If you look in the right places, you may encounter the claim that there is only one, or two depending on who is speaking, places on Earth where you can walk directly on the mantle. Is this true, what does it even mean, and if it’s real, how did it happen?

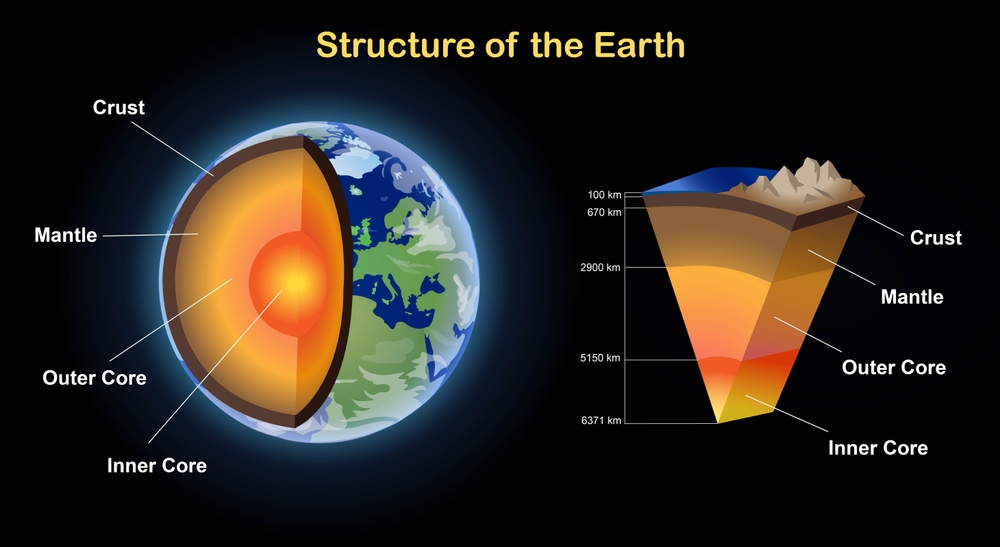

Any model of the Earth (well, any scientific one) will show the crust wrapped around the mantle, which in turn surrounds the outer and then inner core. That seems the natural order of things, and therefore if we want to examine the mantle, we need to drill at least a kilometer down.

In a sense, the mantle sometimes comes to us; volcanoes that sit above hot spots are driven by mantle plumes of hot material that punches its way through the crust and spews out as lava. However, if setting foot on the volcanic rocks that form when the lava cools was all it took to walk on the mantle, then you could do it in hundreds of places, not just one or two.

The layers that form Earth.

Image credit: Zaporizhzhia vector/Shutterstock.com

The Island On The Ridge

Bigger claims are made for Australia’s subantarctic Macquarie Island. Here, you can walk not just on former liquid from the mantle that cooled to become another piece of the crust, but on a swathe of the mantle pushed upwards intact.

In 1997, Macquarie Island was listed as a World Heritage site. The listing described the island as: “The only place on earth where tectonic forces have brought oceanic mantle-derived rock to the surface within the context of a currently active plate boundary.”

Macquarie was listed for many reasons, some of them relating to its concentration of penguins and albatrosses, but mostly for the unique opportunity to study processes that normally occur deep beneath the ocean.

Most visitors to Macquarie Island come for the seals and penguins, but the rocks they lie or stand on are arguably more remarkable.

Image credit: Charles Bergman/Shutterstock.com

Macquarie Island is quite small – twice the size of Manhattan – and if you think it seems unlikely the mantle would make its way through the crust here and almost nowhere else, you’re right. Mapping of the sea floor reveals that Macquarie Island sits on a 1,600-kilometer (900-mile) ridge, which runs from near New Zealand down towards Antarctica.

The whole ridge represents a thin strip of mostly mantle material, which has been squeezed upwards between the Indo-Australian and Pacific plates. However, while this ridge is much higher than the plates on either side, let alone the trenches that immediately border it, most of it is still far beneath the ocean. No walking there. Only on the island that gives the ridge its name, and a few smaller islands nearby, has the mantle been squeezed up so far that it pokes above sea level.

It’s possible that at some other plate boundaries there are similar ridges of mantle material we have yet to discover because they never get high enough to be exposed to the open air.

A Piece Of Middle Earth

Macquarie Island is very difficult to get to if you’re not a research scientist. Much of the island’s unique native wildlife was pushed to the edge of extinction by cats, rats, and rabbits introduced when the island was used for hunting seals and penguins. An eradication campaign has proved an enormous success, leading to many species rebounding, but it was an expensive one. To limit the risk of a repeat, only 2,000 tourists are allowed to visit each year.

In contrast, Gros Morne National Park, Newfoundland, would love to take your tourist dollars and claims to be one of just two places on Earth where you can step onto mantle rock to feel Earth’s ancient history. Travel bloggers even pitch the area as “Middle-earth” because the mantle is the Earth’s middle layer.

Gros Morne is also a UNESCO World Heritage area and represents possibly the most studied mantle sample. Where Macquarie is new, Gros Morne’s tablelands are almost half a billion years old. Yet these provide a large area composed of mantle and oceanic crust. These rocks are easy to see (and spectacular) because they are inhospitable to plant life. Weathered surfaces are red from all the oxidized iron in these rocks, but material that has not been exposed to the air is usually dark green, indicating mantle rocks like olivine.

Gros Morne National Park’s tablelands are part of the first place on Earth that mantle rocks were recognized at the surface.

Image credit: Frank Fichtmueller/Shutterstock.com

Any Others?

Although Macquarie Island is unique in being made of mantle that is still being pushed upwards, and Gros Morne claims to be one of only two places for mantle walking, that claim is subject to some dispute. For one thing, some other parts of Newfoundland were formed by the same processes that made Gros Morne’s tablelands.

Moreover, no lesser source than Charles Darwin noted that Saint Peter and Saint Paul’s Archipelago in the South Atlantic is not volcanic, but formed by geological uplift.

The mantle material these islands are partially composed of might allow their four temporary inhabitants to place them in the same class as the more prominent sites. However, at a combined size of 1.5 hectares (3.7 acres), much of which will soon be lost to sea level rise, it’s understandable these islands are often overlooked. Perhaps there are other examples we have not been able to find.

How The Mantle Is Exposed

There is still debate as to how pieces of mantle sometimes rise above the crust.

Macquarie Island and Gros Morne have in common that they formed at plate boundaries. Normally, when plates collide, one is driven under the other and pushed into the mantle. However, there are some exceptions.

When continents come together they can squeeze up the ocean basins that initially lie between them. The oceanic crustal material comes to make up much of the resulting mountain ranges, including famous examples like the Alps and the Himalayas. Sometimes some of the underlying mantle gets crumpled in the process, forming what is known as an ophiolite.

While we wait for a geologist with a talent for rhyme to write a song explaining ophiolite formation to the tune of Taylor Swift’s “Opalite”, we will note that most ophiolites are old, fragmentary, jumbled, and often eroded. It’s hard to claim to be able to walk on the mantle there.

The UNESCO listing, on the other hand, calls Macquarie Island “A near-pristine example of an ophiolite.”

Although Macquarie Island’s unique formation remains in some doubt, it is generally thought that the Pacific and Indo-Australian plates pulled apart, exposing mantle material between them. The plates’ direction then shifted so that they pushed some of the Pacific plate beneath the mantle material. Further changes squeezed some of the trapped mantle upwards. Mostly, this just created a bump on the sea floor, but 300,000-600,000 years ago, the pressure got so intense at this one spot that the island was pushed above the waves.

The process for Gros Morne is thought to have been different, and being so much more ancient, we’re even less certain about how it happened, let alone how it survived in such great shape.

Whether they are truly the only places on Earth where mantle-walking is possible is up for debate, but they’re certainly the best.

Source Link: Is It True There Are Two Places On Earth Where You Can Walk Directly On The Mantle?