since the spider senses its own weight to determine the required thickness of web material and uses both the wind and gravity to initiate construction of its web, the lack of gravitational force in Skylab would provide a new and different stimulus to the spider’s behavioral response,” it added.

In other words, the ability to spin webs could provide insights into how our motor and central nervous systems might react to alien conditions.

Sadly, neither spider lived to tell the tale. Arabella and Anita both died on the space station, most likely as a result of dehydration. RIP. Gone, but not forgotten.

Since the 1970s, several experiments have sent spiders into low-Earth orbit in an effort to unravel how life adapts to space. In recent years, scientists at the University of Basel studied the behavior of Trichonephila clavipes spiders aboard the International Space Station (ISS), focusing on the symmetry of the webs they spun.

On Earth, spiders typically build asymmetrical webs, with the center positioned closer to the top. This puts them in a better spot to scuttle downwards quickly, using gravity, to snare prey that hits the lower part of the web.

Fascinatingly, the webs built in near-zero gravity on the ISS were more symmetrical than those spun on Earth, with the center closer to the middle. Despite having no evolutionary experience with space, the spiders adapted their web-building behavior remarkably quickly.

Source Link: In 1973, NASA Sent Two Spiders Into Space To See If They Can Spin Webs – And They Learnt A Lot